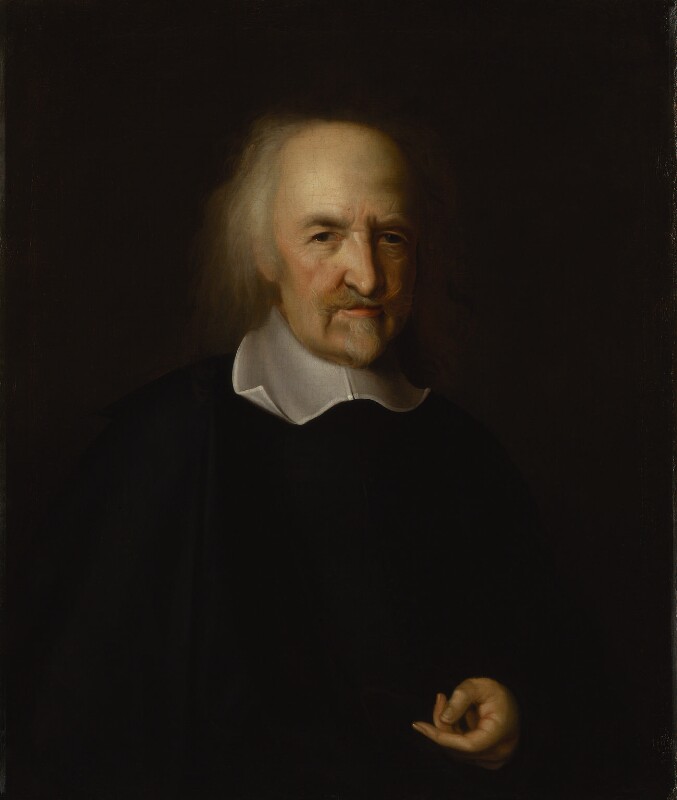

Thomas Hobbes, after John Michael Wright, oil on canvas, based on a work of c.1669-70. National Portrait Gallery, NPG 106. Reproduced under a creative commons license.

Machiavelli was not the only controversial political thinker to have left his mark on The Commonwealth of Oceana. Harrington was also much influenced by Thomas Hobbes. This blogpost will briefly explore Hobbes's influence on the title and structure of Harrington's works. Next month's post will examine Harrington's debt to Hobbes as regards the substance of his argument and his methodological approach.

The precise relationship between Hobbes and Harrington was the subject of speculation in their own time. At first glance they would appear to be on opposite sides of the political divide: the defender of monarchy versus the proponent of commonwealth government. Yet observers saw connections between their ideas. Harrington's critic, Matthew Wren, commented: 'I will not conceal the pleasure I have taken in observing that though Mr. Harrington professes a great Enmity to Mr. Hobs his politiques ... notwithstanding he holds a correspondence with him, and does silently swallow down such Notion as Mr. Hobs hath chewed for him.' ([Matthew Wren], Considerations on Mr Harrington's Common-wealth of Oceana, p. 41). Harrington replied by acknowledging his debt, at least on certain matters:

It is true, I have opposed the Politicks of Mr. Hobbs, to shew him what he taught me, with as much disdain as he opposed those of the greatest Authors, in whose wholesome Fame and Doctrine the good of Mankind being concern'd; my Conscience bears me witnesse, that I have done my duty: Nevertheless in most other things I firmly believe that Mr. Hobbs is, and will in future Ages be accounted, the best Writer, at this day, in the World. (James Harrington, The Prerogative of Popular Government, I, p. 36).

In general, commentary has focused on the second part of this quotation, and in particular on the idea that while Harrington disagreed with Hobbes on political matters, their views on religion were remarkably similar with both insisting that the church should be firmly under state control and treating the political usefulness of religion as more important than its truth. Yet the first part of the quotation - Harrington's claim that he has 'opposed the Politicks of Mr. Hobbs, to shew him what he taught me' - also suggests agreement on certain fundamentals in their political ideas. Harrington often seems to be writing in response to Hobbes, using his ideas as a springboard, so that even where Harrington departs from Hobbes he often uses Hobbesian language and concepts, applying them to different ends.

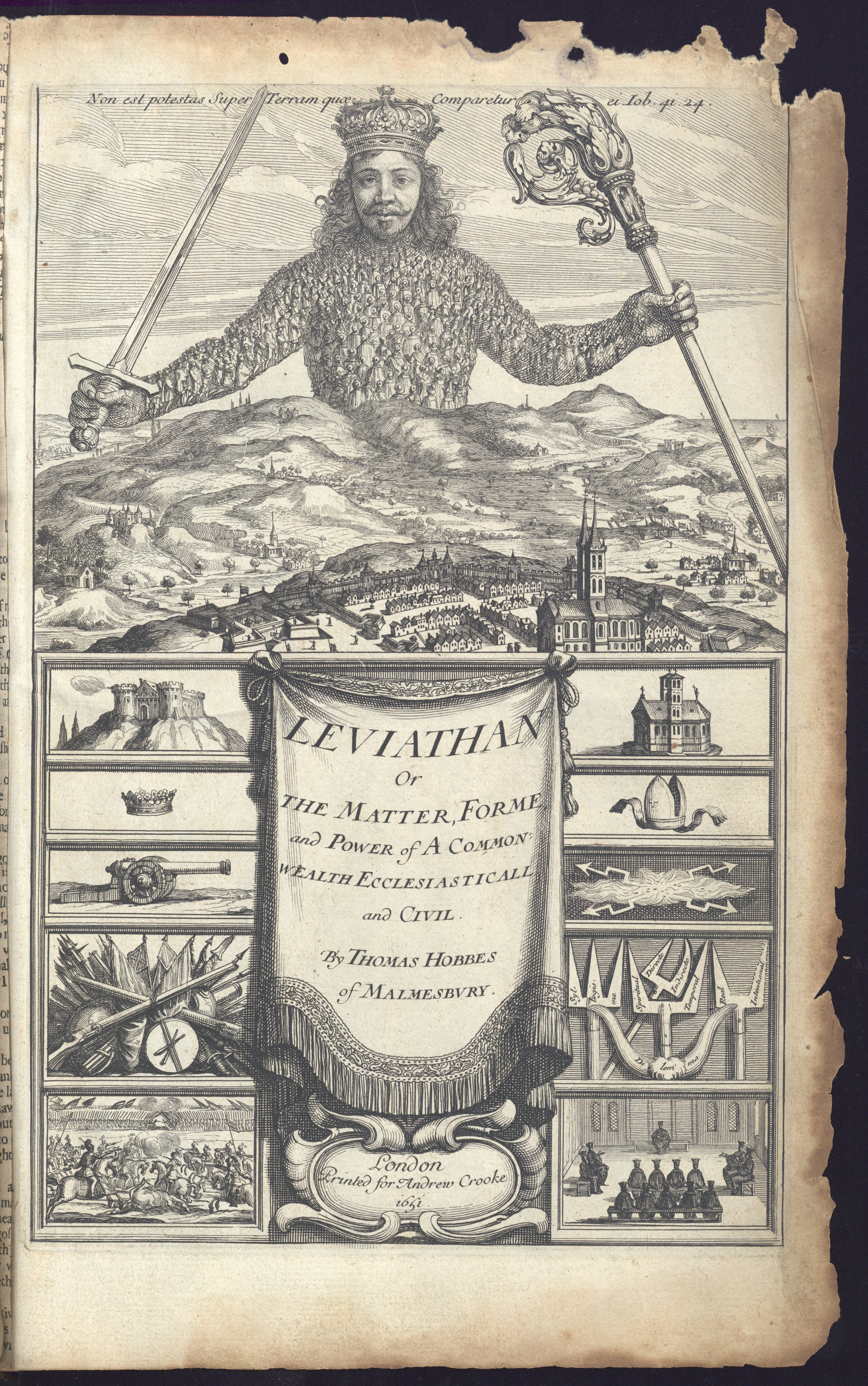

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (London, 1651). Reproduced with permission from the Robinson Library, University of Newcastle. Special Collections, Bainbrigg (BAI 1651 HOB). With thanks to Sam Petty.

This connection is hinted at in the titles of their works. Hobbes called his major work of 1651, Leviathan, alluding to the sea monster described in the Book of Job, the chief characteristic of which was that it could not be constrained by any human power. For Hobbes this was a useful metaphor for his conception of the state. Though it was constituted by the population and designed to secure peace and security, it could not be overthrown by any individual or group among them. Harrington's decision to call his work The Commonwealth of Oceana can be read as a response to Hobbes. Most commentators have seen Harrington's adoption of the term 'commonwealth' as a reflection of his republicanism. Yet he may also have been alluding to Hobbes's own use of that term. On his opening page, Hobbes described the Leviathan as a 'COMMON-WEALTH, or STATE, (in latine CIVITAS)' (Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, ed. Richard Tuck, Cambridge, 1991, p. 9). Similarly, 'Oceana' may not only have referred to England being an island nation. The ocean was the medium in which the Leviathan lives and which, to some extent, restricts and determines its movements and actions. While it may not be constrained by human power, there are other limits on it. It cannot, for example, suddenly start living on land, but must conform to the laws of nature. This fits with aspects of Harrington's argument that will be explored in next month's blogpost.

Not only is there a parallel between the titles adopted by these authors, but connections can also be drawn between the structure and form of their works. The frontispiece to Hobbes's text embodies its entire argument. The Leviathan appears at the top of the image rising up out of the sea. In his right hand he holds a sword - the symbol of civil power - and in his left he holds a crozier - the symbol of ecclesiastical power. This literally reflects Hobbes's argument that both powers should be held by the state. The bottom half of the frontispiece is divided into three columns. The left hand one, beneath the sword, depicts various aspects of the state's temporal power. That on the right, beneath the crozier, depicts aspects of ecclesiastical power. Two of Harrington's works refer in different ways to this frontispiece.

The Prerogative of Popular Government appeared in 1658. It is the work from which Harrington's comment on his debt to Hobbes, quoted above, comes; and it is the work in which Harrington engages most directly with Hobbes's ideas. Given this, it is perhaps not surprising that the structure of the work can be read as echoing the frontispiece to Leviathan. The work is divided into two books. The first, like Hobbes's left hand column, deals with political or civil affairs. The second corresponds to his right hand column in focusing on religious or ecclesiastical matters. And, just like Hobbes's frontispiece, together they make a complete whole. However, while echoing Hobbes's structure, the thrust of Harrington's argument is at odds with that of Hobbes. Where Hobbes had insisted that civil and ecclesiastical powers should be held by a unified state, Harrington argues that both should be organised democratically. Moreover, Harrington cleverly uses Hobbes's arguments to make this point. The second book of The Prerogative defends Hobbes's account of the early church, which emphasised the importance of election by the people in the process of ordaining ministers, against the objections of the Anglican cleric Henry Hammond. What Harrington appears to be saying is that if Hobbes is right in his interpretation of the early church and on the need for civil and ecclesiastical powers to be held in the same hands, then the people should hold both. This, then, is the 'prerogative of popular government'.

‘The Manner and Use of the Ballot’, taken from The Oceana and other works of James Harrington, ed. John Toland (London, 1737). Private copy. Image by Rachel Hammersley.

The second work that refers to the frontispiece of Leviathan is The Use and Manner of the Ballot, a broadsheet which appeared in 1658/9. Recent research has revealed Hobbes's interest in the use of the visual form to spark the imagination. It has shown how seriously Hobbes took the frontispiece to Leviathan; and has opened up various ways in which that image drew on novel visual techniques to convey the complex relationship between the people, the state, and its functions. Harrington was equally concerned with the problem of conveying complex political ideas in an accessible form and he too experimented with visual images to address this issue. From as early as 1656, Harrington had been concerned that the complex balloting procedure in Oceana was difficult for his readers to comprehend. By the beginning of 1659 this had become a major issue. This was because, as he explained in Brief Directions published just a few months earlier, the use of the ballot was difficult to convey in written form. It would, he believed, be much easier for an audience to understand if they were able to experience it in practice. While this was not immediately possible, presenting the ballot in visual form offered an intermediate solution. The Use and Manner of the Ballot consisted of a detailed annotated illustration of the ballot which was accompanied by a commentary describing the balloting process. As Harrington explained at the beginning of the commentary: 'I shall endeavour by this figure to demonstrate the manner of the Venetian ballot (a thing as difficult in discourse or writing, as facile in practice)'. Though the image remained static, Harrington clearly believed that it would allow his audience to envisage how the ballot would operate, thereby convincing them that what might seem on paper like a complex and cumbersome process could be performed quickly and efficiently. (For an animation of this image produced in conjunction with my colleagues at Animating Texts at Newcastle University see: https://research.ncl.ac.uk/atnu/projects/earlymodernballot/#d.en.870683)

Frontispiece from The Oceana and other works of James Harrington. Image by Rachel Hammersley

While this was the only image that Harrington produced, it was not the only one to be associated with his writings. When John Toland produced an edition of Harrington's works at the end of the seventeenth century, he prefaced it with an elaborate frontispiece, which cost him £30 of his own money. Just like the frontispiece to Leviathan, Toland's image embodied the argument of Harrington's works (as interpreted by Toland) in visual form. It could, therefore, be read as a final response to Hobbes.