October proved to be a busy month for conferences. Just days after having returned from Wolfenbüttel invigorated by discussions around 'Translating Cultures' I was part of a team organising a conference at Newcastle University on the subject of 'Civil Religion from Antiquity to Enlightenment'. Here too there were a number of outstanding papers that stimulated thought and provoked discussion on this fascinating, but understudied topic. The downside of hosting a conference at your own institution is that it is not easy to prevent other commitments from encroaching, so unfortunately I was not able to attend all of the sessions. The following reflections, then, are based on those that I was able to hear.

The biggest questions sparked for me concerned definitions. What do we mean by 'civil religion'? Has it been understood consistently in all times and places? And is civil religion best understood as a tradition, a concept, or an approach?

Ronnie Beiner, author of Civil Religion: A Dialogue in the History of Political Thought (Cambridge, 2010), drew on Rousseau's distinction between civil religion - the subordination of religion to politics - and theocracy - the subordination of politics to religion. In the modern world, Beiner explained, there is a third way of conceptualising the relationship between religion and politics - the idea of complete separation. This is the conception that lies at the heart of the fully secularised polity favoured by liberals, where religion should not play any role at all in the political sphere.

Mark Goldie in his paper 'Civil Religion in Early Modern England' began by acknowledging the distinction between civil religion, theocracy and secularism, but went on to suggest that there is an alternative approach to civil religion which understands it to be deeply embedded within Christian theology rather than constituting a dissolution of it. In Goldie's view, early-modern civil religion was a Christian project. The issue was not Christianity, but Priestianity. Considered in this way civil religion is concerned as much with reformation and a return to the apostolic church as it is with the subordination of religion to politics.

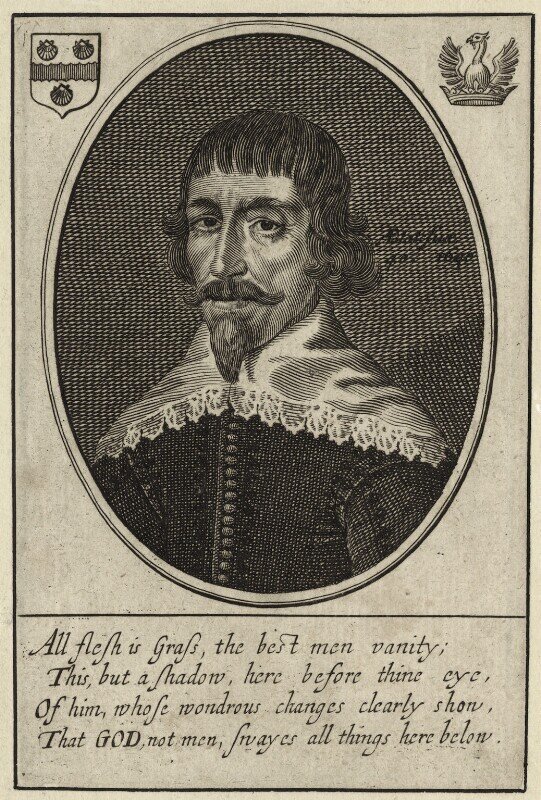

William Prynne after Unknown artist, line engraving. National Portrait Gallery, NPG D26979. Produced under a creative commons license.

Various other speakers flagged up the importance of this approach, particularly in an English context. Esther Counsell showed how Puritans like Alexander Layton and William Prynne saw the reframing of the church on the model of civil religion as the basis for reform. Nor was this understanding of civil religion as a Christian project merely a feature of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In both his paper, and the forthcoming book on which it is based, Ashley Walsh demonstrates the richness and vitality of the idea of a Christian version of civil religion in eighteenth-century Britain.

Yet, in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England there was no single answer to the question of the appropriate relationship between religion and politics. Polly Ha flagged up some of the difficulties faced by the Anglican establishment. In theory it sought to introduce a 'civil' reformation, yet in practice incivility, discord, and dissent soon challenged this ideal, raising difficult questions as to the boundaries of civil and religious jurisdiction. This was a theme picked up by Connor Robinson in 'Reformation, Civil Religion, and the University in Interregnum England', which examined the role of universities, at least in the eyes of some, as vehicles for the implementation of civic reformation. John Coffey outlined the wide variety of attitudes to church-state relations that were being voiced by the 1650s. Presbyterians insisted on religious uniformity and the existence of a national church. Magisterial independents, by contrast, firmly rejected the idea of a national church, but accepted that the magistrate could have authority over national religion and the policing of heretics. Radical independents went further still, repudiating magisterial enforcement of orthodoxy and the policing of heresy. Their position was very close to that of the Godly republicans who called for the complete separation of Church and State. Harringtonian republicans, by contrast, adopted a more moderate position that again supported the idea of national religion (though not, Coffey asserted, a national church) and insisted on congregationalism, while still defending toleration for gathered churches. It became very clear that there is no single early-modern English version of civil religion

The theme of complexity was arrived at from a different direction by Charlotte McCallum and Jacqueline Rose, who focused on the potential sources of the idea of civil religion for early-modern English thinkers. McCallum, in a paper on the early-modern translations of Niccoló Machiavelli's works into English, noted that Machiavelli himself offered not one, but two versions of civil religion: false religion used for political purposes (perhaps a negative reading of Beiner's Rousseauian definition) and the appropriation of religious values as good civic values in the style of Numa (which fits more with Goldie's approach). Not surprisingly, McCallum showed that most seventeenth-century writers favoured the latter and actually used Machiavelli's acknowledgement that religion could perform a valuable political role to 'prove' that atheism was wrong. Rose, in a paper entitled 'Civil Religion and the Anglo-Saxon Church', probed the intriguing question of why the Anglo-Saxon system, which might appear a useful home-grown example of civil religion, was not widely used in that way by early-modern writers. Showing the problems that the presence of the clergy within Anglo-Saxon Parliaments raised for those intent on limiting priestcraft, Rose insisted that we should be careful not to collapse royal supremacy into civil religion. What we have, she concluded, is not a single discourse, but a series of languages that overlap with and cross over each other in complex and complicating ways.

The complexities continued after the revolutionary period and on into the eighteenth century, as John Marshall's paper on the extent to which John Locke can be said to have advanced civil religion and Katie East's on debates surrounding religion during the early English Enlightenment made clear. And they become further elaborated if we extend our horizons beyond England, as some speakers did

Statue of Jean-Jacques Rousseau next to the Pantheon in Paris. Photograph by Rachel Hammersley

Nevertheless, much would surely be learned by tracing other national stories in the same detail as has been done for England. Venice would be an interesting case study, and so too would colonial America, which was touched on in Christie L. Maloyed and Andrew Murphy's paper 'Civil Religion on the Ground: Theory and Practice in Early Pennsylvania'. They showed how some of the ideas that had been developed in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England were not only put into practice, but also transformed in the rather different circumstances of colonial and revolutionary America. A comparison with the French case too might prove particularly revealing. An account that examined Gallicanism, Jansenism, the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, and the Cult of the Supreme Being, setting them against traditional understandings of civil religion and the English case could be fruitful. Some of the important distinctions here were flagged up in Delphine Doucet's paper, which showed that Rousseau was at odds with other figures within the traditional canon - not least Machiavelli and Thomas Hobbes - in his insistence that both natural religion and toleration were crucial to civil religion, and in his refusal to see priests as civil servants. To what extent this distinctive perspective was coloured by Rousseau's Genevan roots, or indeed, by his French connections, is as yet unclear.

Coming away from this conference, as with the previous one, I very much wished that I had the time necessary to follow up all the fascinating intellectual threads that had been revealed.