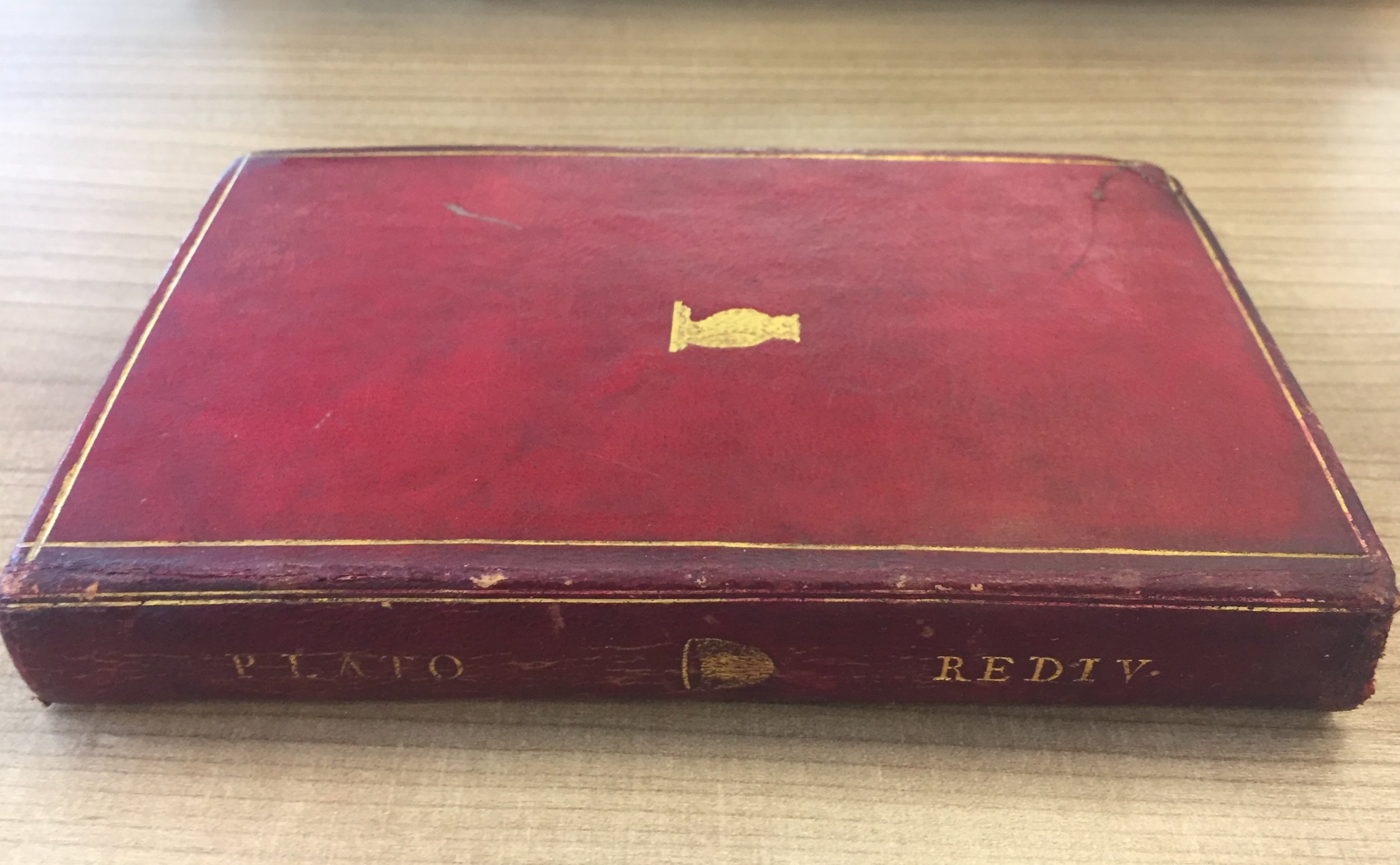

An example of the smoke printed symbol of the pilius or liberty cap taken from Henry Neville, Plato Redivivus, or a dialogue concerning government (London, 1763). This copy, which was donated by Hollis to the Advocates Library in Edinburgh, is now held at the National Library of Scotland: ([Ad]. 7/1.8). It is reproduced here under a Creative Commons License with permission from the Library.

In last month's blogpost I noted that social media platforms have now taken over as the dominant source of news and political information for younger citizens in the UK. One of the main concerns about this shift in news consumption habits is the notion that such platforms tend to generate echo chambers. This results in individuals rarely being confronted by - and therefore required to engage with - views that differ significantly from their own. It can produce a polarisation of positions and a tendency to demonise - rather than seeking to understand - alternative viewpoints. The political dissemination campaigns of the late eighteenth century that were the focus of my last blogpost could be seen as leading to a similar outcome, with campaigners voicing particular viewpoints (such as the benefits of political reform), and dismissing alternative views. Yet in the case of Thomas Hollis, the picture is more complex.

I have touched on Hollis and his campaign several times in previous blogposts, so will not go into great detail here. Suffice to say that he sent a huge number of books to university and public libraries in Britain, continental Europe, and North America. Harvard College in Massachusetts was the recipient of the largest collection of donations, with around 3,000 volumes being sent over several years. Part of Hollis's aim in sending works to university libraries was to influence the education of the rising generation.

An example of the embossed symbol of the wise owl again taken from the National Library of Scotland’s copy of Neville’s Plato Redivivus: ([Ad].7/1.8). Reproduced under a Creative Commons License with permission from the Library.

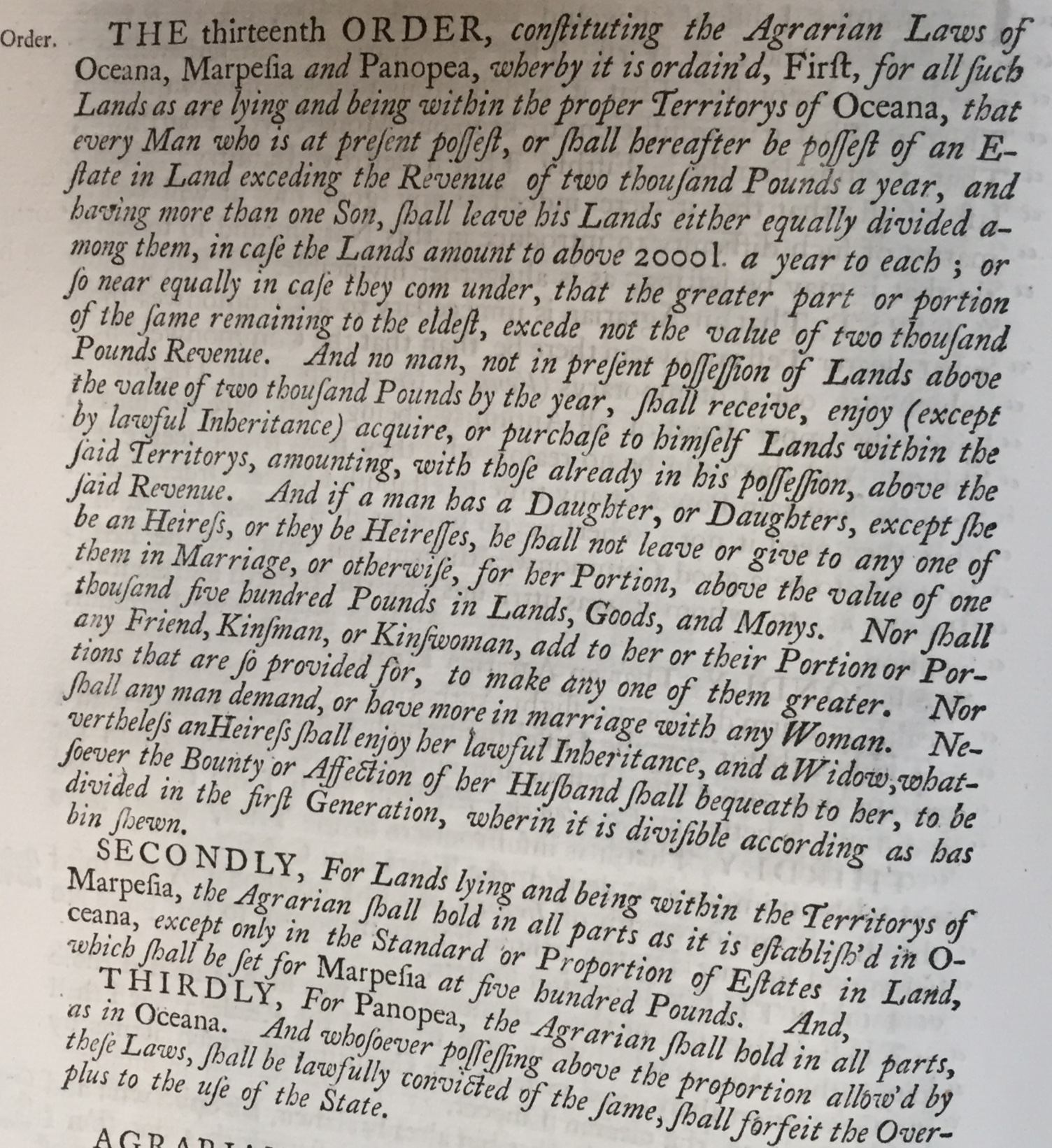

As well as sending the works free of charge, Hollis also manipulated the physical appearance of the volumes he sent in order to shape how they were read and understood. One technique he deployed was to add symbols or emblematic tools to the works (either smoke printed into the text or embossed onto the binding) which served as a shorthand for the content. A pilius or liberty bonnet indicated that the work advocated liberty, a sword was associated with the right to overthrow tyrants, the cock symbolised alertness or vigilance, and an owl showed that the work was wise (unless it appeared upside down in which case it had the opposite meaning). More details on the emblematic tools Hollis used are provided in William Bond's lecture, 'Thomas Hollis: His Bookbinders and Book binding', which can be accessed here.

Another method Hollis used was to add handwritten comments to the texts expressing his views on them or pointing readers towards related works in the collection. Most of these comments were specific to the text itself (and I discussed some of these in a previous blogpost) but there were at least three phrases that can be found repeatedly in works that form part of the Harvard collection.

An example of Hollis’s handwritten marginalia. This comes from an edition of John Milton’s Works, ed. Richard Baron (London, 1753). Reproduced with permission from the Harvard Library copy.

One of these is the phrase 'Ut Spargam', which translates roughly as 'that we may scatter them', 'spargo' being the Latin verb meaning to scatter, strew, or sprinkle. Hollis added this phrase by hand to more than twenty of the volumes he sent to Harvard College. For the most part these are works that set out and celebrate the rights and liberties of the people in politics and religion. They include: several works from the French monarchomach tradition, written by Huguenots in the late sixteenth century, opposing absolute monarchy and justifying tyrannicide; several collections of speeches, acts, or declarations by the English parliament of the 1640s during its confrontation with Charles I; English republican texts such as James Harrington's The Commonwealth of Oceana and Catharine Macaulay's History of England; and several works that deal explicitly with the rights of the people, including Benjamin Hoadly's The common rights of subjects, defended, William Petyt's, The antient right of the Commons of England, and a 1658 work called simply The rights of the people. The point of the Latin phrase was presumably to indicate that these works should be disseminated so that people around the world would come to know their rights.

A box commemorating the repeal of the Stamp Act. From the National Museum of American History. Reproduced from Wikimedia Commons under a Creative Commons License.

There were, of course, particular reasons why this message was pertinent to the American colonists in the 1760s (when Hollis sent most of these works to Harvard). This was a period during which the conflict between the colonists and the British government was escalating. The imposition of the Sugar Act in April 1764 and of the Stamp Act in March 1765 had led the colonists to fear that the British were seeking to exploit and oppress them - imposing taxes without according them representation, thereby infringing their rights as British subjects. The second of these acts provoked the Stamp Act Congress in October 1765 - an early example of co-ordinated action on the part of the colonists. Yet despite securing the repeal of the Stamp Act the following year, the exercise of British control continued. The repeal was deliberately accompanied by the Declaratory Act, which asserted Parliament's right to control the colonies. In June 1767 further customs duties were imposed, and the following year British troops moved into Massachusetts, which had been the focus of the colonial protests. It is not difficult to read off from Hollis's gifts to Harvard his attitude towards the crisis and the fact that he saw it as crucial in this context to remind young American citizens of their rights and the threats posed by overbearing power.

The second phrase Hollis adds to multiple volumes is 'Felicity is Freedom and Freedom is Magnanimity'. It appears in seven works, most of which are recognisably republican texts and two of which also bear the 'Ut Spargam' tag (Harrington's Oceana and Macaulay's History). Interestingly it also appears in A short narrative of the horrid massacre, which described the Boston Massacre of 1770 when British troops fired on protestors. A direct connection is, therefore, drawn between the events of mid-seventeenth-century England and recent colonial affairs. In fact there is a third strand to the parallel, since Hollis attributes the phrase 'Felicity is Freedom and Freedom is Magnanimity' to Thucydides. In Book 2 of The History of the Peloponnesian War Thucydides praises the bravery of the Athenians who died in that war, sacrificing themselves for their country, and he urges their successors to follow their example:

For heroes have the whole earth for their tomb; and in lands far from their own,

where the column with its epitaph declares it, there is enshrined in every breast a

record unwritten with no tablet to preserve it, except that of the heart. These take as

your model and, judging happiness to be the fruit of freedom and freedom of

valour, never decline the dangers of war.

(http://classics.mit.edu/Thucydides/pelopwar.2.second.html)

Like the ancient Athenians and the republicans of seventeenth-century England, the American colonists were displaying a spirit of patriotism that led them to put the good of their country ahead of their own personal interests. The 'Felicity is Freedom' tag endorsed their willingness to fight - even to the death - to defend their rights.

Yet Hollis's strategy was not simply to present his readers with one side of the story. One of the works to which he added the phrase 'Ut Spargam' was Henry Sacheverell's account of his trial. Sacheverell was an Anglican clergyman and popular preacher. In a sermon delivered in November 1709, which he subsequently printed illegally, he attacked Catholics and Protestant Dissenters, comparing the Gunpowder Plot to the execution of Charles I. At his trial, which opened in February 1710 and was accompanied by rioting, Sacheverell was found guilty. As a strong advocate of the Dissenting cause, Hollis will not have shared Sacheverell's views and the parallel drawn between Catholics and Dissenters will have been an affront to Hollis's staunch anti-Catholicism. Yet he still believed that Sacheverell's own account of his trial should be widely disseminated.

Moreover, the plot thickens further if we draw into the discussion Hollis's third repeatedly used inscription: 'Floreat Libertas, Pereat Tyrannis'. The words themselves celebrate the triumph of liberty over tyranny. Yet the works to which Hollis added these words were produced not by advocates of liberty, but by their tyrannical opponents. They include: the collected works of Charles I and his account of his trial; the Letters and dispatches of Charles's close advisor the Earl of Strafford who was executed by Parliament in 1641; and The free-holders grand inquest by the divine right theorist Robert Filmer. It is no doubt significant that while he strongly opposed the arguments reflected in these works, Hollis did not hide them from the Harvard students, but deliberately sent them copies, alerting them by his handwritten inscription that these works contained the arguments of tyrants. Hollis's position seems to have been that it was not sufficient for the colonists to be educated on their rights, they also needed to have a clear picture of what tyranny looked like so that they could recognise it and act quickly when it was imposed against them.

Underlying these decisions by Hollis we can perhaps glimpse the hand of the man he described as 'the divine Milton' (Memoirs of Thomas Hollis, Esq., ed. Francis Blackburne. London, 1780, pp. 60 and 93). In Areopagitica (1644) John Milton argued against the censorship of books, drawing a contrast between the food of the body and that of the mind:

Bad meats will scarce breed good nourishment in

John Milton in the ‘Temple of British Worthies’ at Stowe in Buckinghamshire. Image by Rachel Hammersley

the healthiest concoction; but herein the

difference is of bad books, that they to a discreet

and judicious Reader serve in many respects to

discover, to confute, to forewarn, and to illustrate (John

Milton, Areopagitica. London, 1644, p. 11).

Hollis, following Milton, believed that the American colonists needed to engage with and understand tyranny in order to be able to defend their rights and liberties. The same argument holds today. We cannot understand, let alone defend, what is right, if we are not prepared to listen to, and engage with, alternative viewpoints - even those we might find distasteful.