The workshops for our Experiencing Political Texts project have been hugely interesting, thought provoking, often inspirational. Yet they also seem to have been cursed. After being evacuated due to a gas leak on the second day of Workshop 1, and having to rearrange one day of Workshop 2 at short notice due to an extra UCU strike day being announced at the last minute, I had foolishly hoped that the rule of three would not apply. But less than a week ahead of Workshop 3, I tested positive for Covid. Several days of manic planning ensued to try to ensure that I would be able to lead the workshop remotely. In the end, I tested negative on the morning of the 11th September and we were able to go ahead as originally planned.

I am very glad this was the case because I not only learnt a great deal from the presentations, but also enjoyed a number of fruitful conversations with participants which would not have been possible if I had been operating entirely via Zoom. One of the benefits of the workshop was coming away with an understanding of the range of digital tools that are now available to researchers. Giles Bergel and Yann Ryan described digital techniques that make it possible to quickly detect illustrations in large text collections; to easily analyse the layout of a page; to identify examples of text reuse in different works; and to analyse language so as to track shifts in meaning over time. We also heard about Jenny Orr's project to map and visualise the correspondence networks of David Bailie Warden and Ruth Ahnert's Tudor Networks of Power project that visualises networks derived from the vast State Papers Online collection. As Yann Ryan noted, one of the next steps for the digital humanities is to combine these techniques so that, for example, it would be possible to link linguistic change to particular networks of printers, or to assess the use of visual elements in different textual genres.

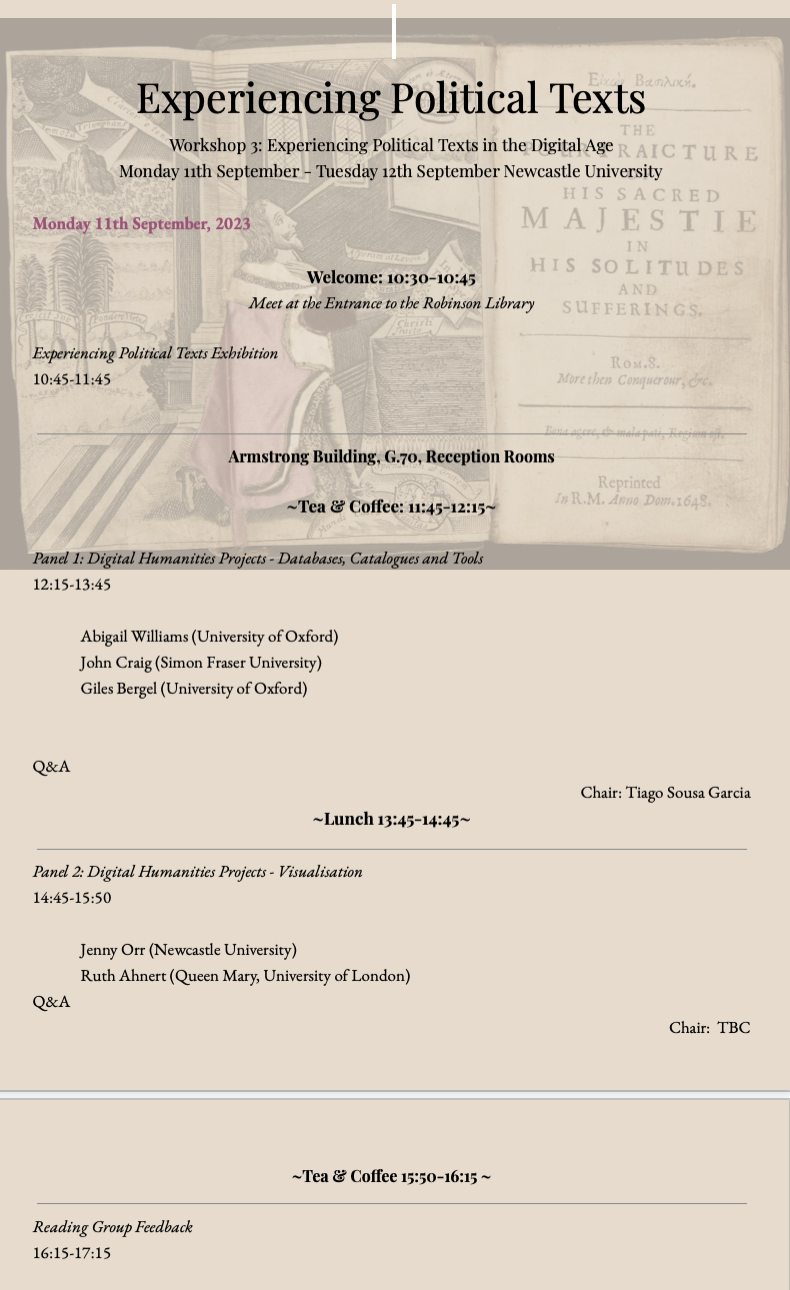

Experiencing Political Texts exhibition, Philip Robinson Library, June to September 2023. Workshop 3 began with a visit to this exhibition. Image Rachel Hammersley

Hearing about these techniques was very inspiring, but I could not help feeling somewhat overwhelmed. This feeling was reinforced by listening to Abigail Williams describe the wonderful Digital Miscellanies project that she worked on between 2010 and 2017 and John Craig present his database of books purchased by English parishes between 1553 and 1642. Both reflected on the fact that they did not necessarily know, when they began designing their database, the questions they would want to ask later on, still less what others using the resource might want to get out of it. Paul Gooding highlighted a related point in his presentation, that when we use massive collections of digital texts like Early English Books Online (EEBO), Eighteenth-Century Collections Online (ECCO), and the Burney Collection of British Newspapers, it is not always immediately evident to us what might be missing, or what contextual information we need in order to make best use of the material.

Fortunately, contributors offered some solutions to these problems. In the first place, those skilled in digital humanities wisely counselled that aiming at perfection (for example seeking to produce a comprehensive database or a digital tool that could be all things to all people) is a fool’s game. Rather, it is better to be realistic - and explicit - about the aims of a particular database or tool.

Secondly, we were reminded that informing and up-skilling humanities researchers on digital humanities techniques can be done through workshops. The Digital Humanities at Oxford Summer School provides a regular opportunity in this regard. Textual Encoding Initiative (TEI) workshops have also been held annually at Newcastle University for several years, and we are exploring the possibility of offering a one-off workshop as a legacy of the Experiencing Political Texts project that would be open to colleagues at Newcastle and members of our network.

Thinking more broadly, Paul Gooding argued that those engaged in digital humanities projects, should make both their data, and the techniques behind it, open access, and provide apparatus to allow users to understand the provenance and history of the data, the principles of curation, and the details of the technologies involved. In doing this creators would help users to better understand the resources they are engaging with, as well as ensuring that useful resources and technologies can easily be moved to new platforms - even after their creators have moved on.

Experiencing Political Texts cakes provided by Harriet Palin and Katie East to share at the close of the workshop. Image Rachel Hammersley

As well as increasing my knowledge of digital tools, the workshop also offered various new insights on themes we have explored elsewhere in our Experiencing Political Texts project. In the first place, it reinforced the idea that how a text is experienced depends on more than just the words. Giles Bergel summarised this very effectively in his assertion that 'authors write texts, but printers make books'. This draws out the importance of materiality, a point that Giles further emphasised by pointing out that, contrary to the impression given by some digital collections of texts, books are not experienced single page by single page - but rather opening by opening with two pages designed to be read alongside each other. In a world in which our encounter with early modern texts is increasingly via screen, it is important that we remember this fact. The assertion also serves to remind us of another observation from earlier workshops: that authors are only one element in the production of a book. Editors, printers - and other workers within a print shop, booksellers, hawkers, translators, reviewers, and even readers themselves, also play a role in the presentation and interpretation of a work, and we overlook their contributions at our peril.

A second insight that links back to our earlier discussions, is that we need to be conscious of whose experience of a text we are thinking about or seeking to facilitate or recreate. My instinct has been to favour original editions of texts and, as a historian, to seek to understand - even recreate - the experience of early modern readers. As I noted in my previous blogpost, members of our reading group drew my attention to the problems that original editions raise for modern readers. I am therefore now more appreciative of the ways in which older texts can be made accessible to readers today. This might involve adjusting the typeface, page size, or layout; ensuring that a work is freely available (rather than behind a paywall); or providing adequate paratextual material containing crucial contextual information that may not be immediately obvious to a twenty-first-century reader. At our workshop I was challenged further on this, coming to wonder whether my scholarly desire to return to or recreate the experience of original readers of a text is even possible. Current readers of early modern texts (myself included) do not live in the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries and our world view, preconceptions, and attitudes are different from those of the individuals who originally read those texts. The circumstances in which we encounter and read such works is also likely to be different. Reading a broadside or pamphlet in a rare books reading room is a very different experience from catching sight of it while walking around an early modern city or purchasing an unbound copy from a hawker on a street corner.

Of course the positive side to this is that the digital provides new opportunities and possibilities. This is true in terms of accessibility. Digital formats can allow an individual to manipulate a text, so as to make it easier for those with visual impairments or dexterity issues to read what otherwise would not be available to them. Digital copies also obviate the need to travel to distant libraries to view a text, removing barriers of mobility and cost. Moreover, the digital makes it possible to produce a multi-layered version of a text in which a reader might toggle between a facsimile of the original page and a clearer modern typeface, or where footnotes containing contextual information can be turned on or off at the click of a mouse. Furthermore, the digital is also starting to make it possible for us to experience texts in completely new ways. For example, it is now possible to take a diachronic view of a ballad, revealing how verses were added or removed over time. Similarly, digital technology can enable us to see variations between different editions of a text at a glance or can allow us to visualise networks that were previously obscured.

In the end, then, I left our final workshop in a positive mood. While we might not foresee all the possibilities when embarking on a project - or even be able to do all the things we want to - the development of the digital humanities is helping us to make texts and data accessible to a wider range of audiences, prompting us to ask new questions, and enabling us to make new connections. What we need as we move forward is to continue to provide opportunities for conversations between humanities researchers and those with technical expertise in digital technology.