The main square in Wolfenbüttel. Photograph by Rachel Hammersley.

Last year I attended a 'Translating Cultures' workshop organised by Gaby Mahlberg and Thomas Munck. I found it so collegial and thought-provoking that I was delighted to be invited to attend the follow-up this October. The occasion did not disappoint. The location is one where early-modern historians instantly feel at home: the beautiful Lower Saxony town of Wolfenbüttel has a remarkably well preserved collection of 17th century houses, complete with mottos carved into the lintels. And the Herzog August Bibliothek (HAB), which hosted our workshop, is a wonderful research library based around the collection put together by Duke August the Younger, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

The Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel. Photograph by Rachel Hammersley.

The HAB and its director, Peter Burschel, and head of scientific programmes, Volker Bauer, were very hospitable hosts, but the positive and stimulating atmosphere also owed much to the excellent conference organisers, Gaby Mahlberg and Thomas Munck, and to the other participants, who without exception delivered thoughtful and engaging papers. Gaby has offered a summary of the workshop here, but I would like to take this opportunity to offer my own reflections on some of the themes that surfaced during the two days. In particular, the papers provided food for thought on three issues that I have been pondering myself recently: language, genre, and materiality.

Given our focus on translation, it is not surprising that several papers touched on the limitations of language and the difficulty sometimes of conveying a particular idea or concept in a foreign language. Lázló Kontler in his paper on the translation of Montesquieu into Hungarian, pointed out that 'parliament' is a difficult word to translate into Hungarian. It ended up being translated as 'word house' which while alluding to the etymology of the word, seemed rather quaint and provoked smiles around the room. Several papers developed this point to suggest that certain ideas or concepts might be easier to express in one language than in another. In his paper on the Book of Job, Asaph Ben-Tov noted that, while this was not (as some in the early-modern period had believed) a Hebrew translation from an Ancient Arabic source, there was nevertheless a sense in which the ideas it contained could be more easily understood in Arabic than in Hebrew. Nor is this just a question of the written word. Jaya Remond in discussing colonial botanical texts, raised the idea that images might themselves be viewed as a language made up of lines and dots, and that a picture might evoke an object much more effectively than could ever be achieved in words. Rachel Foxley went even further in exploring language, translated words, and the power they wield. She looked at the translation of terms from Latin and Greek as a way into thinking about how the language of innovation and revolution developed in seventeenth-century England. She showed that, while the Roman term 'novae res' evoked a sense of innovation that was linked to the restless crowd and to demagoguery, this was set against an Aristotelian understanding of the means by which more gradual change by the authorities might bring about revolution. In this way, ancient languages of innovation were deployed by both sides in the build up to the English Civil War.

Portrait of Aphra Behn by Robert White, after John Riley line engraving, published 1716. National Portrait Gallery, NPG D30183. Reproduced under a creative commons license.

Not only were specific terms or languages felt to be most appropriate for conveying particular concepts or ideas, but the choice of genre may also be important. In her paper on Aphra Behn's translations of French works, Amelia Mills made the fascinating observation that Behn's version of Paul Tallemant's Le Voyage de L'Isle d'Amour not only translated the language from French to English, but also transformed an original prose work interspersed with small sections of verse into a work that was entirely in poetic form. As a group we speculated about Behn's motivations in doing so. Perhaps she viewed poetry as higher form and was using the transformation to show off her skills, or perhaps she felt poetry to be a more appropriate mode of writing for a woman at that time.

Several papers noted the fact that in the early-modern period historical writing was often seen as a good vehicle for the transmission of political ideas. Helmer Helmers described the deliberate efforts of the Dutch government to produce histories of the Dutch Revolt for European dissemination. The state invested more than 40,000 guilders in histories of this key event that were translated into German, French, and Latin. Emanuel van Meteren's history of the Dutch Revolt proved particularly popular going through 111 editions and translations between 1596 and 1647 including no fewer than 74 German versions. Almost as popular were the Italian translations of the historical works of William Robertson, examined by Alessia Castagnino, with more than 50 translations appearing in the early-modern period. In her paper on the 1627 French translation of Francis Bacon's History of the Reign of Henry VII, Myriam-Isabelle Ducrocq delved into the question of why that work should have been of interest to the French at that time, concluding that the reign of Henry VII offered a useful antidote to French absolutism. It held a revealing mirror to Louis XIII in presenting a King who sought to reconcile warring parties and to promote religious concord.

French translation of Algernon Sidney’s Discourses Concerning Government by P. A. Samson. Reproduced from Wikimedia Commons.

Several participants touched on another genre of writings which while not translations in themselves, are closely connected to them - reviews. For Thomas Munck these offer one valuable way of gaining an insight into the 'imagined community of readers' that can prove so elusive to those of us working on the early-modern period. Reviews were presented as particularly useful in this regard as they need not be purely national in focus, and therefore when dealing with translated works may provide insight into transnational communities of readers. Thomas - and Gaby Mahlberg in her paper on German reviews of Algernon Sidney's Discourses - noted that, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries reviews start making comments about the nature and quality of the translations themselves, suggesting an emerging understanding of what was considered a good translation. In my own paper on the reception of James Harrington's ideas in revolutionary France I pointed out that while reviews are not translations, a review in a different language from the original work can perform some of the same functions, not least in providing an account of the argument and key points of the work for a foreign audience and many early-modern reviews included lengthy quotations translated directly from the text, thereby constituting at least a partial translation. Both French and German reviews of Sidney's Discourses Concerning Government that appeared in the early eighteenth century are a good example in this regard. The idea that the basic content of a text could be disseminated without an actual translation appearing was also picked up by Lázló Kontler who noted that Montesquieu's ideas had already been much debated in Hungary long before the first full translation of The Spirit of the Laws appeared in 1833.

Finally, various papers touched on the materiality of texts, including translations, and what texts as physical objects and associated artefacts might reveal about the aims, audience, and reception of texts. William Robertson, Alessia Castagnino explained, deliberately laid out the original text of his history of Scotland so that it could appeal to two distinct groups of readers - on the one hand scholars and on the other a more general, casual public - placing the notes and other scholarly apparatus in such a way that they could be accessed, but did not interfere with the flow of the narrative. The Italian translators, however, eschewed this method, instead producing separate translations for different audiences. Crocchi's 1765 translation was deliberately aimed at government and administrative officials, men of letters and science, whereas Rossi's 1779-80 translation was directed at a wider audience. The absence of illustrations and other supplementary elements ensured that the volume was cheap, costing the same as just 24 eggs, prompting Alessia to joke that Italians could choose between Robertson's history and a very large omelette.

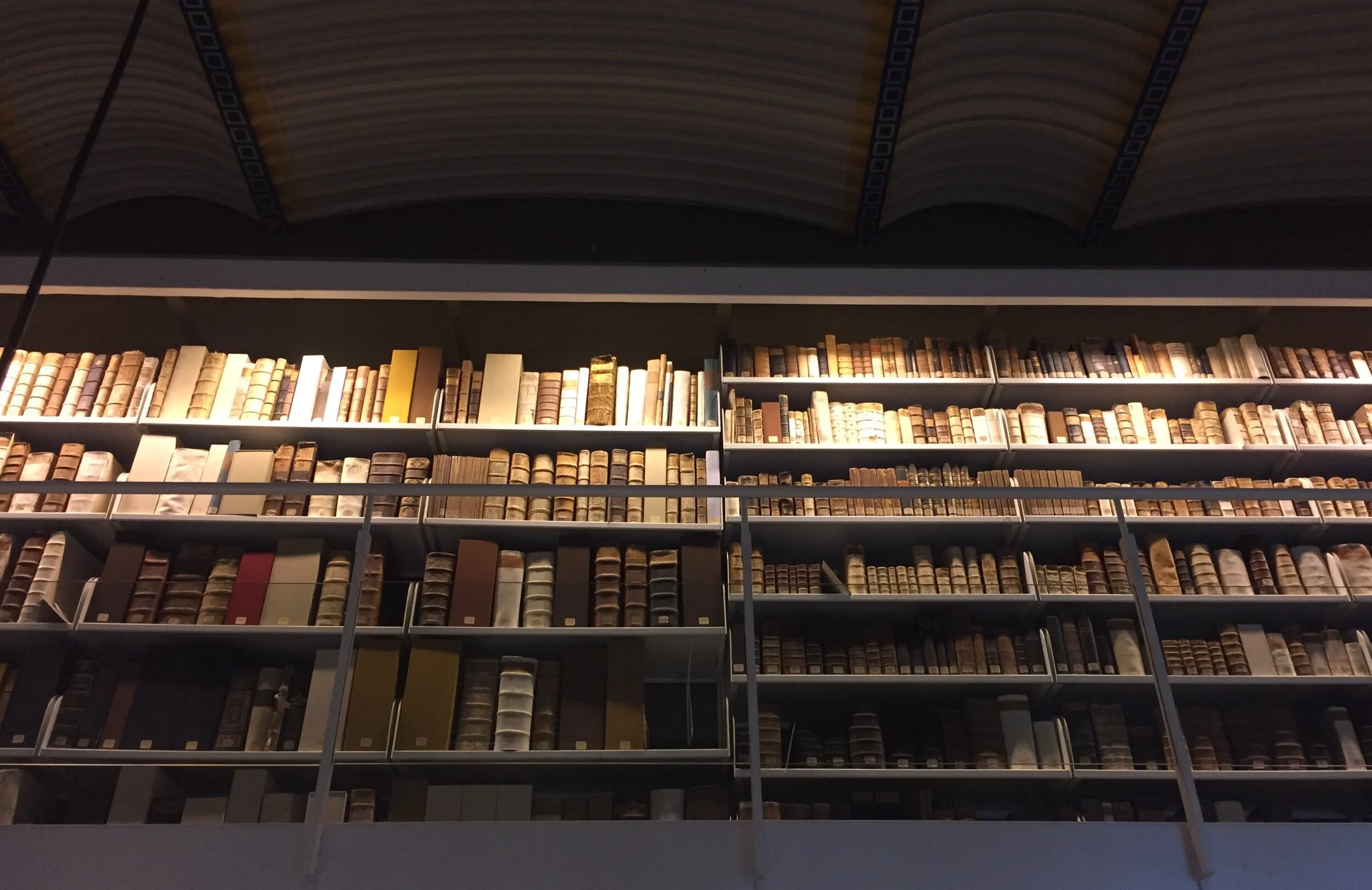

The interior of the Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel. Photograph by Rachel Hammersley

A number of the translations discussed at the workshop were also linked to or associated with other objects. For example, the Collection Magliabechi, put together by Raimondi on behalf of the Medici and discussed by Luisa Simonutti, involved the gathering and production not just of books but also of seeds for the Medici garden. Moreover, the collection includes not just the books themselves, but also some of the original plates that were used to produce the lavish images that adorned them. As far as I am aware, Thomas Hollis did not send seeds from England to Europe or America, but he sent more or less everything else. Moreover, as Mark Somos demonstrated in his paper, Hollis sought to link texts with other texts, and with objects and networks. This is evident from the extensive marginalia that he added to the copies of books he sent to libraries around the globe. As Mark argued, Hollis's aim was to guide his readers through the works, pointing them to related works (sometimes even giving page numbers) and creating a trail for them through republican writings. I was particularly fascinated by the observation that his technical comments on the works of John Milton (an author almost always featured in the donations he sent) often refer to Harrington, suggesting that Hollis wanted his audience to read Milton through the lens of The Commonwealth of Oceana.

It is a sign of a good workshop that it prompts one to ponder new projects and future work. It is testimony to just how good this one was that I left eager to pick up Hollis's trail for myself and to follow his texts across Europe and North America. For now, though, I think I will have to remain content with looking forward to next year's workshop.