Durham on the morning of Thursday 18th September 2025. Image by Rachel Hammersley.

On Thursday 18th September I enjoyed a last fling of summer freedom before term began in earnest. On a bright and sunny morning I took the train to Durham for a workshop I had planned alongside two colleagues, Jamie Gianoutsos and Amanda Herbert. The seed had been sown at a conference almost exactly two years earlier, when I heard Jamie speak about her research on the medical writings of Marchamont Nedham and their relevance for his political ideas. It struck me that there were interesting similarities between Nedham's thought in this area and the ideas of his fellow republican author James Harrington. Both men drew on Helmontian thought, particularly the notion of vital spirits; and in both cases there appeared to be a direct connection between medical theories and republican politics. My intellectual biography of Harrington includes a chapter on his natural philosophy in which I explored his ideas on this topic, but I had always felt that there was more to be said

The plan to pursue our shared interests in this topic was encouraged by two factors. First that Jamie, who is based in Maryland in the US, was going to be in Dublin for the autumn semester of 2025, and secondly that in the intervening period I kept coming across other scholars whose work seemed to touch on similar ideas - including Gio Maria Tesserola on Harrington and John Streater and Tom Ashby on Algernon Sidney. Slowly, the plans for the workshop began to take shape. IMEMS at Durham very kindly agreed to host us. Keen to keep things as informal as possible - and to involve colleagues based abroad who could not travel to Durham for the occasion - we opted for a hybrid format and for sharing and discussing primary sources rather than presenting full papers. By the beginning of September we had nine speakers and several other interested participants. What follows are my reflections on some of the themes that emerged from our discussions.

The metaphor of the body politic was not distinctive to republican thought, it had also been central to traditional monarchical understandings of kingship. James VI and I drew on the idea in The Trew Law of Free Monarchies:

And the proper office of the king towards his subjects agrees very well with the

office of the head towards the body and all members thereof, for from the head,

being the seat of judgement, proceeds the care and foresight of guiding, and

preventing all evil that may come to the body or any part thereof. The head cares

for the body: so does the king for his people. As the discourse and direction flows

from the head, and the execution according thereunto belongs to the rest of the

members, every one according to their office, so it is betwixt a wise prince and his

people.

(James VI and I, The Trew Law of Free Monarchies (London, 1598).

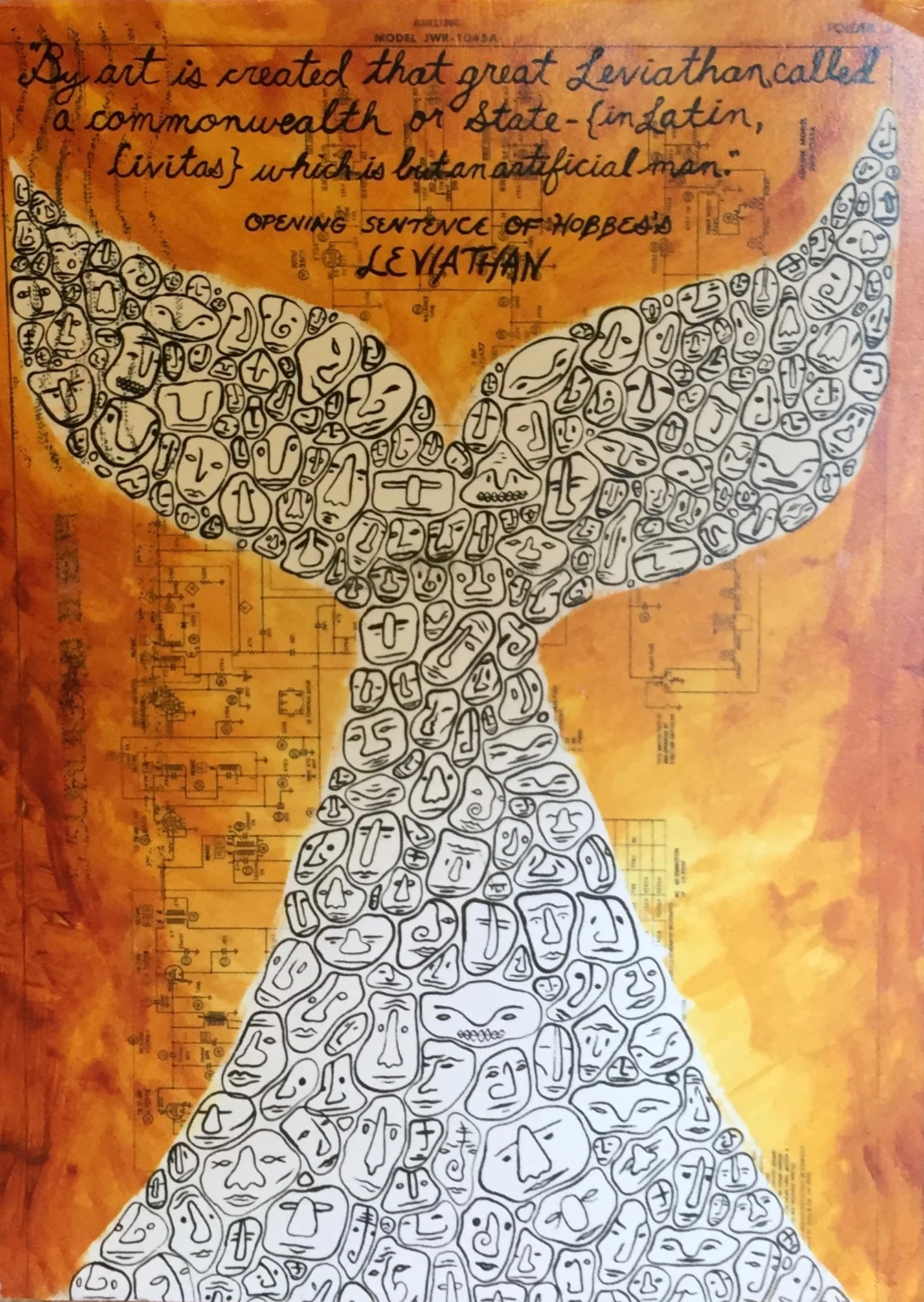

The body politic metaphor was also deployed by Thomas Hobbes who described the state as a union understood as a civil person or an artificial man. This raises the question of why republican thinkers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries drew on this monarchical commonplace of the body politic to articulate their understanding of politics?

One obvious reason for the widespread deployment of this metaphor is its utility. Like human bodies, bodies politic tend to be subject to periods of health and sickness, and just as doctors seek ways of establishing and prolonging health and preventing illness in their human patients, so those interested in politics and government are keen to promote the well-being of the body politic and stave off corruption and decay.

Algernon Sidney, after Justus van Egmont, based on a work of 1663. National Portrait Gallery, NPG 568. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

In this regard, the experience of ancient Rome was an obvious exemplum for early modern thinkers. Several workshop contributors commented on the fact that the decline and fall of Rome often served as a reference point. For example, Jamie noted that the advanced age (and associated corruption) of the Roman state was said to be reflected in the fact that the men were perfumed and had soft hands. In his paper, Tom Ashby pointed to Algernon Sidney's views on this issue. Sidney insisted, that owing to the Fall, corruption and death (of both the human body and the body politic) were unavoidable and the perfection of virtue impossible. He used analogies with athleticism and physical perfectibility to illustrate this. In the Discourses Sidney described the accumulation of wealth in Rome by the state and by private men as 'a most dangerous disease, like those to which human bodies are subject when they are arrived to that which physicians call the athletick habit, proceeding from the highest perfection of health, activity and strength' (Algernon Sidney, Discourses Concerning Government, Chapter 2, 14). Sidney saw value in striving for perfection (even if it was unattainable), but he cautioned that as the state got close to the peak of perfection greater vigilance was needed to maintain health and stave off corruption.

Other papers, too, emphasised this idea of vigilance. In her discussion of colonial America, Becca Palmer noted the intertwining of the moral and the political in the republican ideal of a watchful citizenry. In this colonial context, the vigilance of citizens was deemed crucial to the preservation of both bodily and state health and the avoidance of decay. Jamie demonstrated that vigilance was also an important concept for Marchamont Nedham, who emphasised the threat of disease and corruption coming not just from outside the body but also from within. He spoke of the craftiness of disease and of the need to be on guard to prevent it from taking hold.

While some early modern writers stressed the need for vigilance, others insisted on the need to purge corrupt elements. Borbala Pigler noted that in the sixteenth century colonisation was seen as a means of purging a diseased and stagnant body politic, by offering an outlet for the excessive or corrupt elements of the population. By the eighteenth century, as Amanda explained, the purging of the body through blood letting was likened to elections - for example by Benjamin Rush. On his account, elections were a means of casting out corrupt members and replacing them with fresh alternatives.

‘The Manner and Life of the Ballot’ from John Toland’s edition of The Oceana and Other Works of James Harrington (London 1737). Volume author’s own. Image by Rachel Hammersley.

Frequent elections were also seen as a means of staving off corruption in the writings of seventeenth-century republicans. Here the emphasis was on avoiding stagnation and decay through constant movement - drawing on the idea of flowing water in a river or blood in the body. Both Harrington and Nedham insisted that there should be constant movement of the people within the body politic through rotation of office, since allowing any individual to remain in power for too long ran the risk of corruption. Becca noted that in eighteenth-century America paper money was viewed in similar terms as a way of ensuring constant movement within the state and thereby staving off degeneration.

A second theme that emerged from our discussions centred on the idea that while bodies epitomise our shared humanity (and therefore our shared membership of the republic) there was also a sense in the past of the need to treat different bodies differently. This problem was introduced in theoretical terms in Borbala's contribution on 'The justice of the body politic' in which she showed how in sixteenth-century England Aristotle's notion of distributive justice was applied to both the state and the human body. According to this understanding, each separate part (each organ or each member of the body politic) had to function well in order for the whole to remain healthy. This was, of course, different from saying that all had to be treated the same or to be given the same role, and in this way it allowed for the inclusion of different groups. For example in the publication Here Begynneth the Kalender of Shepardes (London, 1518) which, as Borbala showed, was suffused with the Aristotelian conception of justice, women were included as a category in their own right (not simply as wives or daughters) and their main duty was obedience. Though it is interesting to note that the Kalender also refers to female shepherds who serve the same function - and are therefore to be treated the same - as their male counterparts.

Leila Marhamati gave a striking example of an unconventional female bodily metaphor for the body politic taken from Machiavelli's Discourses that was originally highlighted by John Freccero. Alongside the conventional allegory of the passive female body politic that was subject to violation by invaders, Machiavelli offered the example of Caterina Sforza. When her fortress was under attack, Sforza is said to have responded to the threat that her sons would be killed, by lifting up her skirts and reminding her opponents that if they carried out this threat, she had the power to make more children. As Leila highlighted, this used the generative power of women as the basis for their claim to a more active role within the body politic. Of course, the notion of republican motherhood was an idea that was picked up later on, not least in a colonial context. Yet Leila cited letters sent to John Adams when he was President that demonstrate the complexity of this notion. Some women reported urging their sons to fight for the defence of their country, clearly accepting the sacrifice they may have to endure as a result. Others appealed to Adams as a parent himself, insisting that his focus should be on striving for a more secure and prosperous future for their children and grandchildren.

In practical terms there was a recognition that male and female bodies were different and needed to be treated differently. Amanda explained that eighteenth-century spas were open to men and women but that women tended to go with different ailments from men; and there was also a sense that women might need a gentler regime to avoid being overwhelmed. By contrast, black male bodies, which were also treated at colonial spas, would often be subjected to particularly harsh regimes on the grounds that it would make them more productive labourers.

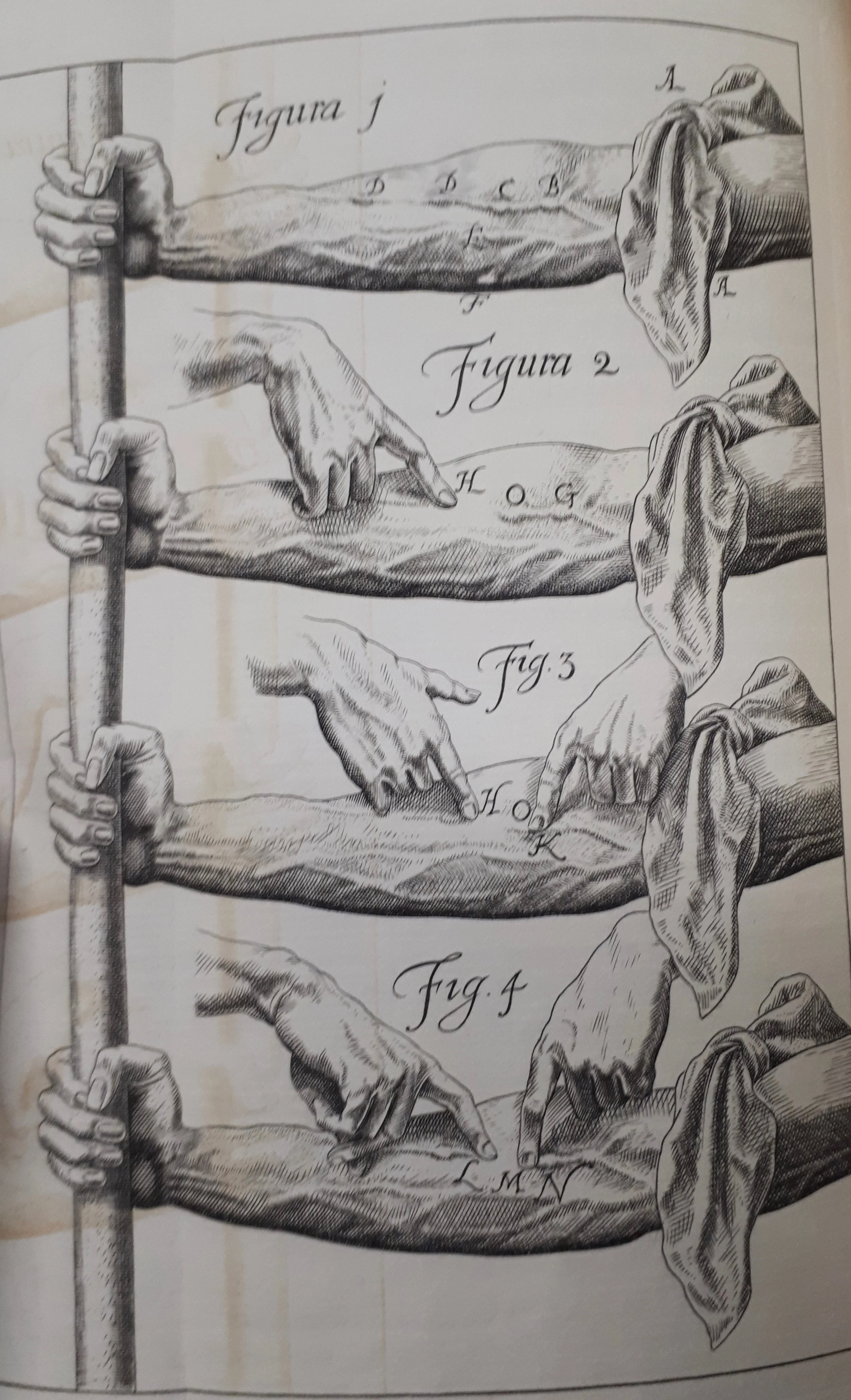

Image from William Harvey’s Exercitatio Anatomica de moto cords et sanguines in animali (1628). Reproduced with permission from the Philip Robinson Library. Special Collections. Pybus Collection Pyb. C. v.9.

Finally, our discussions prompted some methodological reflections on approaching a topic like this from a modern perspective. The disciplinary boundaries that we take for granted did not exist before the nineteenth century, so a thinker like Nedham would probably not have seen his medical work as divorced from his political thinking as we do today. Moreover, in the case of those (like Nedham, Harrington, and Streater) who were influenced by Helmontian thought, there is the difficulty of trying to make sense of their understanding of ideas that we now know to be false. As Gio Maria noted when thinking about Harrington's debt to the scientific theories of Francis Bacon and William Harvey, we need to remember that these figures too were influenced by alchemical, magical and theological approaches to the study of nature. Gio Maria reminded us that the seventeenth century was a transitional period, one in which thinkers were deliberately seeking to adapt older ideas to the new republican cause.

Samantha Wesner's talk on the application of theories about electricity to politics during the French Revolution suggested that something very similar was going on at that transitional moment. She showed that electricity became an important metaphor for republican politics at the time. This was in part because it helped to make sense of the difficult - but crucial - republican concept of the general will. French republicans in the early 1790s were grappling with just how a republican nation could be made to cohere and move as one. At that time electricity was a new scientific discovery and, like the general will, it was invisible and therefore difficult to comprehend. Yet, in the demonstrations that were common at the time, groups of people could be made to feel the power of electricity as a small shock was passed around the group. Electricity then was a helpful metaphor as republicans reached towards new political ideas that they did not fully comprehend.

So, while it may have started out as a metaphor for monarchical politics, the body politic - and the application of scientific theories to politics that was associated with it - proved useful to the articulation, and even understanding, of new republican ways of thinking about politics.