Having just returned from a fascinating conference at the European University Institute (EUI) near Florence I feel I must interrupt my series of posts on Republicanism to offer some reflections on that event.

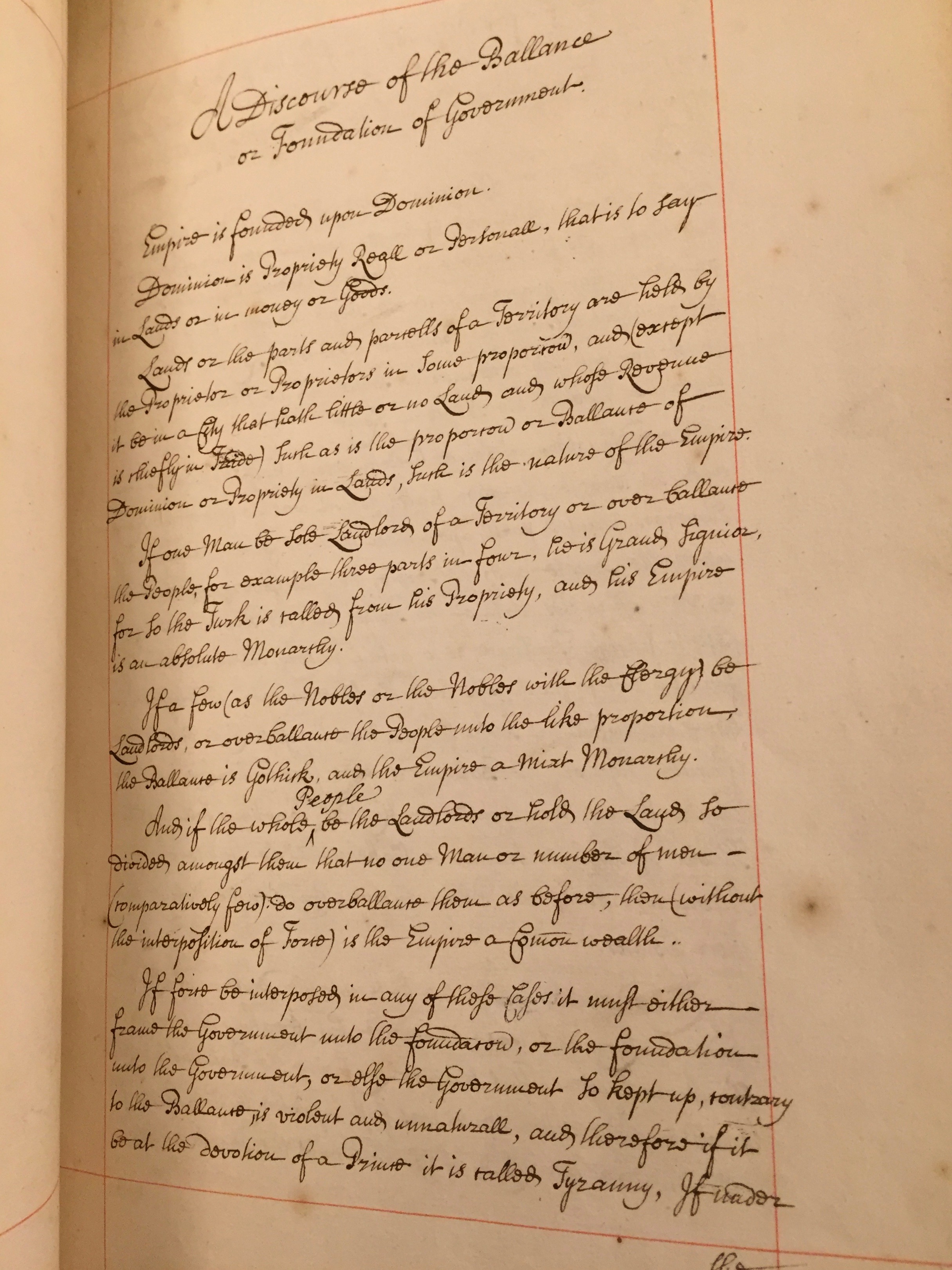

Villa Salviati. Image by Rachel Hammersley.

The conference was expertly organised by four PhD students based at the EUI: Thomas Ashby, Ela Bozok, Muireann McCann and Elisavet Papalexopoulou. It was held in the beautiful Villa Salviati. Medici imagery appears throughout the villa in reference to the family link via Lucrezia, the wife of Jacoo di Giovanni Salviati who owned the villa in the sixteenth century and whose renovations determined the current layout. Contributors to the conference were lucky enough to be shown the private chapel that Jacopo constructed, probably for his daughter's wedding, with its beautifully decorated ceiling bearing heraldic devices alluding to the alliance between the Medici and Salviati families.

The ceiling of the private chapel at Villa Salviati. Image by Rachel Hammersley.

The conference theme, 'transcultural conversations', is not only academically popular at present (as evidenced by the excellent papers), but also has potential contemporary relevance. My own work in this area has tended to focus on the crossing of linguistic boundaries particularly through translations. In my paper I reflected on this work arguing that to fully understand the impact of translations we need to go beyond the conventional texts to look not only at explicit and acknowledged translations, but also at works that perform similar functions; to consider the form and materiality as well as the content of the text; and to look at the uses to which translations and associated texts were put. The conference organisers and participants very deliberately chose the term 'transcultural' rather than 'transnational' and took a broad approach.

Some papers did consider conversations that took place across national and linguistic boundaries - for example Arnab Dutta's paper on discussions between Bengali and German scholars and intellectuals in the 1920s and 30s over the meaning of the term 'kultur' and Simone Muraca's paper on cultural diplomacy between Italy and Portugal in the same period. Others considered conversations that occurred across confessional divides. Thomas Pritchard's paper on pan-European Anti-Spanish polemic highlighted the distinction between Anti-Catholic and specifically Anti-Spanish arguments. Concerns about the establishment of a Spanish universal monarchy were articulated not just by Protestant authors but also by Catholics such as Trajano Boccalini and Paolo Sarpi, whose works were then translated into English and used to further English campaigns. Such conversations could even cross the religious/secular divide as Agathe de Margerie's paper on the Austrian Paulus Gesellschaft made clear. She showed how in the late 1960s attempts were made by the group to open up a dialogue between Catholic and Marxist thinkers and the ideologies they embraced. Other papers explored conversations across philosophical boundaries, as in Nicholas Devlin's paper on 'The continental Marxist origins of American totalitarian theory' and Luke Illott's paper exploring Michel Foucault's crossing of the boundary between the English and Continental philosophical traditions. Moreover, Benjamin Thomas, in his paper 'Intra-Party Contestation: Ideological Transformations and Neoliberalism', emphasised the importance of considering conversations within, as well as between, ideological groups. In a number of these cases, conversations took place across multiple cultural boundaries simultaneously.

The means by or through which these conversations occurred were equally complex. While some participants focused on the reading, translation, and writing of published texts, others engaged with conversations that took place in private correspondence or even face-to-face. Thus, the kind of 'conversation' that Hugo Bonin explored in his paper on Henry Reeve's English translation of Alexis de Tocqueville's Democracy in America, and the British reception of the work that resulted from it, was very different from the face-to-face encounters discussed by Dutta's Indian and German intellectuals or de Margerie's Marxists and Catholics. In both types of conversation, however, it was noted that the engagement could be either monolingual or multilingual (the conversations Dutta described took place in English, French, and German as well as in various Indian languages).

Alex Collins's paper looked more theoretically at methods of communication. He argued that the pioneering seventeenth-century scientist Henry Oldenburg expressed an explicit preference for knowledge gained via acquaintance (for example news that came directly from his contacts) as compared with knowledge by description (such as the information he might gain from newspapers). For Oldenburg the advantage lay primarily in the importance of trust in knowledge formation. In our discussion, however, we also considered the fact that direct engagement between people tends to encourage cultural conversations that are multi-directional rather than ones in which ideas flow in only one direction.

Portrait of Henry Oldenburg, attributed to Jan van Cleve. Reproduced from Wikimedia Commons.

All of this complexity inevitably generates obstacles to communication. These might include problems of vocabulary and language. Dutta noted that initially there was no Bengali word for kultur, it simply had to be transliterated from the German. But there was another word from the west of India, 'Sanskrita', the etymology of which derived from the notion of krishe/krishti or cultivated ground, which brought fresh connotations to the Indian version of the kultur/civilisation debate. Similarly, Bonin noted that 'democracy' had different connotations in English from how the word was used in French. For British readers it still tended to be understood to refer to a type of regime, whereas in Tocqueville's French account it had a broader meaning, referring to a relatively egalitarian form of society.

One way around obstacles to communication is to use different formats for the transmission of ideas. This was a particular focus of Panel 2 'Transfer through print, visual arts and music'. As Lia Brazil demonstrated, English pamphlets engaging with the South African War took very different forms, with the strong graphics and poetry of the Stop the War Committee publications contrasting starkly with the much more plain, cautious approach of those produced by the South African Conciliation Committee. Here, form was probably designed to mirror content, with the Conciliation Committee publications engaging in much deeper legal and philosophical debate, which Brazil expertly analysed. Arthur Duhé focused to an even greater degree on form in his paper 'Affective transfer in revolutionary times'. He noted how engravings and songs were used to convey the emotional aspect of the 1848 revolutions - and particularly the impact of the deaths of revolutionary martyrs - to foreign audiences. Duhé argued persuasively that historians of revolutions need to pay more attention to visual and musical sources, their production and material transfers. In a later panel Jessica Sequeira picked up this theme. Her protagonists - Pedro Prado and Antonio Castro Leal - did not merely translate poetry, but actually went so far as to invent an Afghan poet Karez-i-Roshan. As Sequeira argued, this playfulness was not simply a prank or joke, but had a deeper meaning and resonance as a deliberate method of enacting a transcultural conversation.

Il Duomo. Image by Rachel Hammersley.

Other contributors explored other means by which different communities could dialogue with each other when holding conflicting views and opinions. Luke Illot made a strong case for the fact that it was Foucault's reading of the Oxford Analytic philosophers - and the conception of language that he derived from that reading - that provided a basis on which he could open a dialogue between the English and Continental philosophical traditions, one which had seemed impossible at the time of the Royaumont Conference in 1958. Highlighting the contingency that often facilitates or frustrates these conversations, Illot noted that it was in Tunisia, and via the library of Daniel Defert, that Foucault gained access to these ideas. Similarly, Anna Adorjána referred in her paper 'Conceptualising and experiencing (inter) nationalism. The Case of the Social Democratic Party of Hungary in 1903' to Martin Fuchs's concept of the 'third idiom'. This is an overarching or higher level discourse that provides space for communication in a conflicted situation. In the case of the Hungarian Social Democrats, international class struggle performed this role, but in cases discussed by other participants human rights or religion enacted a similar function.

Yesterday's 'Brexit Day' reflects the huge political and ideological divisions that not only affect Britain's relations with the rest of Europe but also run right through the UK itself. Now, more than ever, it would seem we need to find ways to engage in positive and constructive transcultural conversations. The diverse and myriad ways in which such conversations have taken place across more than five centuries is perhaps grounds for some small hope and optimism.