Earlier this year the well-known Greek economist and member of the Greek Parliament Yanis Varoufakis published a book entitled Another Now: Dispatches from an Alternative Present. The purpose of the book is to set out the key features of a 'fair and equal' society, or to present the case for - and a vision of - a society based on democratic socialism. Keen as I am to see this ambition made into a reality, what struck me on reading Varoufakis's trailer for the book in The Guardian was less its content than its form or structure. Instead of setting out his argument in a conventional, factual, way - presenting key principles and justifying them - Varoufakis has adopted a fictional format, what he describes as 'political science fiction'. He presents his case, or as he puts it 'narrate(s) the story', via three characters: Iris, a Marxist-feminist; Eva, a libertarian ex-banker; and Costa, a maverick technologist.

Several of the techniques that Varoufakis employs, including his blending of fact and fiction, are reminiscent of the literary devices used by early modern authors of political texts, which are the focus of my current research project. Varoufakis's book can be used as a springboard for thinking about the value of such devices, the role that they played in specific texts in the past, and the use they might have today.

The Occupy Movement forms the basis for the transformations that take place in the ‘Other Now’. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

At the heart of Another Now is the idea of an imagined alternative society, which we could attain if only we make changes in our present (which is of course what Varoufakis is hoping to make us do by writing his book). While trying to develop a highly complex computer program Costa inadvertently finds a wormhole that gives him access to an alternative universe and the means to communicate with his alter-ego, whom he calls Kosti, who lives in that world. By sending messages back and forth through the wormhole, Costa learns that up until the banking crash of 2008, Kosti's life - and the world in which he lived - were identical to Costa's own. However, after that point this 'Other Now' took a very different direction, with several grassroots organisations using crowd sourcing and people power to dismantle the entire capitalist system. Over the space of several years these groups created a world in which employees are equal shareholders in the companies for which they work; all receiving the same basic pay along with bonuses that are decided upon by their colleagues. Banks no longer exist, instead each citizen has three digital accounts over which (s)he has direct control, subject to certain restrictions: a legacy account into which a sum of money is put at birth; a current account; and a savings account.

The title page of James Harrington’s The Commonwealth of Oceana in The Oceana and Other Works of James Harrington, ed. John Toland (London, 1737). Copy author’s own.

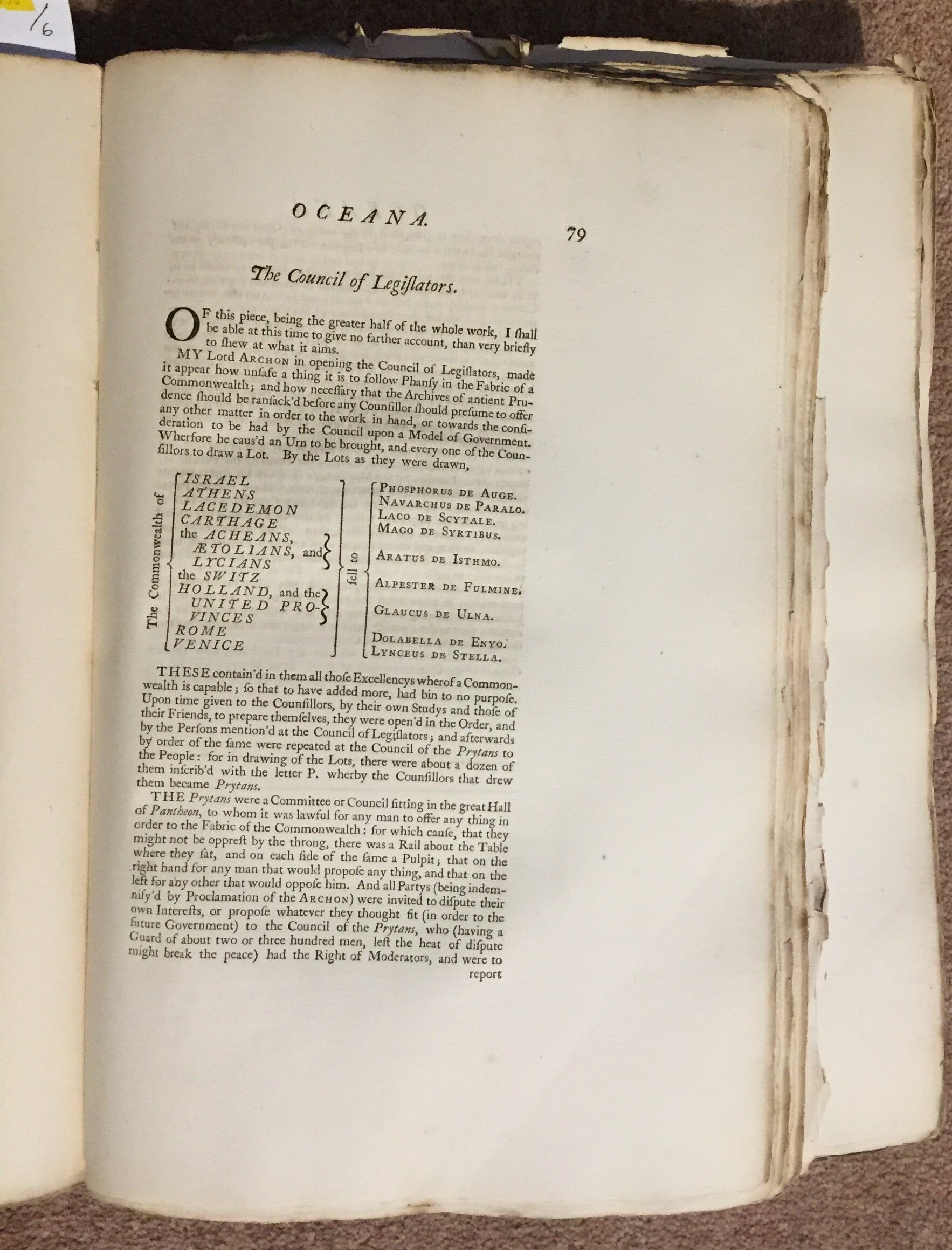

Readers of my last blog post, will perhaps notice the parallel with what I have suggested James Harrington was doing in adopting a semi-utopian format for his major work The Commonwealth of Oceana, which appeared in 1656. In the first section of that work, called 'The Preliminaries', Harrington set out the principles on which his political theory was built and offered an account of English history from before the Norman Conquest up to April 1653 when Oliver Cromwell dissolved the Rump Parliament, which had ruled as a single chamber following the execution of King Charles I on 30 January 1649. At that point, however, Harrington's account moves from history to fiction. Though written in 1656 he narrates not what actually happened between 1653 and 1656, but rather 'another now'; an alternative reality that could have emerged if different decisions had been taken by Cromwell and those around him. Harrington has the character Olphaus Megaletor (who represents Cromwell as he ought to have been) gather around him a 'Council of Legislators' who research various past commonwealths from ancient Athens and Sparta to Venice and the Dutch Republic, and construct an ideal commonwealth from the best elements of each. That commonwealth is then instituted by Olphaus Megaletor in his position as the Lord Archon. Moreover, like Varoufakis, Harrington also projected his story on into the future to indicate the consequences that would have unfolded if that alternative path had been taken. The Corollary at the end of the work takes the story on into the next century. Olphaus Megaletor has just died, at an impossibly old age, and the commonwealth is flourishing. The population has increased by almost a third and the coffers are so full that the nation had been able to go three years without raising taxes. For Harrington, as for Varoufakis, fiction can be used as a tool to justify, and thereby to bring about, a change of course in the present.

Yet, as both authors seem to recognise, the power of fiction lies not only in deploying the author's imagination, but also in engaging the imagination of the reader. As I suggested in last month's post, Harrington's decisions regarding the form of his major work were also influenced by his understanding of people (especially his fellow countrymen) and how they thought about and engaged with politics: 'The people of this land', he accepted, 'have an aversion from novelties or innovation' and 'are incapable of discourse or reasoning upon government' (James Harrington, The Political Works of James Harrington, ed. J. G. A. Pocock, Cambridge University Press, 1978, p. 751). Yet he was confident that if they were given the opportunity to experience a good constitutional model they would recognise it as such. People might never agree to introduce a new form of government, but if they were able to 'feel the good and taste the sweet of it' they would then 'never agree to abandon it' (Harrington, Political Works, ed. Pocock, pp. 728-9). People were more likely to be convinced by political innovation if they experienced it rather than reading accounts of it and there was also a sense of their having to be led towards doing so. Harrington's book was his attempt to do just that. As an author (rather than a politician or head of state) he was not in a position to implement the system in the real world, but by presenting a fictional account he could provide his readers with the opportunity to 'experience' his model within their imaginations. His hope was that this would convince enough of them to make his 'airy model' a reality.

Varoufakis seems to have a similar attitude to the relationship between politics and fiction for readers as well as authors. Not only is the form of Another Now directed at engaging readers' imaginations by offering an alternative vision of the present and future, but this point is made explicit in the opening pages of the book when Iris gives the diary to the narrator and insists that the 'dispatches' in it should be used 'to open people's eyes to possibilities they are incapable of imagining unaided' (Varoufakis, Another Now, p. 2).

‘The Council of Legislators’ section of The Commonwealth of Oceana.

I have no idea whether Varoufakis has read Oceana. Harrington is not listed in the index to Another Now, but it is perhaps revealing that, just over half way through, there is a reference to what economists call a 'self-revelation mechanism design': arrangements that motivate people to act honestly, 'as in the famous method of dividing a pie between two people, whereby one cuts the pie and the other chooses which they want' (Yanis Varoufakis, Another Now, Bodley Head, 2020, p. 138). Those familiar with Harrington's ideas will immediately recognise this as the story of the two girls dividing a cake that is a well-known feature of Oceana.

In an age of Fake News it often feels as though the malleability of facts is dangerous and that blurring the line between fact and fiction will further dupe the public. However, works like Another Now and Oceana remind us that these techniques can also be productive and can be used to reinvigorate, rather than to undermine, the public good. Perhaps, in this brave new world, fiction is one of the most powerful political weapons we have at our disposal.