Republicanism is not a major political discourse in the UK today. In the recent parliamentary elections no candidate standing on the express ticket of republicanism was elected to power. Some might, therefore, conclude that my forthcoming book with Polity Press - Republicanism: An Introduction - is of merely academic interest. But, in fact, the arguments of the republican tradition are of direct relevance to us today, and their neglect has less to do with the ideas themselves than with the persistence of several common myths. The beginning of a New Year - and indeed a new decade - has prompted me to start a fresh series of posts which will explore these myths and suggest some lessons that might be learned from historical research on the republican ideas of the past.

In common parlance the very definition of a republic is that it is not a monarchy; so America and France are republics because both have a President as their head of state, whereas the United Kingdom and Holland are monarchies because their heads of state are a Queen and a King, respectively. Yet the differences between how these countries are actually governed on a day-to-day basis are relatively small. Moreover, the American President wields far more extensive powers, and is therefore closer to being a monarch, than the British or Dutch heads of state, and more power than these countries' Prime Ministers, who are more closely bound by their governments and parliaments.

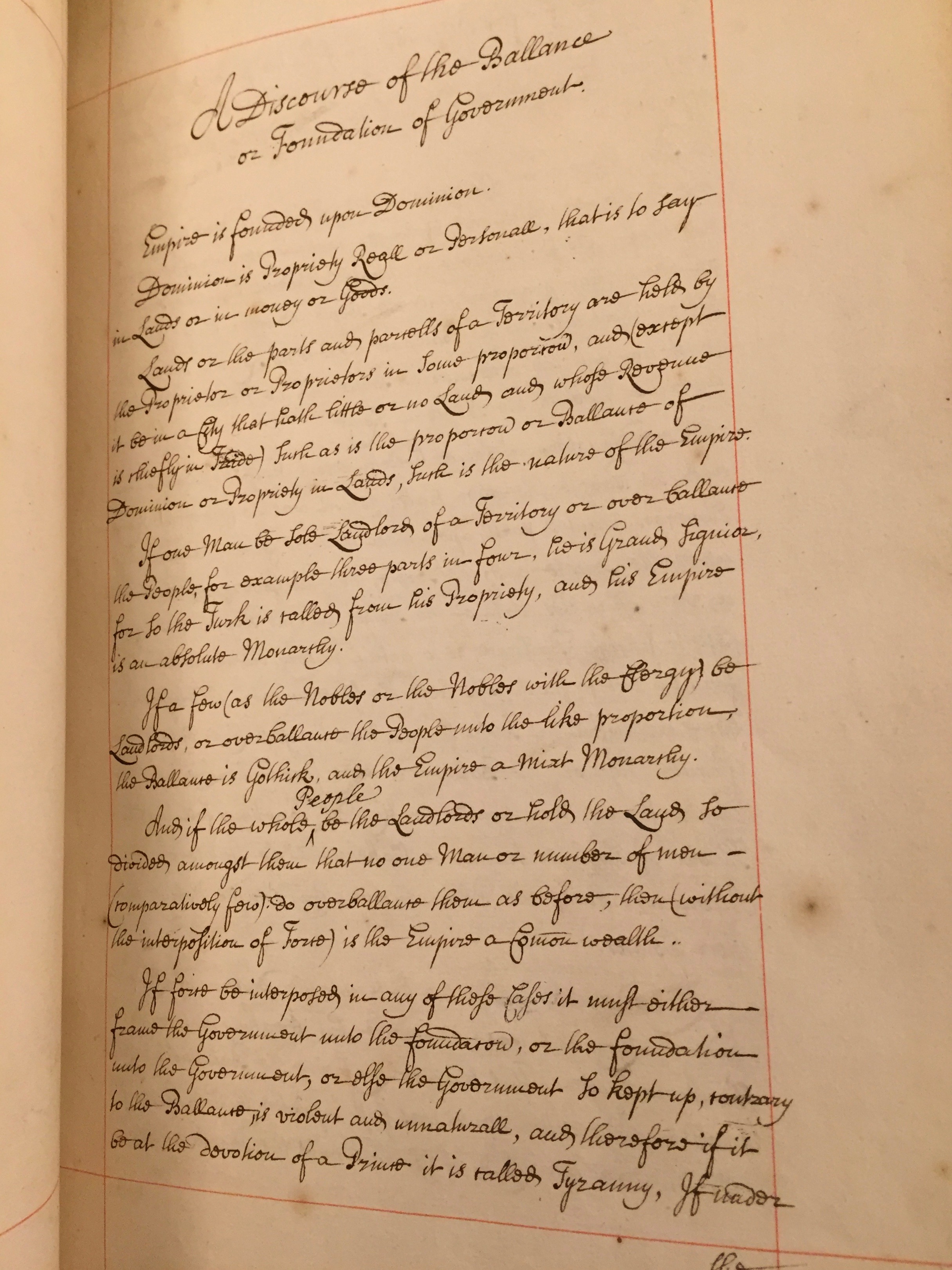

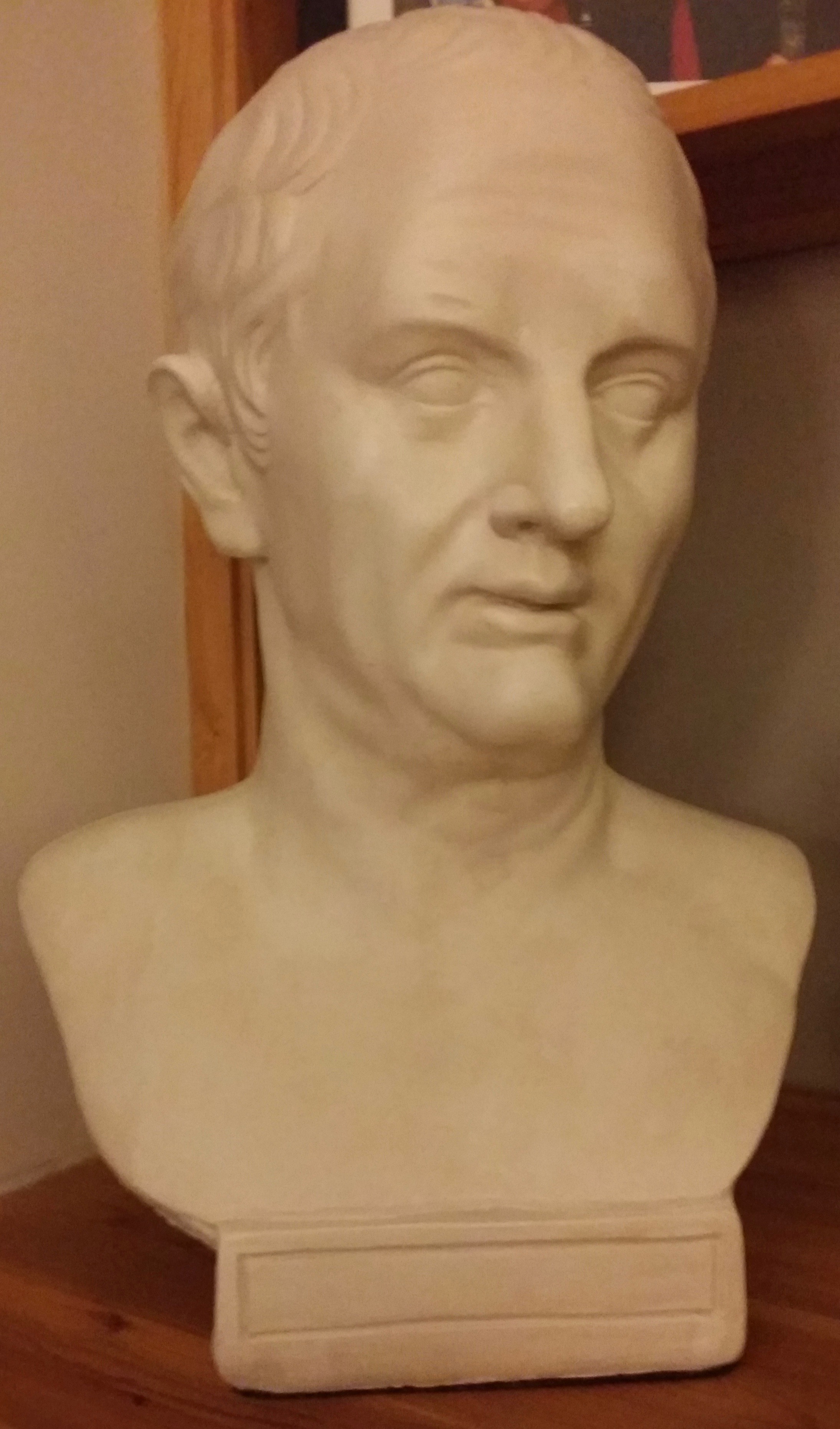

Bust of Cicero. Image courtesy of Dr Katie East.

This blurring of the distinction between republics and monarchies reflects the history of the terms. The original meaning of 'republic' did not contrast it with monarchy, that contrast gradually emerged between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries. Before that, republican government was simply understood as a form of rule that operated in the interests of the public or common good (res publica means public thing) rather than in the private interests of rulers. This understanding was reflected in the Roman statesman and political writer Cicero's claim in De Republica 'That a commonwealth [republic] (that is the concern of the people) then truly exists when its affairs are conducted well and justly, whether by a single king, or by a few aristocrats, or by the people as a whole'. (Cicero, On the Commonwealth and On the Laws, ed. James E. G. Zetzel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 59). For Cicero, republican government was simply good government, and monarchies could not meet this requirement.

Ironically, given their current political systems, the Dutch and the English were at the forefront of overturning this definition, making anti-monarchism the touchstone of republican rule. The Dutch were unusual among sixteenth-century republicans in their insistence that anti-monarchism is a crucial component of republicanism. Similarly, it was in England in the mid-seventeenth century that practical expression was given to the idea that only a government that is grounded in the will of the people can be legitimate and that, therefore, all forms of non-elective monarchy and hereditary political privilege had to be rejected.

The Execution of Charles I. Reproduced from Wikimedia Commons.

Today, attacks on the monarchy tend to focus on its public funding, which in the UK operates via the Sovereign Grant, or on scandals involving members of the royal family - such as the recent debacle over Prince Andrew's involvement with Jeffrey Epstein. While royal scandals are certainly embarrassing for us as a nation, they do not directly threaten the government of the country. By comparison, the question of whether the state is being run in the public interest (including the uses to which public expenditure is put) is far more pertinent. On this question, so-called republics are as much at risk as monarchies. On 4 December 2019 the House Intelligence Committee of the US Congress approved an impeachment report against President Trump. In that report Trump is accused of abusing his power for personal gain by pressuring Ukraine to investigate his political rivals and obstructing Congress's investigation into his actions: the President is being accused of putting his own private interests before the public good.

Of course, there are some fundamental questions lying beneath the older interpretation of republican government: What exactly is the public interest? How could it be rationally determined? Is the public interest the same as what is in the interests of the majority? Does this mean that the interests of minorities can be ignored? Is the public interest merely what is expedient, or does it take account of principles that are held to define the character of the nation; or perhaps ones that are universal in character - as the French would certainly claim in their case? There are no easy answers to these questions, but they need to be given a great deal more attention than they currently are if the UK and other countries today are to become genuine republics. From this point of view, what we do about the royal family is a sideshow

![John Lilburne, England's New Chains Discovered, London, 1649. http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/leveller-tracts-6. 18.10.17. Taken from the Online Library of Liberty [http://oll.liberty.org] hosted by Liberty Fund, Inc.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57a64976d1758e28c2a46317/1508942506653-MC9ZTGQZPUPJNO70AQAP/Englandsnewchains.png)