The author’s copy of Eric Nelson’s book. Image Rachel Hammersley.

I am currently co-teaching a module on 'The Scientific Revolution'. Consequently, Isaac Newton's famous comment to Robert Boyle about 'standing on the shoulders of giants' was already in my mind on 15th February when I attended a symposium at St Andrews. This was organised by Ariane Fichtl to discuss Eric Nelson's important book The Greek Tradition in Republican Thought, which was first published 20 years ago. In his remarks Eric commented that he had wondered beforehand what he would like to hear from those who were gathered to discuss his book. He quickly realised that, while being told 'you were right' would be flattering, it would also be rather disappointing. What he was hoping for, then, was for his book to have provoked thought and discussion and that the conversations inspired by it were still ongoing.

Of course, as Eric would be the first to note, he was himself standing on the shoulders of giants. This point was made explicitly in Quentin Skinner's opening paper in which he presented a useful typology of scholars. There are, he argued, supporters (who champion the work of those who have gone before) and challengers. The challengers can then be divided into contradictors (who insist that those who have come before have got it wrong) and supplementers (who praise past work, while suggesting that something important has been missed). The Greek Tradition in Republican Thought, Quentin suggested, is a good example of this last approach.

Quentin Skinner speaking at the symposium. Image courtesy of Lightbox St Andrews.

Prior to the publication of Eric's book, work on republicanism - including that of Quentin Skinner himself - had tended to emphasise the Roman origins of early modern republican thought. On this account, the ultimate purpose of life was to attain honour or glory. Crucial to this pursuit was a view of liberty as independence, which was grounded in the fundamental Roman distinction between a free person and a slave. What characterised a free person was that they were not dependent on the will of anyone else. This entailed living under the rule of law (not the arbitrary will of a sovereign) and having influence over the making of those laws (whether directly or via representatives). Moreover, those laws ought to protect the life, liberty, and property of the citizens, so that the understanding of justice at the heart of this Roman conception of republican rule involved 'giving each their due'.

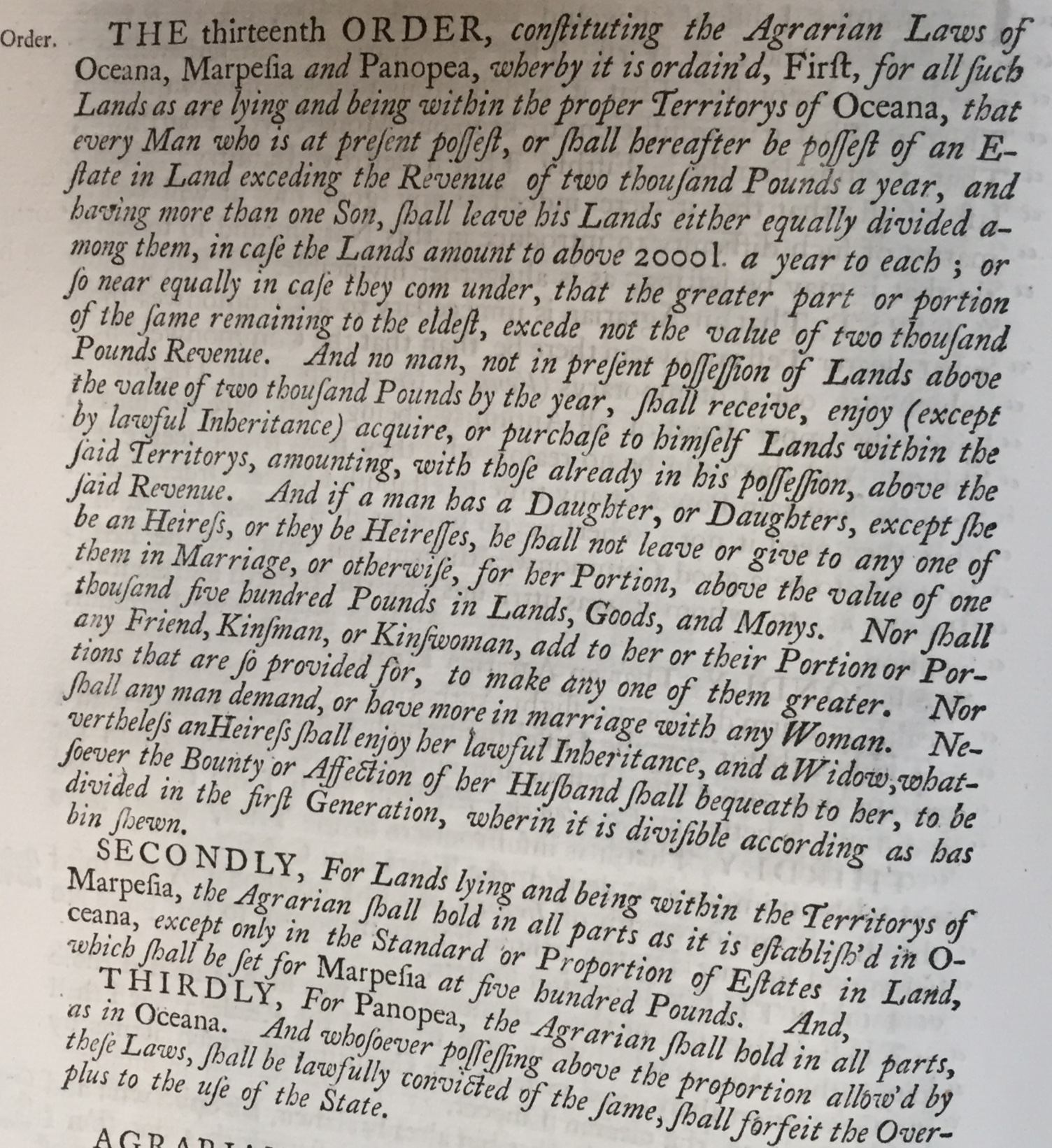

What Eric had noticed was that while this Roman version of republicanism was certainly influential in early modern Europe, it was not the only one. Alongside it there developed an alternative understanding of republican rule that was more indebted to Greek sources. Here the aim was not for citizens to attain honour and glory, but rather to achieve happiness. Consequently, the emphasis was more on the contemplative than the active life. Liberty on this account involved not being enslaved to passion, but being ruled by reason and therefore by individuals who were themselves rational and virtuous. Yet authors in this tradition noted that a threat was posed to this ideal when individuals were able to accumulate wealth, creating a significant gap between rich and poor. Under these circumstances wealth would tend to be valued above virtue, causing corruption. Consequently these authors insisted not on the protection of private property, but rather accepted some measure of redistribution in order to maintain the balance required to ensure the rule of reason and virtue. On the Greek account this balance, or right ordering of the system, was what constituted justice.

Francesco Patrizi. Image taken from Wikimedia Commons.

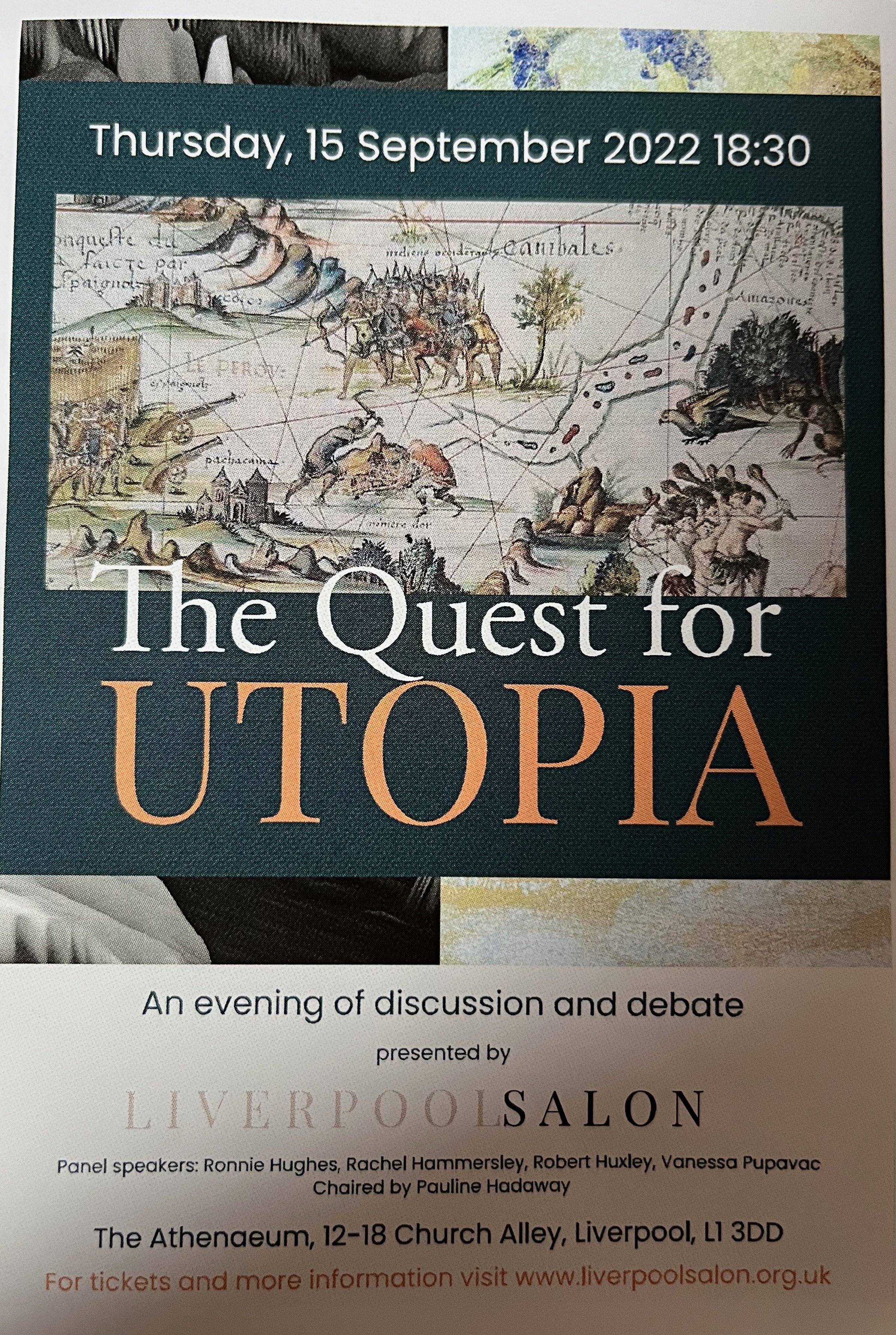

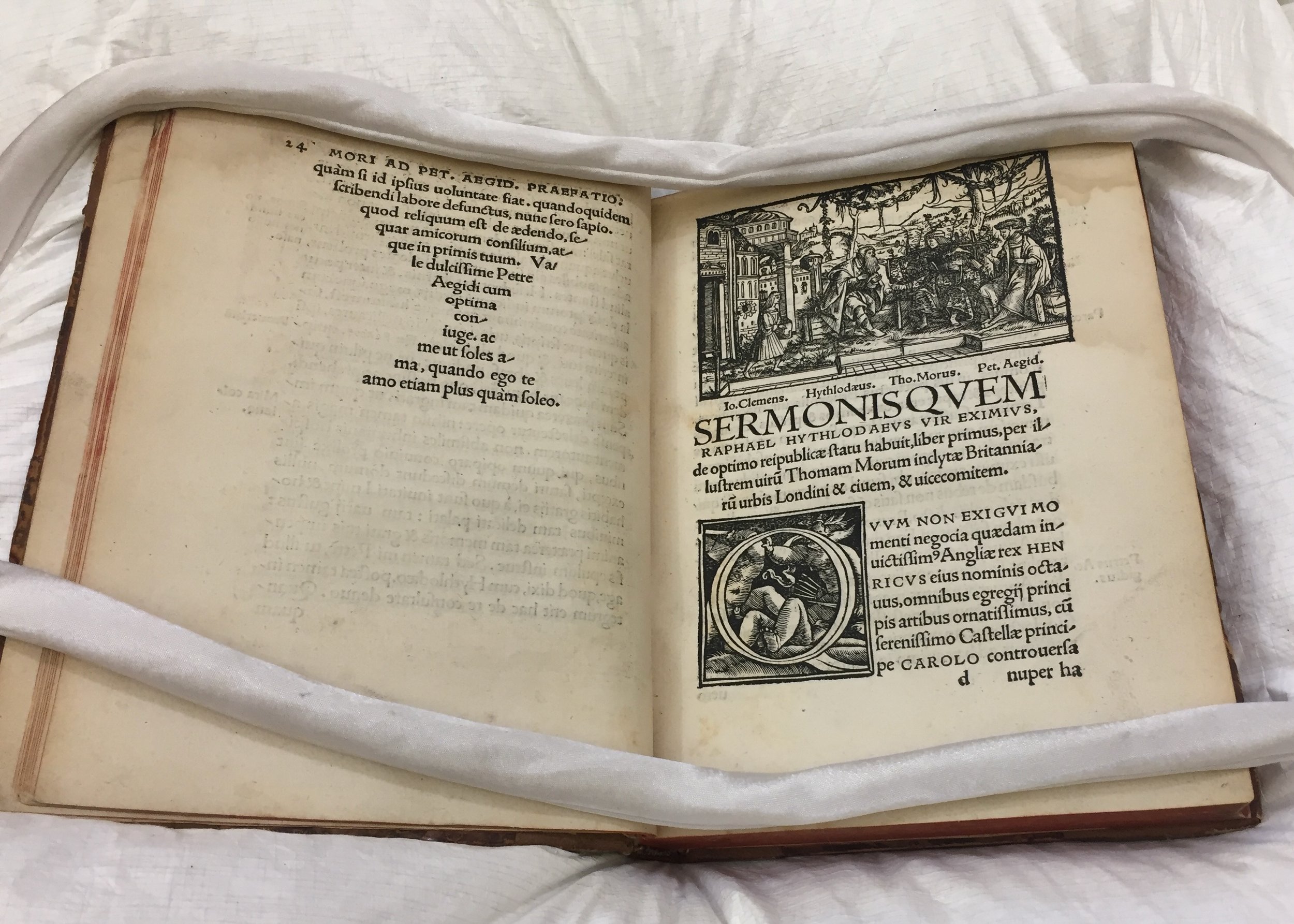

In his book, Eric identified Thomas More, James Harrington, the baron de Montesquieu and others as exemplifying - and developing - this Greek tradition. As Eric himself noted, one way in which the conversation he initiated has been continued is through additions to the tradition. Several papers adopted this approach, proposing figures who did not appear in The Greek Tradition for inclusion. In other words, there was further supplementation.

James Hankins put the case for Francesco Patrizi of Siena. Patrizi drew on recently translated Greek material and adopted a Greek view of private property in line with the model set out in The Greek Tradition. According to Hankins, Patrizi drew a clear distinction between the social hierarchy, where wealth and ancestry were key, and the political order - which should be organised according to virtue and merit.

The grounds for including Patrizi within the Greek tradition seem relatively straightforward. Filippo Marchetti and I made the case for figures whose inclusion is less so, but who nonetheless pose interesting questions for the tradition. Filippo's paper focused on Alberto Radicati of Passeran. He explored the intertwining of republicanism and deism in Radicati's thought, arguing that he had an ethical preference for democracy. In my paper I considered the late eighteenth-century radical Thomas Spence. Spence was directly inspired by Thomas More and James Harrington, and like them he proposed restrictions on landed property to secure a fairer government and society.

A sketch of Thomas Spence's profile from the Hedley Papers at the Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society. Reproduced with permission.

Adding new individuals to traditions often highlights new dimensions. The discussion generated by these and other papers emphasised the importance of education, religion, and democracy

In his discussion of Patrizi, James Hankins noted Patrizi's belief that virtue and merit could be stimulated by education in the classics. A similar claim was made by Isabelle Avci in her paper on Thomas More's biography of Giovanni Pico della Mirandola. Noting that Pico was a controversial figure, and therefore a curious choice for More, she argued that he helped More to address the question of how an individual could maintain virtue while pursuing a political career. For More, as for Pico, education - and, in particular, reading - facilitated the cultivation of virtue through access to the divine. This offered More a means of combining the active and the contemplative life - treating them as complementary - rather than facing a strict choice between the two. Eric had already noted the importance of education in his book and it was crucial to Spence too. In contrast to Patrizi, however, who insisted that all citizens should be taught Latin to break the monopoly of the rich on a classical education and therefore on virtue, Spence and his associates sought instead to render a classical education unnecessary by ensuring that individuals could learn to read, speak, and write just as effectively without this form of learning.

This rejection of the classics could be a reason to exclude Spence from the Greek tradition, along with his democratic bent. As Eric explained, while the Greek tradition does involve the deployment of radical means - in the form of state redistribution of property - it does so in the pursuit of hierarchical ends - namely the rule of those with reason and virtue. Consequently, democracy, despite its Greek roots, was not central to Eric's book - only featuring towards the end in the discussion of a late adaptation of the Greek tradition in Alexis de Tocqueville's reflections on America.

Eric Nelson speaking at the symposium. Image courtesy of Lightbox St Andrews.

Yet several contributors to the symposium explored the theme of democracy, suggesting that it perhaps has more to contribute to the Greek tradition than might initially be thought. In part this is because two types of democracy emerge from the Greek sources. Extreme democracy, which was the focus of Eero Samuel Arum's paper, builds on Aristotle's account of democracy in Book 4 of the Politics, and describes a society in which the multitude has control over the laws. By contrast, restricted democracy draws on Aristotle's notion of politeia. Here sovereignty lies with the people, but virtuous magistrates are chosen by them to rule. The paper demonstrated that Jean Bodin's theory of sovereignty is indebted to this idea. It was also, as Markku Peltonen showed, much discussed by political scientists working in the Holy Roman Empire in the early modern period. Most accepted it as a viable form of government (in contrast to extreme democracy, which they firmly rejected) and some even saw it as the best form. What this tells us, as Markku highlighted, is that representative democracy did not - as was conventionally claimed - emerge fully formed in the age of the democratic revolution, but had its foundations in this tradition. Interestingly, this is also a topic that Eric himself explored in more detail in his Seeley Lectures delivered at the University of Cambridge in 2024.

Mary Wollstonecraft by John Opie, c. 1797. National Portrait Gallery, NPG 1237. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

Building on this democratic theme, several papers considered how Greek ideas could be deployed to justify a widening of the political nation. Hannah Dawson argued that while the Greek tradition looks on the surface to be hostile to women, some early modern feminists quickly found a loophole that they could exploit to argue their case for inclusion. While the notion that the intellectually and morally superior should rule was widely used to exclude women from politics, figures like Mary Astell and Mary Wollstonecraft questioned whether those men who currently hold power are entirely rational and, therefore, fit to rule. Conversely, on this account, rational women should be equally capable of political participation. Hannah also noted that the Greek idea of the contemplative life also offered something to women who could see their minds as free even when constrained under a patriarchal system.

Eran Shalev also touched on the opening up of politics and education to women in his paper on the democratisation of the American Republic in the nineteenth century. His main point, though, and one which was also emphasised in Becca Palmer's paper on debates in colonial American newspapers in the period 1765-1775, was that Greek ideas - and especially the example of Athens - offered a model for democratisation and empowerment.

Ariane Fichtl speaking at the symposium. Image courtesy of Lightbox St Andrews.

Finally three papers looked more explicitly at how the Greek tradition provided practical tools for use in different times and places. Mishael Knight argued that the enclosure commissioner Sir John Hales used Appian's account of ancient agrarian laws to inspire and justify sixteenth-century English agrarian policy. Hales explicitly rejected the Roman notion that justice required giving each their own, insisting instead that redistribution was justified in order to prevent a great distinction between rich and poor. In her closing keynote, Ariane Fichtl showed how the Greek tradition also offered a tool for abolitionists in their development of strong philosophical arguments against slavery. Aristotle's ambiguity on slavery made it possible for abolitionists to use his notion of legal slavery in the Nicomachean Ethics to condemn slavery as tyranny while firmly rejecting his argument in the Politics about the existence of natural slaves. Moreover, unlike its Roman equivalent, the Greek tradition did not insist on an absolute division between dependence and independence, opening the way for the powerful idea of interdependence. Finally Marijn Nolmans's paper suggested that the Greek tradition might offer an alternative to Rawlsian liberalism today. He argued that a combination of the neo-Roman idea of political liberty, Aristotle's notion of human flourishing, perfectionism, and justice understood as the fair distribution of resources, could produce an ideal political society that would not only be free and just, but could also facilitate the flourishing of citizens and encourage excellence in a wide variety of domains.

As can be seen from this, Eric can be assured that conversations sparked by The Greek Tradition have not been exhausted yet

Some of the speakers from the symposium. Image courtesy of Lightbox St Andrews.