Last month's blogpost focused on the relevance of the title and frontispiece of Hobbes's Leviathan for Harrington's work. In this month's post I want to develop these observations by examining Harrington's engagement with the language and argument of Hobbes's Introduction to that book, and the contrasting approaches to 'political science' of these two seventeenth-century thinkers.

The opening passage of Leviathan not only provided Harrington with his title, as I showed last month, but is also referenced repeatedly in his works. It is, therefore, worth quoting in full:

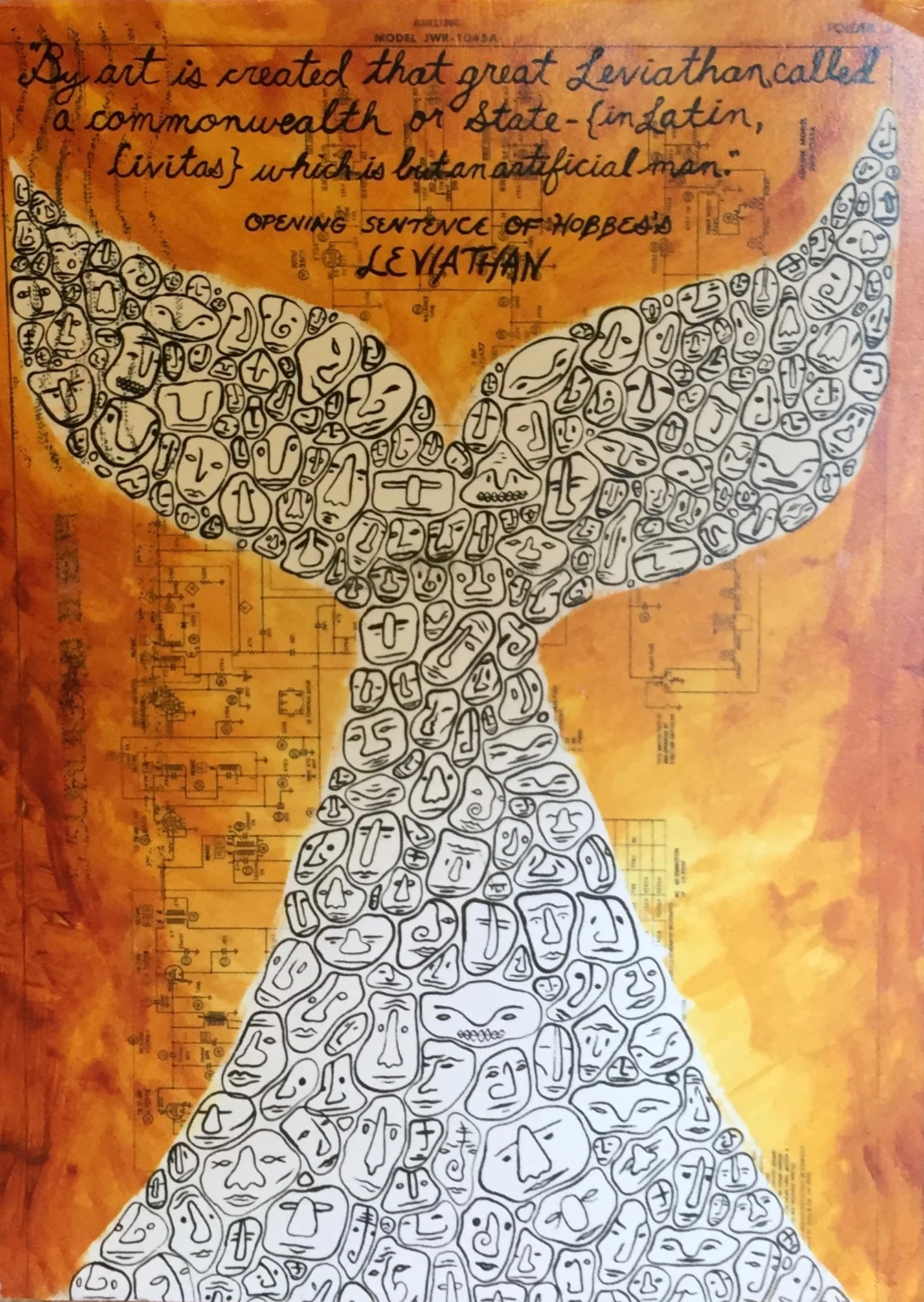

Postcard depicting an artistic reinterpretation of Hobbes’s Leviathan by Matt Kish.

NATURE (the Art whereby God hath made and governes the World) is by the Art of man, as in many other things, so in this also imitated, that it can make an Artificial Animal. For seeing life is but a motion of Limbs, the beginning whereof is in some principall part within; why may we not say, that all Automata (Engines that move themselves by springs and wheeles as doth a watch) have an artificiall life? For what is the Heart, but a Spring, and the Nerves, but so many Strings; and the Joynts, but so many Wheeles, giving motion to the whole Body, such as was intended by the Artificer? Art goes yet further, imitating that Rationall and most excellent worke of Nature, Man. For by Art is created that great LEVIATHAN called a COMMON-WEALTH, or STATE (in latine CIVITAS) which is but an Artificiall Man; though of greater stature and strength than the Naturall, for whose protection and defence it was intended; and in which, the Soveraignty is an Artificiall Soul, as giving life and motion to the whole body (Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, ed. Richard Tuck, Cambridge, 1991, p. 9).

Harrington even gave the title The Art of Lawgiving to one of his books. Taken from: The Oceana and other works of James Harrington, ed. John Toland (London, 1737). Private copy. Image by Rachel Hammersley.

In The Mechanics of Nature Harrington echoed Hobbes in describing 'Nature' explicitly as 'the Art of God' (James Harrington, The Mechanics of Nature in The Oceana and Other Works of James Harrington, ed. John Toland, London, 1737, p. xlii). Elsewhere he too presented constitution-building or 'lawgiving' as an art, suggesting that by practising it humans could imitate God's creativity. And like Hobbes, Harrington also drew on the analogy of the body politic:

AS the Form of a Man is the Image of God, so the Form of a Government is the Image of Man.

...

FORMATION of Government is the creation of a Political Creature after the Image of a Philosophical Creature; or it is an infusion of the Soul or Facultys of a Man into the body of a Multitude (James Harrington, A System of Politics in The Oceana and Other Works, p. 499).

Of course, the body-politic analogy had a long history and was, by the mid-seventeenth-century, a rather outdated metaphor. Yet neither Hobbes nor Harrington was using it in a purely conventional way. Both men sought to revolutionise the idea of the body politic and, with it, politics more generally.

Hobbes saw the body politic as an artificial rather than a natural body - more like a machine than a human being. Against this, Harrington was keen to emphasise that while government is a human creation, legislators are still bound to follow the dictates of nature as laid down by God:

Policy is an Art, Art is the Observation or Imitation of Nature, Nature is the Providence of God in the Government of the world, whence he that proceeds according unto Principles acknowledgeth Government unto God, and he that proceeds in defiance of Principles, attributes Government unto Chance, which denying the true God, or introducing a false One, is the highest point of Atheisme or Superstition (James Harrington, The Prerogative of Popular Government, London, 1658, 'The Epistle Dedicatory').

It is in this context that we can understand Harrington's choice of title as a response to Hobbes. While the Leviathan cannot be constrained by any human form (as the quotation from the book of Job that appears on Hobbes's frontispiece declared), it is nonetheless constrained in only being able to survive in the ocean and not on land.

William Harvey, Exercitatio Anatomica Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus (Florence, 1928). Reproduced from a copy held in the Special Collections department of the Robinson Library, University of Newcastle. Pybus C.v.09. With thanks to Sam Petty.

While rejecting the idea of government as machine, Harrington nevertheless did not revert to the traditional notion of the body politic. Where these supported monarchy (with the king generally associated with either the head or the heart) Harrington offered a more democratic interpretation. He also drew an analogy between this interpretation and the ideas of one of the leading scientists of his day - who was also, significantly, a friend of Hobbes - William Harvey.

Harrington justified his bicameral legislature, and the rotation of office that operated in both houses, by reference to Harvey's theory of the circulation of the blood:

So the parliament is the heart which, consisting of two ventricles, the one greater and replenished with a grosser store, the other less and full of a purer, sucketh in and gusheth forth the life blood of Oceana by a perpetual circulation (James Harrington, Oceana, London, 1656, p. 190).

Through adopting Harvey's notion of the heart as a pump composed of ventricles with distinctive functions, and of the blood as the life-force of the body - here equivalent to the people - Harrington implies that his theory is in tune with current scientific development. Yet the heart, on this account, represents not the king (as Harvey himself had suggested) but the legislature, thereby turning Harvey's (and by association Hobbes's) monarchism against them by showing that the body politic metaphor is capable of a democratic reading.

Harrington's desire to demonstrate his credibility as a scientific thinker has tended to be obscured by the recent emphasis on his status as a classical republican. Yet, like Hobbes, he was keen to put politics on a scientific footing.

Harvey, Exertatio Anatomica, pp. 56-7 from the Robinson Library edition.

Hobbes set out his vision of a science of politics in The Elements of Law and in De Cive. The approach he took was hinted at in the title of the former, which echoed that of the English translation of Euclid's famous work: The Elements of Geometry. For Hobbes, true scientific knowledge was not 'prudence' but 'sapience' and could only be arrived at via deductive reasoning. Hobbes dismissed prudence as mere experience of fact which was used 'to conjecture by the present, of what is past, and to come' (Thomas Hobbes, The Elements of Law Natural and Politic, ed. Ferdinand Tönnies, Cambridge, 1928, p. 139). Harrington, by contrast, adopted this inductive approach as the foundation of his scientific knowledge, expressing the basic principle of his own political reasoning as follows: 'what was always so and no otherwise, and still is so and no otherwise, the same shall be so and no otherwise' and he insisted that we can be as certain of this as we are of other scientific principles. Responding to the criticism Hobbes had made of Aristotle and Cicero - that they had derived their politics not from the principles of nature, but from the practices of their own commonwealths, just as grammarians produce the rules of language from the writings of poets - Harrington suggested that this was equivalent to saying that Harvey had discovered the circulation of the blood not on the basis of the principles of nature, but through studying the anatomy of a particular body (James Harrington, Politicaster, pp. 47-8). Harrington, thereby, likened his political methodology to the scientific methodology of anatomy:

Certain it is that the delivery of a model of government (which either must be of none effect, or embrace all those muscles, nerves, arteries and bones, which are necessary to any function of a well-ordered commonwealth) is no less than political anatomy (James Harrington, The Art of Law-giving, London, 1659, III, p. 4).

In Politicaster he repeated this point in language that deliberately echoed Hobbes: 'Anatomy is an Art; but he that demonstrates by this Art, demonstrates by Nature, and is not to be contradicted by phansie, but by demonstration out of Nature. It is no otherwise in the Politicks' (Harrington, Politicaster, p. 44). What this indicates is that Harrington was intent on basing his analysis not, as Hobbes did, on deductive logic, but, as Harvey did, on the analysis of specific models, both living and dead. In drawing on Harvey, and in coining the phrase 'political anatomy', Harrington further underlined the modern and scientific character of his thinking, pursuing Hobbes's aim to set politics on a scientific footing, while showing that Hobbes at best offered too narrow an account of what this would involve and at worst had misrepresented scientific methodology.

Harrington was playing a cunning game with Hobbes, opposing his politics 'to shew him what he taught me'. However, it was not successful. While Harrington frequently refers to Hobbes in his work, both explicitly and implicitly, the interest was not mutual. Hobbes never responds directly to Harrington's provocations, and does not appear to have engaged with his ideas. It would seem he had little interest in what he had taught Harrington - or in what Harrington might have been able to teach him.