Frontispiece to James Harrington, The Commonwealth of Oceana in The Oceana and Other Works of James Harrington, ed. John Toland (London, 1737). Private copy.

George Monbiot's book Out of the Wreckage: A New Politics for an Age of Crisis calls for the creation of a "politics of belonging". He is not the only person to suggest, in recent months, that a new way of thinking about politics is required. These calls have prompted me to think again about the utopian character of James Harrington's The Commonwealth of Oceana.

Historians have long debated whether Oceana should be labelled as a utopia at all, partly because it was very clearly intended as a practical model for a specific place and time. Yet Colin Davis, author of Utopia and the Ideal Society, sees this as precisely one of the key features of a utopia. Davis argues that what distinguishes utopias from other conceptions of the ideal society is their acceptance that limited resources are exposed to unlimited desires: 'The utopian's method is not to wish away the disharmony implicit within the collective problem, as the other ideal-society types do, but to organise society and its institutions in such a way as to contain the problem's effects.' (Colin Davis, Utopia and the Ideal Society: A Study of English Utopian Writing 1516-1700, Cambridge, 1981, pp. 37-8). This kind of model, one that takes human society as it is and offers practical solutions to human problems - and yet pushes beyond the framework of the current system - is precisely what we need just now. So what would an Oceana for the twenty-first century look like?

It will come as no surprise to readers of this blog that, in the first place, my twenty-first century Oceana would seek to challenge the idea that politics is the preserve of a distinct political class. Harrington, following Aristotle, believed every citizen should rule and be ruled in turn. He also insisted that human nature dictated that individuals who held power for long periods of time (however good and virtuous they were in the first place) would inevitably become corrupt. Harrington's solution was the rotation of office, with representatives being in post for three years before standing down and being ineligible for re-election for a similar term. Something like this system could be introduced in the UK Parliament. Of course there are problems that would need to be addressed. Being effectively made redundant after three years may deter certain individuals (perhaps particularly the poorest) from standing at all, so jobs would need to be held open and provision made to support those retiring from office. But the potential advantages of politics being an activity in which most citizens engage at some point, rather than the preserve of a political élite, are significant.

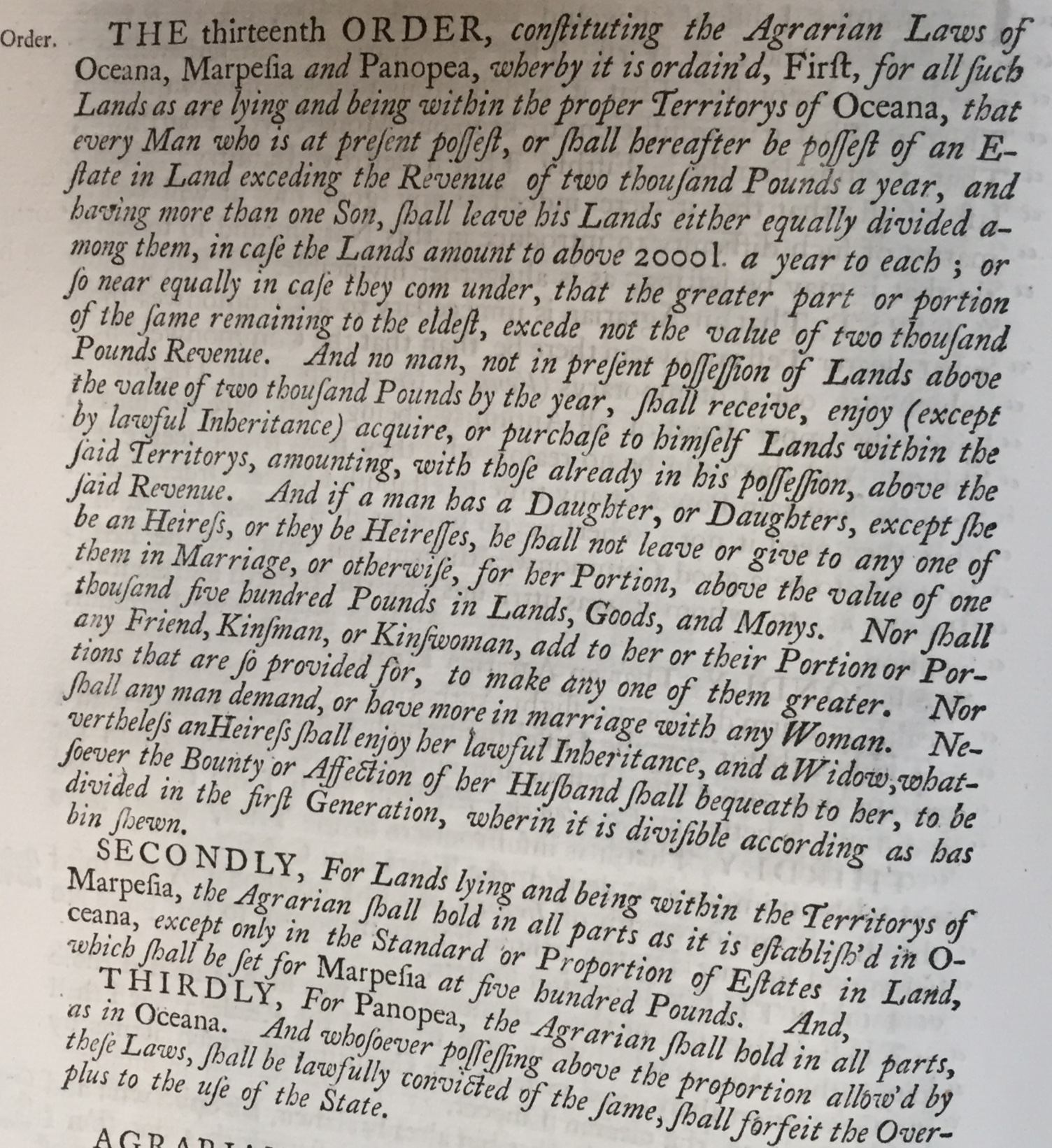

Thirteenth order of Harrington's Oceana on the agrarian law.

Another central tenet of Harrington's political programme was the preservation of an equitable division of land within the nation. This was necessary to maintain a balance of property, and hence of power, suitable for commonwealth government. Harrington sought to achieve this through his agrarian law, which required those owning large tracts of land to divide their estate more equally among their children. While land is still a crucial source of the wealth of the super-rich, it has largely been replaced by money as the basis of power. My concern here is not with the redistribution of property in either its landed or monetary form, but rather with the means by which the majority of us earn our money. Work is currently divided in ways that are uneven, creating unhappiness both among those who have too much and those who have too little. Earlier this year the New Zealand trustee company Perpetual Guardian initiated a six-week trial in which its employees were to work four days a week while being paid for five, and in this country the Autonomy Institute has called for the implementation of a four-day week. I am one of a growing number of parents who have made the switch to working four days a week. While there is a danger (for those of us doing four days' work for four days' pay) of succumbing to the tendency to do five days' work in four, my experience is that a four-day week makes for a better work-life balance, for those able to take it. There are also potential benefits for others since, in my own and many other professions, a large number of highly talented young people are struggling to get their feet on the career ladder. If more people worked fewer days a week then more positions would open up for junior staff. Of course, employers may well complain that it would create a less efficient system. But we could off-set the inefficiencies of having to employ more staff against the efficiencies gained from workers being less tired, more motivated, and less susceptible to stress and its associated health problems. Nor should this change in work patterns be available only to professionals. A wholesale reconsideration of what constitutes a working week ought to address changes and benefits that can be brought to all workers.

Finally, Harrington's commitment to healing and settling a divided nation could be developed for the twenty-first century. As I demonstrated in a previous blogpost, he insisted that peace could only be established in post-civil war England if those on both sides of the royalist-parliamentarian divide were allowed to engage equally as citizens. He was also a strong advocate of religious toleration, insisting that no-one's right to citizenship or to hold office should be rescinded on the basis of religious belief. The Brexit Referendum, along with the debates at home and negotiations in Europe that have followed, have created deep divisions in our society. As a result, we too are in need of healing and settling. I suggest, though, that the solution for us lies less in extending citizenship to those who are currently excluded than in making political citizenship more substantial.

John Milton by William Faithorne, line engraving, 1670. National Portrait Gallery NPG D22856. Reproduced under a Creative Commons License.

One way of doing this would be to encourage open debate about key issues. This might be seen as going against Harrington's ideas, in that his popular assembly was not allowed to discuss legislative proposals - he worried that popular political debate would lead to anarchy. Yet he saw debate by the Senate as crucial to the political process, and he did not want to prevent popular debate from taking place outside the popular assembly. Moreover, in several of his writings he expressed the idea that greater knowledge would arise from the debating of issues, even suggesting that his model constitution would be improved by others examining and criticising it. There is an echo here of Milton's notion from Areopagitica that good ideas will inevitably win out if free debate is allowed to flourish. If we could create opportunities at all levels of society for free, open and constructive political debate involving those of different political views, perhaps we could construct a society that is more open, tolerant, and better informed.

Sir Thomas More, after Hans Holbein the Younger, early C17 based on a work of 1527. National Portrait Gallery, NPG 4358. Reproduced under a Creative Commons License.

Of course, what I have offered here is not a utopia but just three proposals inspired by Oceana. A further distinguishing feature of utopias, noted by Davis, is that they are conceived as total schemes. In the early modern era this was often achieved by setting the utopia on a distant island, as Thomas More did in the work that gave its name to the genre. This reflected a fascination with the, as yet not fully charted nature of the globe at that time. While, like More, Harrington was writing a utopia for England, he indicated the intended location more overtly, the fictional guise he employed simply signalled a concern with England as it ought to be rather than as it actually was. Today, the obvious place to situate a utopia would be in the virtual realm. Moreover, with the right software one might even be able to play out the consequences of such a system, as is done in disaster scenario planning (and as Harrington attempted to do in a more basic form in the corollary to Oceana). Perhaps my next step, after my Harrington book has been delivered to the publisher, should be to construct a Harringtonian 'digitopia'.