A photograph from one of my early modern runs. Image by Rachel Hammersley (2005).

As regular readers of this blog will know, I enjoy running. I particularly enjoy running along the seafront near to my home. Not surprisingly it is a popular place to run and I regularly spot the same people out enjoying their own early morning exercise. One of the characters who always makes me smile is the man my daughter and I call 'Tories Out Man'. For weeks in the run up to the 2024 General Election he would run along the seafront wearing a black tee-shirt emblazoned with the words 'Tories Out' in large white letters. On being offered any sign of encouragement from those running in the opposite direction he would smile, raise a clenched fist and shout 'Tories Out'. As I worked on my paper for the Radical North conference that I reported on last month, it struck me that this man is adopting a twenty-first-century example of the kind of methods that Thomas Spence used more than two hundred years ago to disseminate political messages.

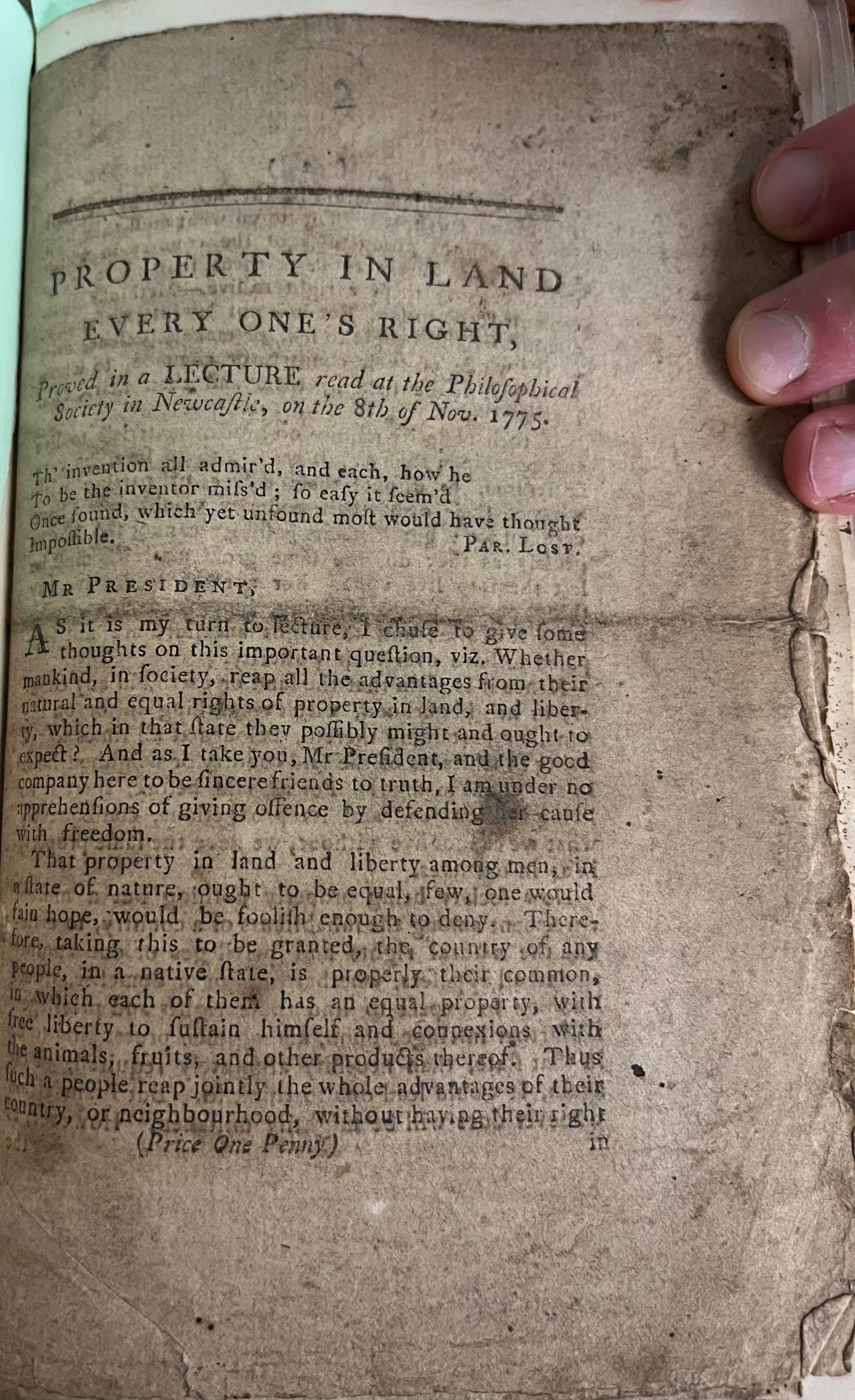

An original copy of Spence’s lecture ‘Property in Land Every One’s Right’ from the Hedley papers at the Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society. Reproduced with permission.

While living in Newcastle in the 1770s Spence came to the conclusion that the oppression and poverty that he saw around him could be eradicated if the land was owned not by individual landowners but collectively by local residents. In a lecture that he delivered to the Newcastle Philosophical Society on 8th November 1775, he set out his vision for how this plan could be enacted. Each parish would form a corporation, composed of all adult males who had been resident within the parish for at least a year. The corporation would take ownership of the land within the parish, renting out portions of it for cultivation by local residents. The rents paid for use of the land would replace taxes, providing revenue to cover central government charges and to fund local facilities and services. Having composed this potentially transformative plan, Spence was keen to share it in the hope of having it implemented. For the rest of his life, he deployed various means of sharing his land plan with as wide a public as possible.

Immediately after delivering his lecture Spence had it printed, incurring the anger of members of the Philosophical Society who did not want to be publicly associated with Spence's ideas. Another printed version appeared under the title 'The Real Rights of Man' in Spence's Pigs' Meat periodical in 1795. Yet Spence was not content with simply reprinting the lecture, in addition he produced multiple versions of the plan in a variety of written forms. He incorporated it into works of utopian fiction in A Supplement to the History of Robinson Crusoe (Newcastle, 1782), 'The Marine Republic' - which appeared in Pigs' Meat in 1794, and Description of Spensonia (London, 1795). Several of these works also made use of dialogue form to address potential objections to the plan. He also presented his ideas in A Letter from Ralph Hodge, to his Cousin Thomas Bull (London, 1795), which adopted the epistolary form and concluded with a series of questions and answers. In addition he produced two model constitutions The Constitution of a Perfect Commonwealth (London, 1798) and The Constitution of Spensonia (London, 1803), and he printed two accounts of trial proceedings against him - The Case of Thomas Spence (London, 1792) and The Important Trial of Thomas Spence (London, 1803) both of which again served as vehicles for him to disseminate his ideas. Presenting his plan in different forms - and especially using genres like utopian fiction and dialogue that engaged the imagination - was a way of reaching as wide an audience as possible.

Nor did Spence limit himself to texts that were designed to be read. He also wrote songs which again conveyed his ideas, but which could be shared in political meetings and gatherings, making them more accessible to those who were unable to read. The songs were to be sung to familiar tunes such as 'Hearts of Oak' and 'Derry Down'. Some were even set to well-known patriotic tunes including 'Rule Britannia' ('The Progress of Liberty', 1793 and 'The Liberty of the Press', 1794) and, most provocatively, 'God Save the King' ('Rights of Man', 1793). This was a deliberately subversive act - in which Spence filled an establishment vessel (the tune of the national anthem) with his own radical content.

One of Spence’s counter-stamped coins. Image taken from Wikimedia Commons.

Spence performed a similar act of subversion with coins. After his move to London he began counter-stamping coins of the realm. In this case the establishment vessel was a coin bearing the image of the King's head and Spence's radical content was the subversive slogan which would be stamped across it. The example illustrated here shows a coin from the reign of George III that has the phrase 'NO LANDLORDS YOU FOOLS SPENCES PLAN FOREVER' obscuring the King's head.

A Spence token celebrating the Rights of Man owned by the author. Image Rachel Hammersley.

Spence also produced coins or tokens of his own which he was said to toss out into the street, so that local people could pick them up for free and then exchange them at his shop for a pamphlet. Again the tokens generally reflected Spence's ideas, such as the one bearing the slogan 'Man over man he made not lord'. They were also explicitly used to advertise his pamphlets. The reverse of the token just described advertises Spence's Pigs' Meat while another, which depicts two men throwing title deeds onto a bonfire, bears the label 'The End of Oppression' which was the title of another of Spence's works. Spence also used tokens to commemorate his own experience of oppression or that of others - such as John Thelwall and George Gordon - or to comment on current affairs.

It was not only via paper and metal that Spence conveyed his ideas. He etched his slogans wherever he could. In 1780 he visited a former miner known as 'Jack the Blaster' who lived in a cave at Marsden Rock on the coast between South Shields and Sunderland. The cave or grotto still exists and currently houses a bar. 'Jack the Blaster' had apparently gone to live at Marsden Rock having not been able to afford the rent on a more conventional home. Spence claimed that this inspired him to chalk the following words above the hearth:

The bar inside Marsden Grotto. Image by Rachel Hammersley (2022).

Ye landlords vile, whose man’s place mar

Come levy rents here if you can,

Your steward and lawyers I defy

And live with all the Rights of Man.

(Thomas Spence, 'The Rights of Man for

Me', in his Pigs Meat (London, 1794-5),

Volume 3, p. 250)

On this basis Spence claimed to have coined the phrase 'the Rights of Man' more than ten years before it became associated with Thomas Paine. Decades later, Spence's followers were said to have chalked Spencean phrases on the walls around London. The Home Secretary reported that "Spence's Plan and full Bellies", and other similar messages, had appeared "on every wall in London" and in 1816 William Cobbett wrote to Henry Hunt saying:

We have all seen for years past written on walls in and near London the words

'Spence's Plan' and I never knew what it meant until ... I received a pamphlet from

Mr. Evans ... detailing the Plan very fully. (Memoirs of Henry Hunt, Esq. London,

1820, p. 381).

I cannot help but think that had custom-printed tee-shirts been available in Spence's time, he would have had one printed with a suitable slogan and would have worn it (and urged others to do so) on the streets of London and his native North East.

For those wondering what happened to 'Tories Out Man' in the aftermath of the election, I am pleased to say that he is still running along the seafront. When we saw him in December he was wearing a new tee-shirt which read 'Tories Outed, 2024'!