Recent weeks have seen explosive revelations in America regarding the alleged teenage antics thirty years ago of Donald Trump's supreme court nominee Brett Kavanaugh. The allegations of excessive drinking, sexual harassment, and unacceptable behaviour against a young man who would go on to have a notable legal career reminded me of another young lawyer, this time from the seventeenth century, and his reflections on behaviour and morality.

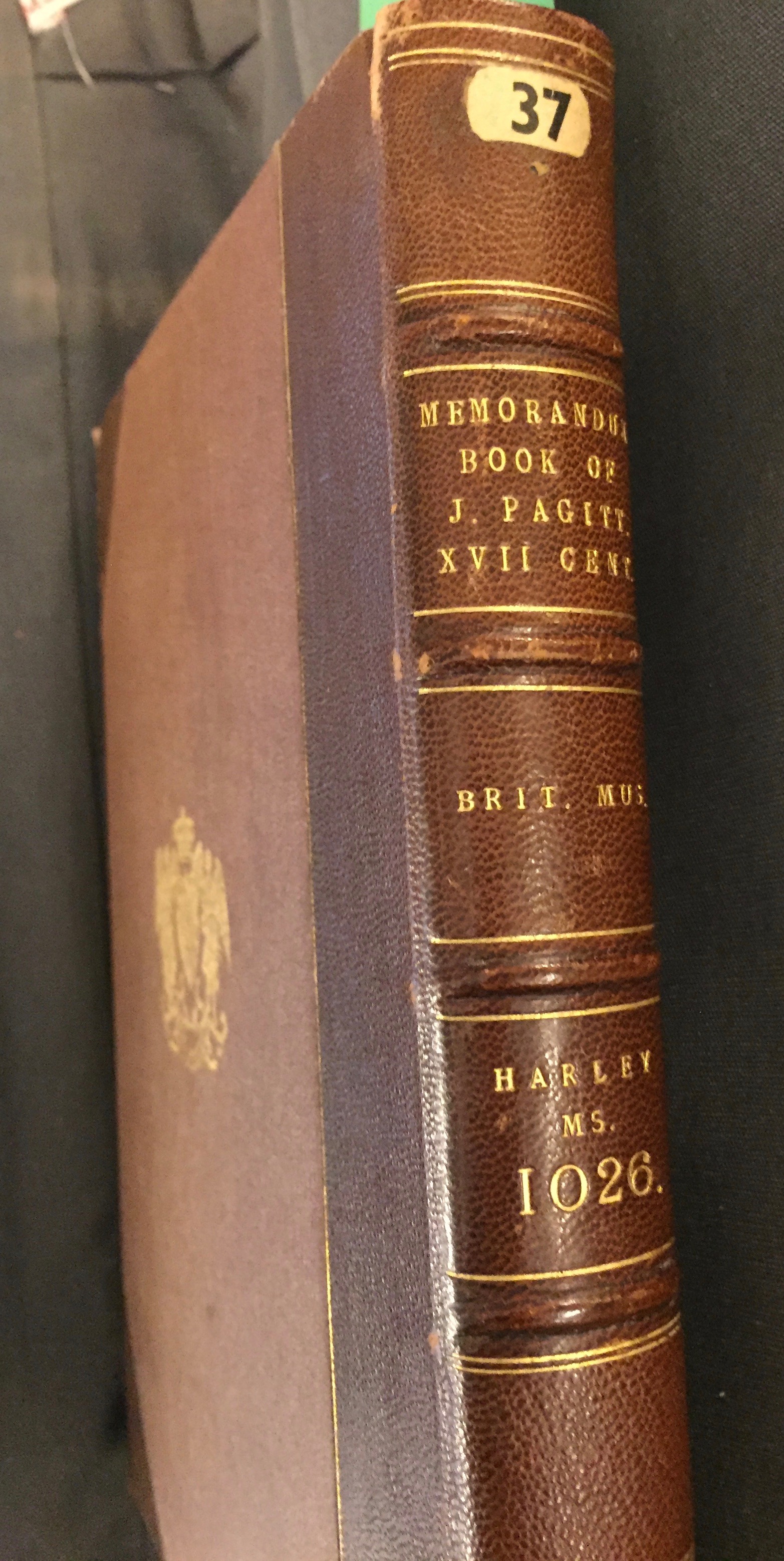

British Library Add MS 4174, Memorandum Book of Justinian Pagitt. Reproduced with permission from the British Library.

That lawyer was Justinian Pagitt (1611/12-1668) who trained at the Middle Temple before going on to a legal and administrative career both during the Interregnum and under Charles II. Pagitt held, among other positions, the office of clerk of the treasury and keeper of writs and records in the court of King's Bench. While official records can be used to trace his public career, we are able to glimpse more intangible aspects of his life thanks to a little known manuscript volume entitled 'The Memorandum Book of J. Pagitt' which is held in the British Library manuscript collection.

I came across this volume because it contains one of a disappointingly small number of references within the British Library's manuscript collection to 'James Harrington'. Moreover, unlike most of the other references thrown up by a search of the catalogue, I was fairly sure that this one did relate to 'my' James Harrington - the author of The Commonwealth of Oceana.

The specific document to which the Harrington reference points is a letter written to Harrington, in early 1634, by Pagitt. The content of the letter, while undistinguished in itself, was of some significance to me in that it filled in gaps in our rather patchy knowledge of Harrington's life prior to the publication of Oceana in 1656. Just how it does so is set out in my forthcoming book. Yet while scanning the volume, I realised that it was of interest beyond what it has to say about Harrington, his early life, and his relations with Pagitt.

The memorandum book consists of entries on a variety of subjects. These are prefaced by a contents page, suggesting that it was intended to be used, probably by its author, since this would make locating a specific entry easier. Several entries are particularly eye-catching.

‘How to avoyd overmuch drinking in Company’ from Pagitt’s Memorandum Book. AD MS. 4174 ff.66-7.

One is entitled 'How to avoyd overmuch drinking in Company'. Over three pages it offers thirteen tips for achieving this goal. It starts by counselling wariness and caution with regard to the company one keeps when drinking. It is, however, realistic in acknowledging that a young man may find himself at a tavern with those who are drinking excessively and that, particularly when toasts are being drunk, it is difficult to avoid participating without appearing churlish. In these circumstances, Pagitt recommends either drinking just a little so as not to end up imbibing too much or feigning illness:

If they urge you to drinke, after a glasse or two faine your self ill & presently go lye down on the bed & then faine to sleepe. Or else clasp yr handkerchief to your nose as if yu bled & presently go dooene stairs & call for a bason of water &c.

While these tactics might seem a little lame, Pagitt did also posit more robust responses:

If these dissioulacons will not serve turne, & if they urge you obstinately tell them though it be their humour to be madd & drunk, yet it is yours to be merry & sober & if they be so resolute to maintain their humour you are as resolute to maintain yours.

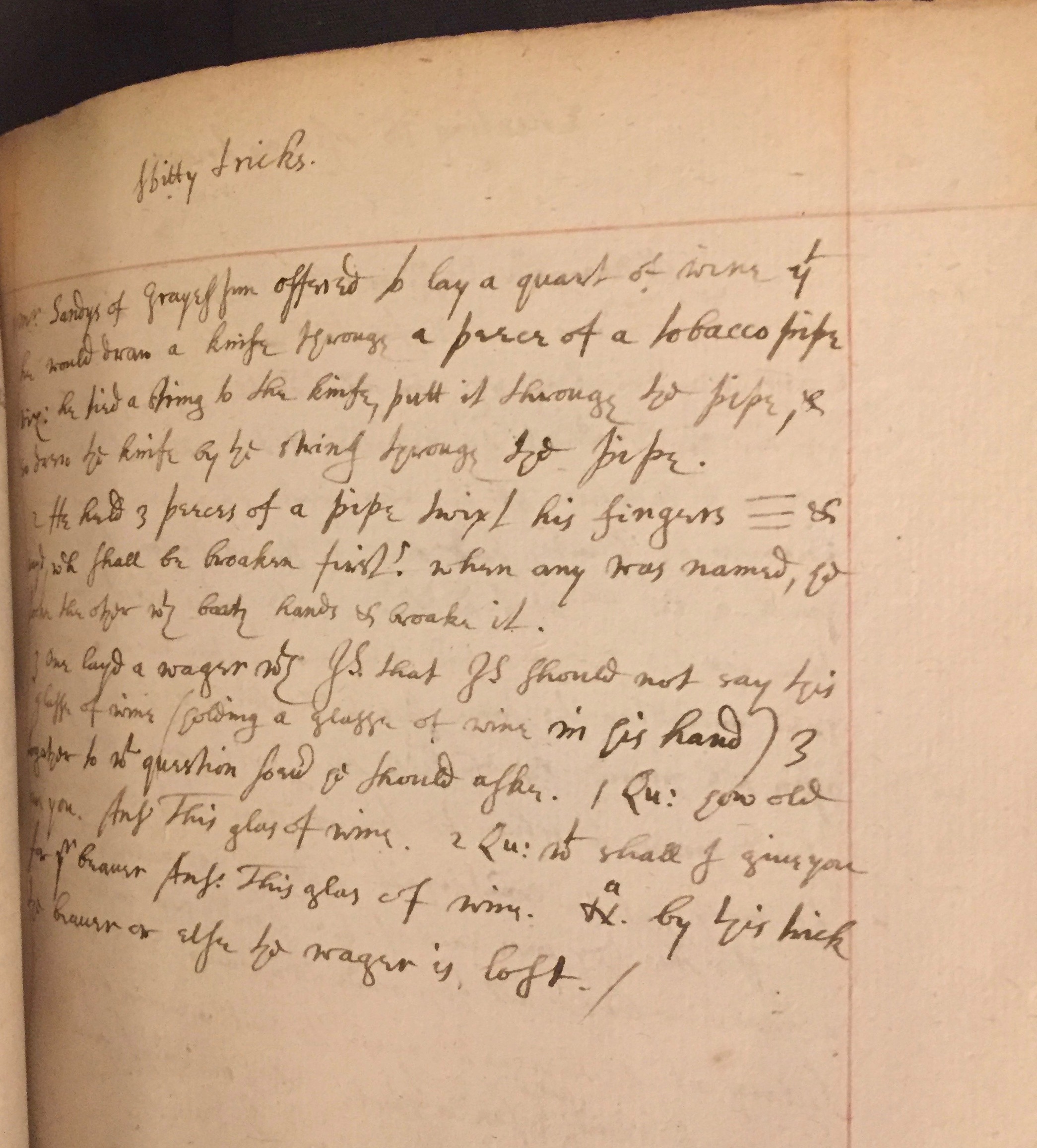

‘Witty Tricks’ from Pagitt’s Memorandum Book.

On another page Pagitt recounts the kinds of 'Witty tricks' that young gentlemen in the seventeenth century played on each other. In the first, 'Mr Sandys of Grayes Inn' bet a quart of wine that he could draw a knife through a tobacco pipe, but instead of cutting through the pipe as his audience presumably expected he tied a piece of string to the knife and pulled both through the pipe. Secondly he held three pieces of pipe in his fingers and asked which would be broken first. When one of the audience suggested a particular pipe he would take one of the others in his hands and break it. Thirdly, he placed a bet that an individual should not say 'this glass of wine' and then asked him two questions, the wording of which forced him into saying 'this glass of wine' and therefore losing the bet.

‘Cum quibus conversando est’ from Pagitt’s Memorandum Book. Add MS. 4174 f.108.

Towards the end of the volume is an entry that provides further insight into Pagitt's moral character. The page is headed 'Cum quibus conversandum est', which translates as 'with whom one ought to consort'. Here Pagitt lists those men who are like him in nature, manners, age and studies and those 'from whome I may receive most benefitt in their consultation'. These appear to have been individuals he saw as positive role models, whose behaviour he might emulate, as much as those from whom he might be able to gain advantage.

Pagitt's Memorandum Book reminds us that the people who produced the sources that we consult as historians were living human beings with similar characteristics and flaws, facing some of the same concerns and temptations that we face. In this light, perhaps Pagitt's reflective attitude regarding his own behaviour remains worthy of emulation today.

(I am grateful to Jeremy Boulton, Katie East, and Sam Petty for assistance with different aspects of this post; to the British Library for permission to reproduce low resolution images of pages from Pagitt's Memorandum Book; and to Louise at Squarespace for technical support).