When writing Republicanism: An Introduction I had to address what happened to republican ideas during the nineteenth century (beyond my usual area of expertise). I chose to focus on France, Britain and the United States. In the process I discovered several interesting nineteenth-century British republicans. I am continuing to investigate some of these characters for other projects. In this blogpost, and some that follow, I will offer brief sketches showcasing these figures and their ideas.

Charles Bradlaugh (1833-1891) was a self-confessed republican who established the National Republican League in 1873. Yet despite not being afraid of controversy and firmly owning his republican views, Bradlaugh's The Impeachment of the House of Brunswick addresses the question of republican politics in an oblique fashion.

Charles Bradlaugh by Sydney Prior Hall. National Portrait Gallery: NPG 2313. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

In his preface to the second edition, Bradlaugh stated explicitly: 'This is not ... a Republican pamphlet' (Charles Bradlaugh, The Impeachment of the House of Brunswick. 4th edition. London, 1874, Preface). What he meant by this is that rather than calling for the abolition of the monarchy, he was simply pointing out that the British monarchy is elective and that the British people have the right to choose different rulers should they wish to do so. He based this argument on legislation from the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It was the Parliament of the English Commonwealth, meeting on 25 April 1660, that gave the Crown to Charles II. Similarly, it was the Convention, meeting with all the authority of Parliament, which on 22 January 1688 took the Crown away from James II and passed over his son the Prince of Wales, bestowing the throne instead on James's Protestant daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange. Furthermore, in various statutes passed under the later Stuarts, the right to accede to the throne was limited, first, to members of the Church of England, and then to the heirs of Princess Sophia of Hanover. Given this history, Bradlaugh insisted, Parliament in his own time had the right, both to deprive a living monarch of the Crown and to treat the heir to the throne as having no claim to the succession.

While Bradlaugh insists that he is not advocating a republican regime, but the replacement of one monarch (or dynasty) by another, his hostility to the Brunswicks is vitriolic. He condemns them for their extravagant expenditure (which he charts in detail), for their hostility to the welfare of the ordinary people, and - more uncomfortably for a twenty-first-century reader - for being foreign. Indeed, what he appears to be advocating is the replacement of the current dynasty - after the death of Queen Victoria - with an English alternative.

Given the history of republican arguments, this position is an interesting one. Bradlaugh is harsh in his condemnation of the Brunswick rulers, but despite admitting his own preference for republican rule, in this work at least he is willing to accept the continuation of the British monarchy under another line.

Alongside his republican writing and campaigning, Bradlaugh was also strongly committed to the issue of land reform. He was involved with the Land Tenure Reform Association, the Land and Labour League and the Commons Protection League and in 1874 he wrote The Land, The People, and The Coming Struggle. Indeed, in the 1870s he presented the Land Question as the key political issue of the day.

James Harrington after Sir Peter Lely, published by William Richardson 1799. National Portrait Gallery: NPG D29116. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

Bradlaugh was by no means the first republican to take an interest in land. James Harrington's argument as to why England was ripe for republican government in the mid-seventeenth century was grounded in his theory that land provides the foundation of political power, and that in order to secure allegiance and stability the form of government should fit the distribution of land within the nation. Harrington believed that changes introduced by the Tudor monarchs had brought a shift in land ownership away from the aristocracy and towards commoners. The civil war, on Harrington's account, adjusted politics to the economic reality, making England ripe for republican or commonwealth government. Later republicans accepted Harrington's understanding of the relationship between the ownership of land and the exercise of political power. By the late eighteenth century, Thomas Spence was using Harrington's argument to put a radical case for the abolition of property rights in England and for a sweeping redistribution of land in order to ensure the subsistence of ordinary citizens.

Bradlaugh too saw land as crucial to political power, and he shared Spence's profound concern for the poor. However, his assessment of the situation in his own time was an inversion of Harrington's original theory. 'The bulk of the land', Bradlaugh insisted, 'is in the hands of comparatively few persons, and these monopolise the House of Lords, and materially control the House of Commons.' (Charles Bradlaugh, The Land, The People and The Coming Struggle, 3rd edition. London, 1877, p. 3). Indeed, Bradlaugh insisted that it was actually the aristocracy, rather than the monarch, that exercised real political authority within the country. This had negative consequences not only for politics, but also for subsistence. It was in the interests of landowners to keep rents high and the wages of agricultural workers low, resulting in poverty and poor living conditions for many people. Moreover, members of the aristocracy liked to keep vast swathes of their land uncultivated for their own recreation - for example in the form of grouse moors. This had resulted in 'The diversion of land in an old country from the purpose it should fulfil - that of providing life for the many' to instead providing pleasure for the few. (Bradlaugh, The Land, The People and The Coming Struggle, p. 13). This, Bradlaugh insisted, was a 'crime'. Similarly he described the game laws as 'a disgrace to civilisation' and as proof of the influence of the landed aristocracy over the legislature, and the negative character of that influence. Bradlaugh's solution was not to abolish property rights, as Spence had advocated, but rather to compel landowners to act more responsibly. As he argued in a speech in the House of Commons in 1888: 'the ownership of land should carry with it the duty of cultivation or utilisation'. The authorities should, therefore, 'compel the possessors of land to use it for the general welfare' (Charles Bradlaugh, 'The Compulsory Cultivation of Waste Lands' in Speeches by Charles Bradlaugh, ed. J. M. Roberts, 2nd edition. London, 1895, p. 116). Most of the land may no longer lie with the commoners, but it should still be used for the public good.

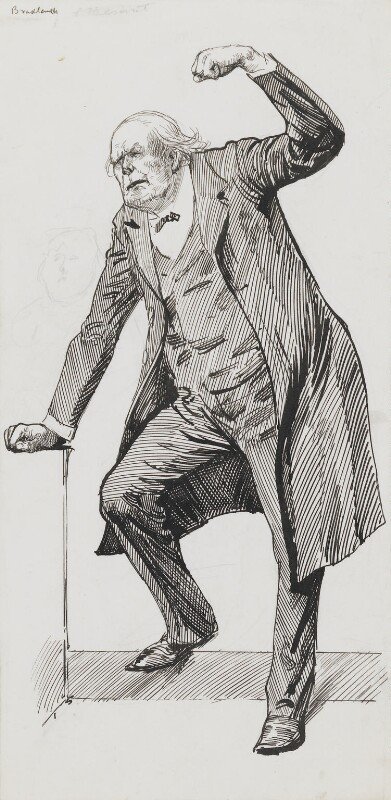

Charles Bradlaugh by Harry Furniss, 1880s-1900s. National Portrait Gallery: NPG 3555. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

As well as being a founder member of the National Republican League and a member of various land reform groups, Bradlaugh also helped to establish the National Secular Society and acted as its president from 1866 to 1871 and again from 1874 to 1890. Bradlaugh was particularly critical of the hypocrisy of the aristocracy who exploited and crushed the poor for their own ends, but then listened to the sermons of bishops, endowed churches, and talked of the importance of saving souls. Bradlaugh was keen to defend both the truth and the morality of secularism. While uncompromising in his atheism, Bradlaugh made reference back to the more subtle freethinking commonwealthmen of the early eighteenth century. In 1877 he established 'The Freethought Publishing Company'. The notion that this may have been an allusion to Anthony Collins's A Discourse of Freethinking of 1713 is reinforced by the fact that Bradlaugh also wrote his Half hours with the freethinkers under the pseudonym Anthony Collins.

Bradlaugh's philosophy, then, involved a critique of the key institutions of the Crown, the Aristocracy, and the Church. While he addressed these issues separately, he was well aware of the connections and overlap between them, and the threat that all three could pose to the people. Throughout his career Bradlaugh worked to uphold the public good, and to place the interests of ordinary people at the heart of politics, he had every claim to be a republican.