On Friday 11 December I attended a convivial and inspiring online workshop entitled 'Revolutionary Translations; Translators as Revolutionaries'. It was organised by the team behind the AHRC-funded project Radical Translations: The Transfer of Revolutionary Culture between Britain, France and Italy (1789-1815) - Dr Sanja Perovic, Dr Rosa Mucignat, Dr Brecht Deseure and Dr Niccolo Valmori (all based at King's College London) and Dr Erica Mannucci from the University of Milan-Bicocca. Some of the themes we discussed link to ideas I have been exploring in this blog, so it seemed appropriate to share my reflections on the workshop here.

Since the project is explicitly concerned with radical translations it is not surprising that the question of what we mean by 'radical' - or what constitutes a radical text or translation - featured in a number of the papers. Setting aside broader debates about the meaning of the term, some texts might be deemed radical on account of their subject matter or the context in which they were produced. One such text is Jean-Gervais Labène's De l'éducation dans les grandes républiques, which features on the project database. Here, the aim of the translation - which in this case was by Angelica Bazzoni - is to make that radical text available to a new audience. This practice contributed to the exportation of the French Revolution abroad to Italy and other European countries.

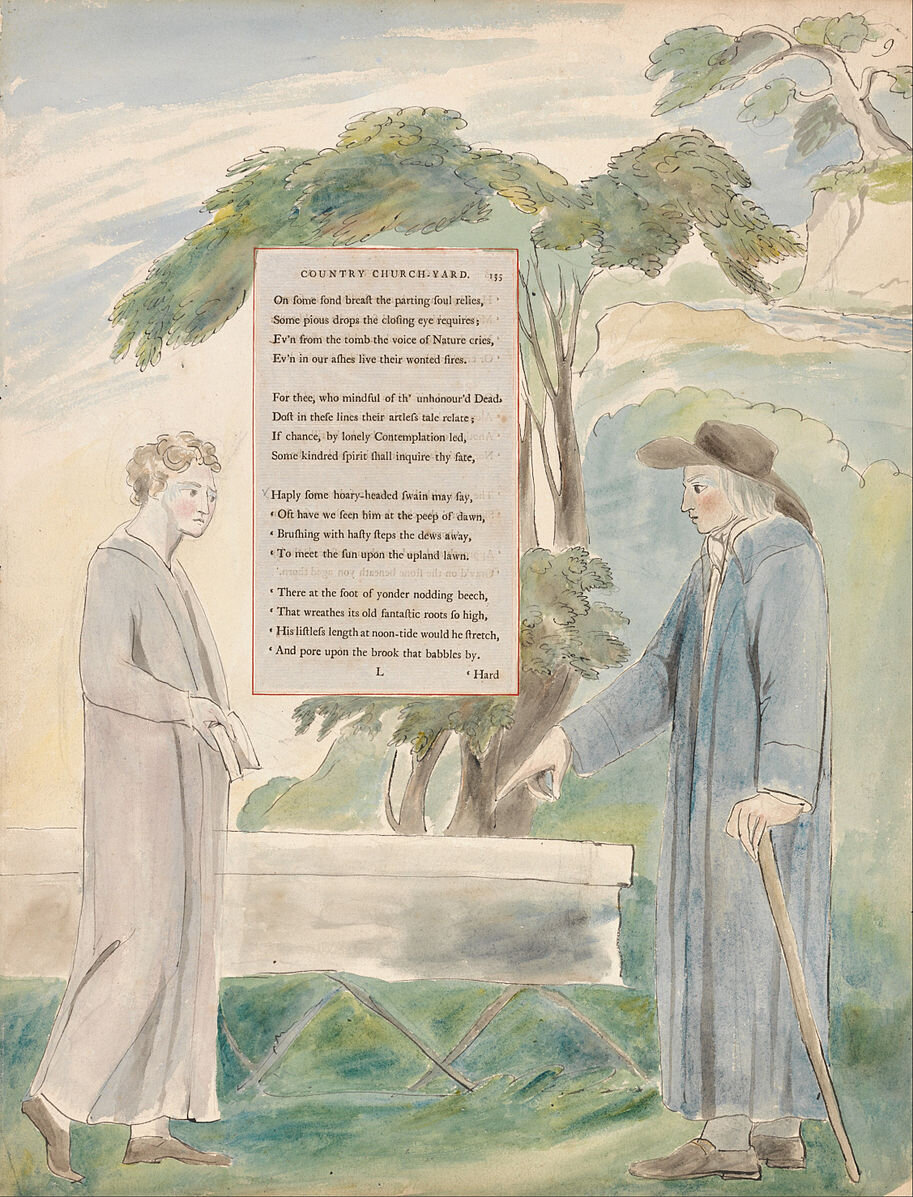

William Blake’s design for Thomas Gray’s poem ‘Elegy Written in a Country Church Yard’. Taken from the Google Art Project via Wikimedia Commons.

There are other cases, though, where the text itself is more neutral, but the translation is radical. A good example of this is the French translation of the English poem Gray's Elegy that was discussed by Catriona Seth. Professor Seth noted that most eighteenth-century translations of this famous English verse were produced by individuals who favoured a moderate or even right-wing position. The 1805 translation, however, was produced by the French revolutionary Marie-Joseph Chénier. His decision to give the date on the title page according to the revolutionary calendar (at a time when this was no longer general practice) can be seen as an indication of his political position and of his aspirations for the translation. As was noted in the discussion at the workshop, there is a potential critique of social hierarchies in the poem, and this was perhaps something that Chénier was hoping to draw out.

Contributors to the discussion also noted that when judging the political radicalism of a translation it is necessary to pay attention to the attitude of the target audience. Rachel Rogers introduced us to the English translation of an account of the overthrow of the French monarchy on 10 August 1792, which was probably the work of the Irish translator Nicholas Madgett on behalf of the English exile Robert Merry. Dr Rogers demonstrated that the translation toned down the radicalism of the event, but noted that the purpose of doing so was to offer a more positive account of it than those that had appeared in London and to encourage sympathy among British readers.

This example highlights a point that was made explicitly by Paolo Conte and Catriona Seth, translations can be a form of activism by another means - a way to continue the fight when physical conflict is no longer safe or advantageous. In his paper, Patrick Leech demonstrated that as well as providing a means to continue the fight after the French Revolution, translation was already being used under the ancien régime to raise revolutionary ideas. The Baron d'Holbach translated key English texts to advance his agenda of spreading radical ideas such as anti-clericalism and materialism.

A second theme that cropped up repeatedly was the importance of form to the meaning of translations and the dissemination of ideas. This was central to my own paper in which I reflected on the importance of both the literary and physical form of translations, and highlighted examples among English republican texts where either the genre or the physical form of the translation was different from the original. Changes in physical form are not uncommon, but I was surprised by how many examples of changes in literary form were referenced in other papers. Professor Seth noted that many of the early translations of Gray's Elegy transformed the English verse into French prose. More surprisingly, Michael Schreiber's fascinating paper on the translations of French legal texts prompted the observation that there was a translation of the Civil Code into Latin verse and this led to reflection on the impact of such a change on the content and syntax of the translation. Both Professor Schreiber and David Armando referred to examples of dual translations where the original text and translation appeared side by side. In some cases this was a way of demonstrating the quality of the translation, but in the case of French legislation, Professor Schreiber argued, it was designed to draw attention to the original French text.

More common is the kind of shift that occurred in the case of the translation analysed by Rachel Rogers. The French original appeared as a newspaper article, the English translation took the form of a pamphlet. The reverse also occurred with pamphlets being serialised in newspapers. These shifts, while not as dramatic as the move between verse and prose, changed the context in which a piece was read and so could affect the way in which the account was perceived by the audience. For example, by incorporating the translation of James Harrington's A System of Politics into his journal Le Creuset, Jean-Jacques Rutledge was able to present the work in instalments and direct key points to events in France as they unfolded. Patrick Leech emphasised the importance in more general terms of journal literature and newspapers - noting that they included, not just translations, but also reviews and abstracts - which were also crucial to the transmission of ideas from one language to another. Janet Polasky went further - noting that ideas do not just travel via printed texts, but also via personal correspondence, conversation and even rumour.

The cover of the Hollis edition of Algernon Sidney’s Discourses Concerning Government, HOU F *EC75.H7267 Zz751s Lobby IV.4.14, Houghton Library, Harvard University. The image here is the figure of liberty. I am grateful to the Houghton Library for giving me permission to include this here and to Dr Mark Somos for his assistance.

Finally, given that an online database is one of the major outputs of the Radical Translations project, it is not surprising that observations regarding digital humanities also loomed large in our discussions. Questions were raised about the limitations and challenges of producing a database. For example, Erica Manucci noted one difficulty faced by the project team had been linking individuals to places when some of those individuals resided in many different locations during their lives. Similarly, Janet Polasky wondered how something like rumour might be incorporated into a database.

Yet there was also an appreciation of the positive benefits that digital humanities can bring. Ryan Heuser's excellent paper on computational semantics epitomised this. He showed how digital analysis can help us to trace changes in the use of words over time. By analysing the words that surround and are associated with keywords in a corpus of texts, it is possible to assess which of those keywords retained a stable meaning over the period and which were transformed. Digital humanities also offers possibilities for the presentation of texts and translations. Many texts (including Gray's Elegy) have been translated multiple times, being constantly improved or updated. It is difficult to reflect this in print editions, but it would be possible to show and compare variants in digital form.

The owl from the cover of the Hollis edition of James Harrington’s The Commonwealth of Oceana, HOU GEN *EC65.H2381 656c (B) Lobby IV.2.18, Houghton Library, Harvard University. I am grateful to the Houghton Library for giving me permission to include this here and to Dr Mark Somos for his assistance.

In her concluding remarks, Dr Perovic made a comment that draws all three of my points together. She said the team had reflected on placing a liberty bonnet next to passages or sections of text that might be deemed radical. This immediately brought to my mind Thomas Hollis's Library of Liberty, which I have mentioned in a previous blogpost. Hollis had special tools designed by Giovanni Cipriani that he used to emboss little gold symbols onto the bindings of texts to provide a short-hand message on the content. The liberty bonnet was one of these, which was employed to identify those works that commended liberty. My favourite example, however, is the owl, which could be placed right way up, to indicate that the work contained wise ideas, or upside down, to suggest the opposite.