We currently find ourselves on a cusp with regard to the materiality of texts. Print copies are still common, but digital editions and open access publishing are on the rise. Yet, for now, the conventions of print tend to provide the framework for digital editions with an emphasis on recreating the look and experience of reading a printed book (for example with 'Turning the Pages' technology) rather than exploring the new possibilities that digital editions might offer.

Despite his experimental use of genre and the blending of fact and fiction, the physical format of Yanis Varoufakis's book Another Now, which I have discussed in previous blogposts in this series, is relatively conventional. It is available in hardback, paperback, as an audio download, and in e-book form with the last of these merely comprising a digital version of the print copy. However, Varoufakis does acknowledge potential innovations in future in his description of what happens when the narrator Yango Varo first opens Iris's diary:

Two red arrows filled my vision as my hybrid-reality contact lenses detected audio-visual content in the diary and kicked in. Instinctively I gestured to switch off my haptic interface and slammed the book shut. Costa had explicitly instructed me to set up the dampening field device before opening the diary. Chastened by my failure to do so, I went to fetch it. Only once the device was on the desk, humming away reassuringly, was I able to delve into Iris's memories in that rarest of conditions - privacy. (Yanis Varoufakis, Another Now: Dispatches from an Alternative Present. London: Bodley Head, 2019, p. 5).

Title page of Toland and Darby’s edition of The Oceana of James Harrington. Reproduced from the copy at the Robinson Library Newcastle University, BRAD 321 07-TP. I am grateful to the Library staff for allowing me to reproduce the work here.

I have already touched on the materiality of early modern texts in previous blogposts (January 2021, September 2020), but there is more to explore. One area of interest is the way in which the material or physical form of a text was deliberately designed to engage a specific audience. During the eighteenth century the English republican works first published during the mid-seventeenth century were directed, in successive waves, at different audiences and the physical format of those editions varied accordingly.

Many of the original English republican texts published during the mid to late seventeenth century had been relatively small, cheap editions. When John Toland and John Darby decided to reprint these works at the turn of the eighteenth century, they deliberately reproduced them as lavish folio editions. We know from personal correspondence that they took care to use high quality paper and the title pages often include words in red type, which was more expensive. The size and quality of these volumes makes clear that they were aimed at a high-status audience - particularly members of the political elite. They were destined for their own private libraries or those used by them. While in one sense this was exclusionary - putting these works (and the ideas contained within them) beyond the means of ordinary citizens - there was a positive reason for doing so. Toland and Darby were keen to make clear that, although these texts had been published in the midst of the chaos of the civil war and interregnum, they remained of interest - and of relevance to those in government - even after the restoration of 1660. These works were not mere ephemera, but were of lasting significance and continued relevance in the eighteenth century even though England was no longer ruled as a republic.

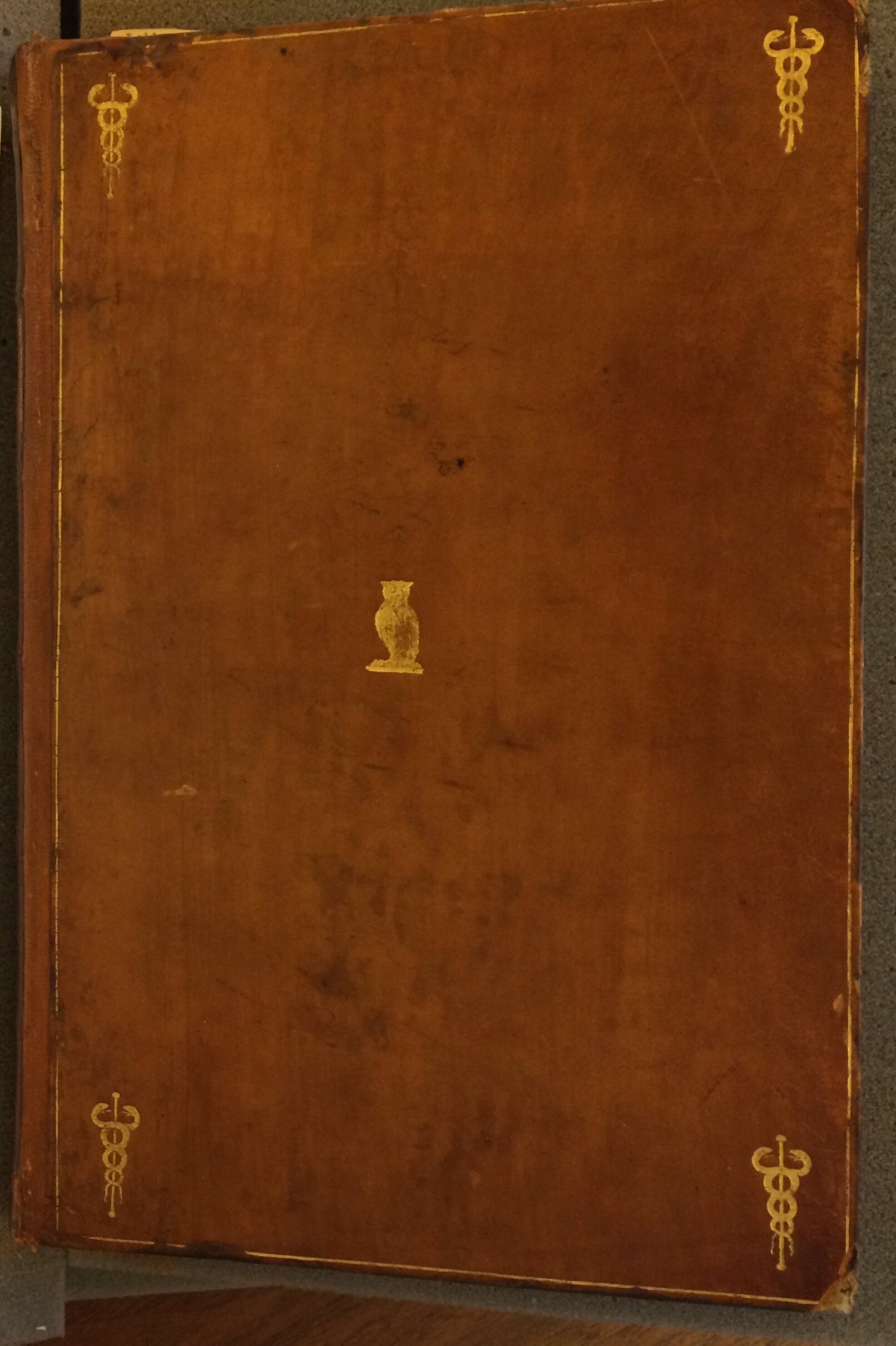

Binding of Thomas Hollis’s edition of Harrington’s works. From Houghton Library, Harvard University. HOU GEN *EC65.H2381 656c (B) Lobby IV.2.18. I am grateful to the Houghton Library for giving me permission to reproduce this and to Dr Mark Somos for his assistance.

Thomas Hollis was aware of Toland's publishing campaign and built his own on its foundations. He republished many of the same texts, and again did so in the form of lavish folio volumes with expensive bindings. Hollis commissioned the Italian engraver Giovanni Cipriani to produce portraits of the authors to preface the volumes and to design little emblems that could be embossed onto the front as a key to the nature of the work inside. However, Hollis's dissemination strategy was aimed less at the private libraries of the elite and instead at institutional libraries - public libraries such as those established in cities like Leiden in the United Provinces and Bern in Switzerland, but also the libraries of educational establishments such as Christ's College Cambridge and, most famously, Harvard in the United States. This suggests that Hollis's target audience was less the current political elite than that of the future. His aim was to educate the next generation - especially in America where, from the 1760s, a crisis was brewing.

The American Revolution, when it came, had a significant impact on both sides of the Atlantic. The slogan 'no taxation without representation' flagged up political inequalities in Britain and provided fuel for the incipient reform movement. To further the cause of reform, the Society for Constitutional Information (SCI) was established in 1774. Its main mode of operation was to print cheap copies of political texts which were disseminated freely. In particular, members of the SCI believed it necessary to educate the people on the nature of the British constitution. As the Address to the Public, published in 1780, explained

John Jebb, one of the founder members of the Society for Constitutional Information. Portrait by Charles Knight, 1782. National Portrait Gallery NPG D10782. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

As every Englishman has an equal inheritance in this Liberty; and in those Laws and that Constitution which have been provided for its defence; it is therefore necessary that every Englishman should know what the Constitution IS; when it is SAFE; and when ENDANGERED (An Address to the public, from the Society for Constitutional Information. London, 1780, p. 1).

The Society focused on printing works that contributed towards this mission, stating that:

To diffuse this knowledge universally throughout the realm, to circulate it through every village and hamlet, and even to introduce it into the humble dwelling of the cottager, is the wish and hope of this Society.

Consequently, the SCI disseminated works such as Obidiah Hulme's Historical Essay on the English Constitution, but also extracts from older works that spoke to these issues. Yet, as the statement of intent makes clear, the Society aimed to disseminate political works not simply among an elite, as their predecessors had done, but throughout the population. This, it was believed, was the best means of awakening people to their rights and thereby furthering the case for the reform of Parliament.

The SCI continued to function into the 1790s and was, therefore, well placed to capitalise on further calls for reform sparked by the outbreak of the Revolution in France in 1789. In this febrile atmosphere, others took up the cause of educating the ordinary people about their rights by making available to them important political texts from past and present.

Spence token advertising Pig’s Meat. Reproduced from Wikimedia Commons.

In 1793 the Newcastle-born radical Thomas Spence published the first issue of a weekly publication entitled Pig's Meat; or, Lessons for the Swinish Multitude, which printed extracts from political texts including from works that had been republished by Toland and Darby or Hollis. The title was a reference to Edmund Burke's derisory comment in Reflections on the Revolution in France which referred to the ordinary people as swine. Spence's publication cost just 1 penny, making it affordable even for those who were relatively poor, and as he explained on the title page, his aim was 'To promote among the Labouring Part of Mankind proper Ideas of their Situation, of their Importance, and of their Rights. AND TO CONVINCE THEM That their Forlorn Condition has not been entirely overlooked and forgotten, nor their just Cause unpleased, neither by their Maker nor by the best and most enlightened of Men in all Ages.' Alongside his Pig's Meat publications, Spence engaged in other means of spreading political ideas including writing works of his own and producing and disseminating tokens.

What is the relevance of all this? First, it reminds us that it is not just the content of political works that matters, but also the form in which they are printed, and the way they are disseminated and read. Literary critics like George Bornstein, inspired by Jean Genet and Jerome McGann, have been making this point for some time. But it has yet to fully penetrate the historical investigation of political texts. Secondly, the attempt by authors, editors and reformers to reach ever wider sections of the population during the course of the eighteenth century is striking. It reveals the importance of politics to eighteenth-century British society and the firm belief (at least on the part of some) that political education could and would bring political reform. Is there, I wonder, the same appetite for political knowledge today? What kind of publications would best attract twenty-first century audiences? And what kinds of reform might they propose?