The events of the last two weeks have brought to the fore the relationship between the individual and society. The spread of Covid-19, as well as our ability to access food and other basic necessities, depend on whether people behave in their own or the public interest. Moreover, many commentators have noted that this crisis has brought out both the best and worst in people. Though this blogpost was written before the Coronavirus situation in the UK escalated and we were confined to our homes, exploring the role that virtue can and should play in society now seems particularly pertinent.

Those who have written about the history of republicanism tend to agree that two key concepts lie intertwined at its heart: liberty and virtue. Recent scholarship has placed greater emphasis on the former. Particularly influential has been Quentin Skinner's argument that there is a distinctive understanding of liberty popular with past republican thinkers, which insists that freedom requires not just the absence of physical restraint (as the liberal understanding would suggest) but also not being dependent on another person's will. This understanding of liberty as non-dependence is central to Philip Pettit's influential attempt to establish neo-republicanism as an alternative to modern liberalism today. It is no doubt easier for current advocates of republican government to emphasise liberty, which remains a fundamental and respected value in the twenty-first century, than to try to argue in favour of virtue, a value that, aside from aficionados of virtue ethics, brings with it connotations of ancient self-sacrifice and Christian moralising.

Another myth about republican government that potentially amounts to an objection to its revival in the present, then, is that it requires the exercise of an unreasonable degree of virtue on the part of citizens. As with the other myths that have been explored in this blog, there is some justification for this.

Jacques-Louis David, ‘Brutus and the Lictors’ reproduced thanks to the Getty’s Open Content program.

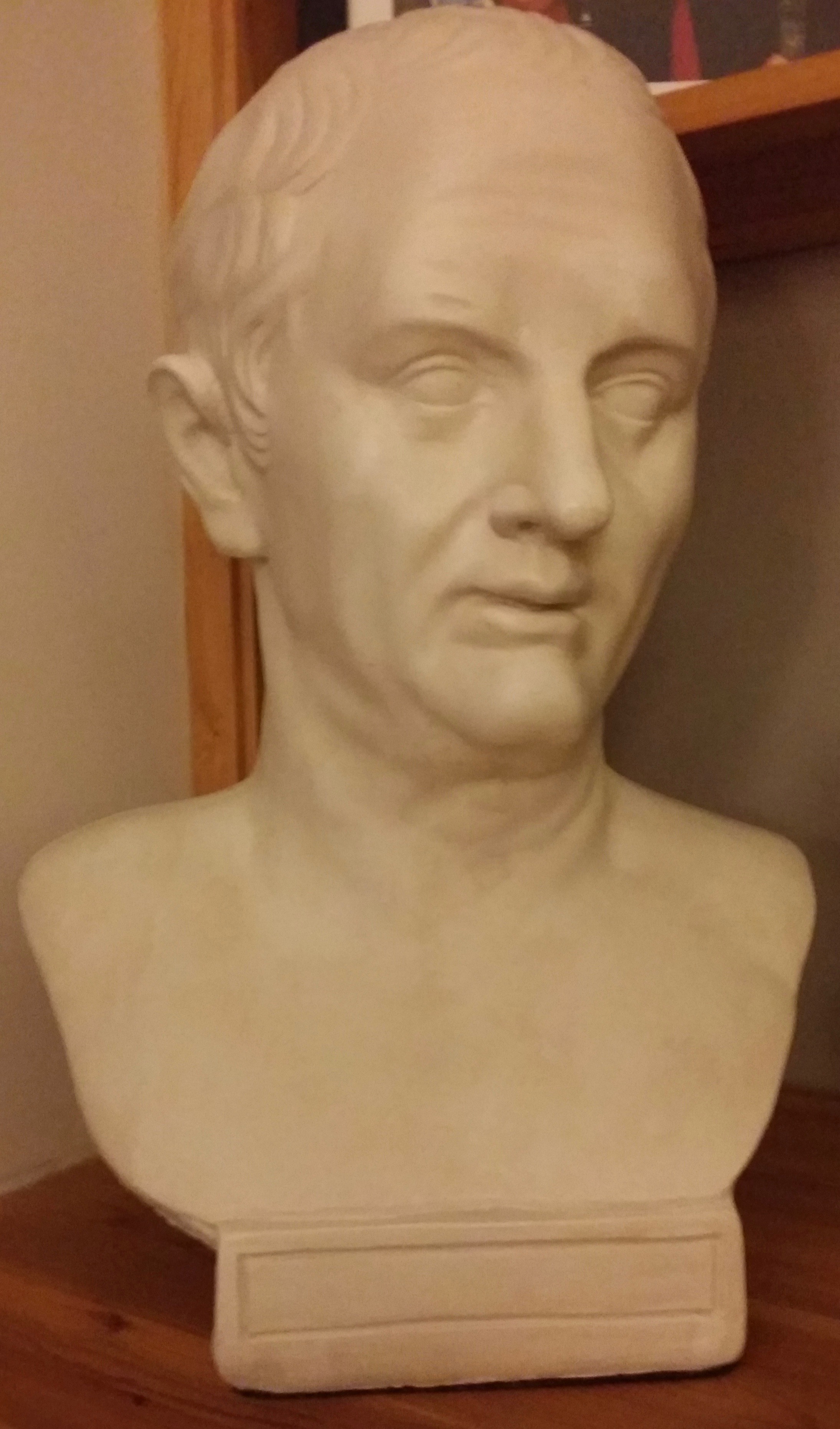

The ancient philosopher Cicero did much to cement the importance of virtue within the republican tradition. In his book De Officiis (On Duties) he took from Plato's Republic two crucial pieces of advice for those taking charge of public affairs: 'first to fix their gaze so firmly on what is beneficial to the citizens that whatever they do, they do with that in mind, forgetful of their own advantage. Secondly, let them care for the whole body of the republic rather than protect one part and neglect the rest' (Cicero, On Duties, ed. M. T. Griffin and E. M. Atkins, Cambridge, 1991, p. 33). Elsewhere in the work he voiced the idea that makes such behaviour seem impossible. Noting that, of the many fellowships that bind humans together, the most precious is the republic, he went on: 'What good man would hesitate to face death on her behalf, if it would do her a service?' (Cicero, On Duties, p. 23).

This idea that republican virtue requires the subordination of one's private interests to the public good, and that a good republican must be prepared to make immense sacrifices for the good of the whole, was reiterated in the eighteenth century. Perhaps the most powerful reflection of it is to be found in the art work of the French revolutionary painter Jacques-Louis David. His painting Brutus and the Lictors (1789) drew on a famous story from Roman history to explore the central themes of patriotism and the sacrifice of the individual for the good of the state. Lucius Junius Brutus, who had been responsible for expelling the Tarquins from Rome and thereby establishing the republic, discovered that his sons had been acting to restore the monarchy. He prioritised the good of the state over his own family by sentencing his sons to death for treason. While David's picture captures the enormous weight of Brutus's sacrifice, the message is clear that he made the right decision.

This understanding of 'virtue' is still in evidence today in the respect shown to veterans and their families. Moreover it is currently on display among those working in the NHS, care homes, supermarkets, and other essential services who are continuing to attend work despite the risks to their own health. Nevertheless few would welcome the notion, under normal circumstances, that civilian citizens should regularly be expected to put their lives or those of their family on the line for the public good.

I want to offer two thoughts in response to this myth. First that if we understand what is required in less extreme terms we can perhaps find some value in grounding our society more firmly in virtue - in a concern for the public good rather than mere private interests. Secondly, that some republican theorists were well aware that expecting human beings willingly to make huge sacrifices for the good of the public was unrealistic. They suggested, instead, that laws and systems of rewards and punishments could be used to create a situation in which people could be motivated by self-interested concerns to behave in a way that benefited the public as a whole. This approach might offer some possibilities for future policy.

To some degree those of us living in countries with a welfare state already accept the principle of sacrificing individual advantages for the good of the whole. The National Health Service in the UK, for example, is premised on the belief that free health care at the point of need is a public good and that individual citizens must sacrifice a portion of their income in order to pay for it. Similarly, here in the UK taxes ensure that free primary and secondary education is available to all children up to the age of 18, and this is paid for by all citizens regardless of whether they themselves have children, or indeed whether they choose to send their children to state schools.

We could extend this idea to other aspects of society. In an article that I linked to in last month's blogpost, George Monbiot argues that the choice we have to make is between 'public luxury for all, or private luxury for some'. He encourages us to imagine a society in which the rich sacrifice their private swimming pools and the middle class their private gym membership, reinvesting that money in high quality public sports facilities that are open to all. A society where a purpose-built public transport system provides swift, efficient, and comfortable travel for everyone, making it rational for individuals to leave their cars at home or abandon them altogether. One in which private gardens of varying sizes are exchanged for vast public parks complete with imaginatively thought out, well constructed, and properly maintained playgrounds that provide opportunities for all children to play and have fun, while in the process improving their health and wellbeing

Portrait of Pieter de la Court by Abraham Lambertsz van den Tempel (1667). Reproduced from Wikimedia Commons.

The problem is how we persuade people to make such sacrifices. We can find some answers by examining republican arguments of the past. While some republicans - particularly those of a strongly religious bent such as John Milton and Algernon Sidney - insisted on the need for genuine virtue on the part of rulers and citizens alike, others - including the Dutch thinkers Johann and Pieter de la Court, the Englishman James Harrington, the Frenchman the Abbé Mably, and the American John Adams - did not have such high expectations of the human capacity for virtue. They accepted that the majority of people would not be willing to make sacrifices for the public good unless it was clearly in their interests to do so. Consequently they argued that laws should be designed so as to direct people towards virtuous behaviour or that other incentives - such as honours and rewards - could be used to induce people to act in the public interest.

Harrington's whole constitutional system was designed with this end in mind. His most famous articulation of the argument was his story of two girls dividing a cake between them. If one girl cuts the cake, but the other gets first choice as to which piece she wants, the first girl will be led by her own self-interest (in this case understood as her desire to get the largest piece of cake) to divide the cake as evenly as she possibly can. Harrington used this as a metaphor for the organisation of legislative power within the state. He insisted on a bicameral legislature and argued that the upper house or senate should make legislative proposals, but the lower house should have the final say as to whether to accept or reject them. By this means the senate would be induced only to propose legislation that was in the public interest, since if they put forward measures in their own interests, the lower house would reject them.

Portrait of Gabriel Bonnet de Mably. Reproduced from Wikimedia Commons.

A different method was proposed by Mably. He insisted that human reason and virtue were too weak to act alone and that only a small proportion of people in any society would be capable of being led by reason at all times. Yet, he believed that even some of the strongest passions, if carefully orchestrated, could become virtues by being directed towards the public good. Offering rewards for public-spirited behaviour could ensure that ambition or the desire for fame and glory could be channelled towards positive ends. There is a close link between these methods and what modern behavioural scientists call nudge theory.

It would be naïve to think that society could be transformed overnight, but it would also be wrong to think that governments are impotent in these matters. Changes can be made by those courageous enough to do so. On 29 February 2020 the government of Luxembourg introduced free public transport across the entire country. In addition to seeing public transport as a public good, this is also a move designed to bring an even greater public benefit - that of improving the environment. There is evidence to suggest that this move alone may not be sufficient to encourage car users to make fewer journeys. But when pull factors - such as free public transport - are combined with push factors - an increase in parking fees, congestion charging, and increased fuel taxes - the desired outcome can perhaps be achieved. The pertinent question, then, is not whether citizens are virtuous enough to put the public good before their own private interests, but rather whether politicians are courageous enough to put in place the measures that would induce them to do this.

![John Lilburne, England's New Chains Discovered, London, 1649. http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/leveller-tracts-6. 18.10.17. Taken from the Online Library of Liberty [http://oll.liberty.org] hosted by Liberty Fund, Inc.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57a64976d1758e28c2a46317/1508942506653-MC9ZTGQZPUPJNO70AQAP/Englandsnewchains.png)