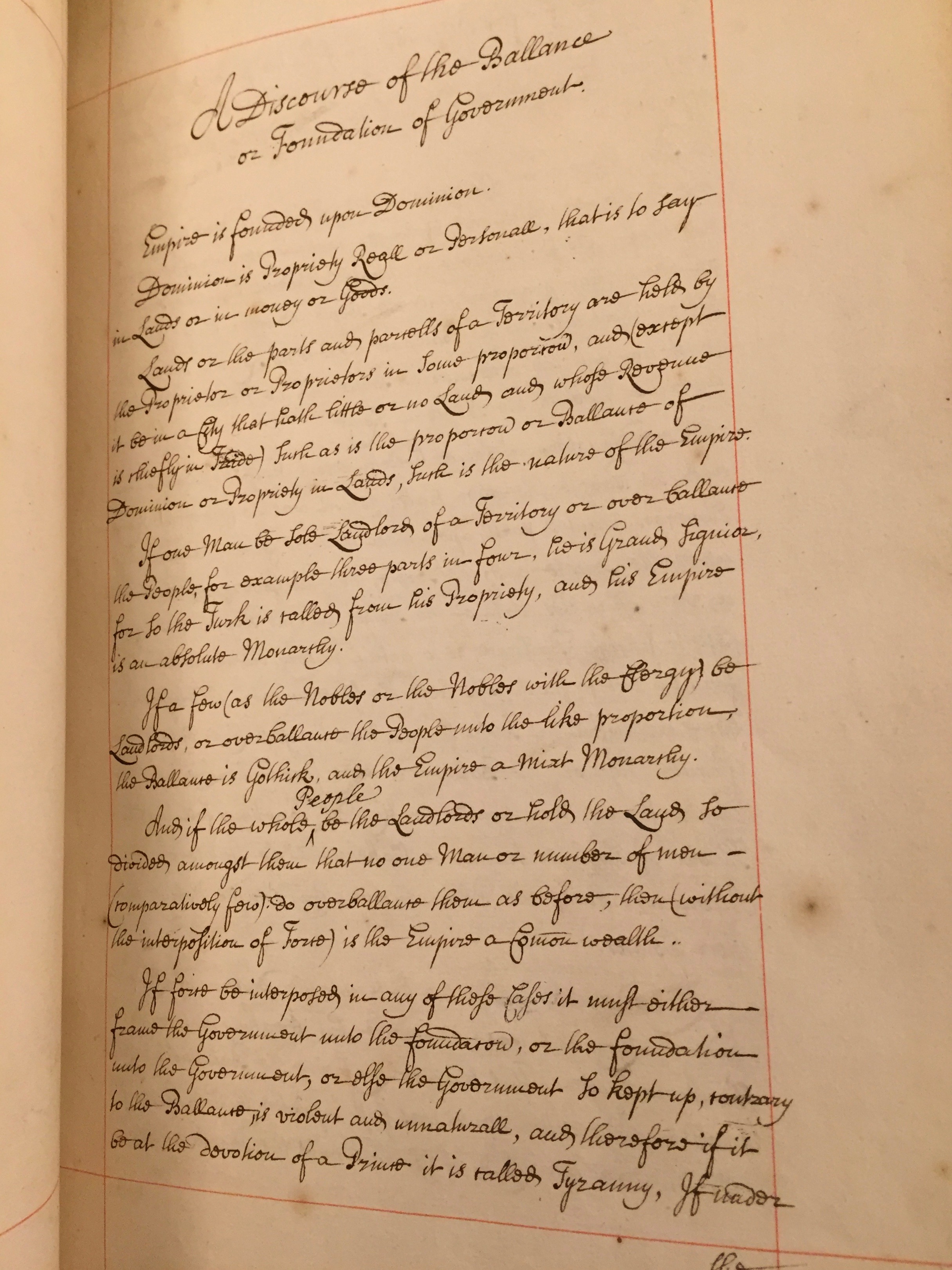

‘A Discourse of the Ballance or Foundation of Government’. Reprinted with permission @British Library Board, Harleian MS 5063 f.17.

Manuscripts not only have the potential to reveal hidden facts about their authors and the purpose behind, or gestation of, their works - as explored in my previous blogposts - but they can also sometimes reveal crucial information regarding the reception of ideas. In the 1960s a manuscript text entitled 'A Discourse of the Ballance or Foundation of Government' was discovered, which was at first believed to have been an early draft by James Harrington of part of The Commonwealth of Oceana. In initial analyses, the fact that the phrase 'the late monarchy' was rendered 'this monarchy' was taken as evidence that the draft dated from before the regicide, so that Harrington was, therefore, already voicing republican ideas during the 1640s.

These assumptions were convincingly disproved by Andrew Sharp in 1973. (A. Sharp, 'The Manuscript Versions of Harrington's Oceana', The Historical Journal, 16:2 (1973), pp. 227-39). He provided compelling evidence that 'A Discourse' actually postdated Oceana, and constituted a handwritten copy of passages from the printed text rather than an early draft of it. Yet he rightly insisted that this did not diminish the significance of the document, since it shed light on the domestication of Harrington's ideas, revealing how 'Harrington, a supporter of revolution, was made a conservative'. (Sharp, p. 227). 'A Discourse' used Harrington's theory of the balance of property - and his account of changes in that balance in England over the previous century - not, as Harrington himself had done, to advocate the replacement of traditional monarchy with popular government, but rather to call for a redressing of the balance among the institutions of England's mixed monarchy and in particular to defend the place of the nobility within that system.

‘A Discourse of the Ballance or Foundation of Government’. Reprinted with permission @British Library Board, Sloane MS 3828 f.75.

Since the initial discovery, two further versions of 'A Discourse' have been found. All three appear in manuscript volumes comprised of slightly different compilations of extracts from various seventeenth-century texts (Bodleian MS Eng. Misc. C. 144, ff. 110-23; British Library Sloane MS. 3828, ff. 75-80v and Harleian MS 5063, ff. 17v-11 pagination reversed). While the texts included in the volumes are quite diverse, Harrington's theory of property does appear to have been a common theme since also included in the Bodleian and Sloane volumes is A Letter to Monsieur Van B de M at Amsterdam, by the Presbyterian MP Denzil Holles, which includes the statement: 'the Ballance of Lands is the Ballance of the Government' and draws similar conclusions to 'A Discourse' from this theory for English society.

Sir Robert Southwell by John Smith, after Sir Godfrey Kneller, Bt, mezzotint, 1704. Reproduced under a creative commons license from the National Portrait Gallery, NPG D31190.

What, then, were the contexts in which these volumes were produced? We can start with their owners. The Bodleian volume was owned by Robert Southwell (1635-1702), an Irish-born MP, statesman and diplomat in the Restoration regime. One of the British Library volumes was owned by Sir Hans Sloane, an Irish physician, naturalist and collector who was important in the establishment of the British Museum. The other British Library version is part of the Harleian collection, bequeathed by Robert Harley (1661-1724).

Henry Oldenburg’s notes on Harrington’s The Commonwealth of Oceana. Royal Society MS 1 f.90. I am grateful to Katherine Marshall for copying this manuscript and for permission to reproduce the image here.

What appears to unite two, if not all three, of these figures is the Royal Society. Southwell was admitted as a fellow in 1662, and was an active participant for the rest of the century, even serving as president between 1690 and 1695. Sloane, who was much younger than Southwell, was not admitted until 1685, but he too was active and was secretary from 1693-1700. Robert Harley was proposed, though not elected as a member of the Royal Society, but relations of his, including his father Edward Harley (1624-1700), were fellows, though they appear to have been much less active than Southwell and Sloane (Michael Hunter, The Royal Society and its Fellows 1660-1700, The British Society for the History of Science, 1982). Another fellow Abraham Hill - who was treasurer between 1679 and 1699 - was also closely associated with the volumes. He was identified as the person who had extracted and copied 'Mr Hooker's Opinion of Government' in the Bodleian volume, and a letter written to him by another Royal Society fellow William Petty, was also included in that volume. Petty died in 1687, so he was no longer active in the Royal Society in the early 1690s when Southwell was president, Sloane secretary and Hill treasurer, but he had been a good friend of both Hill and Southwell, and the three of them had collaborated closely within the Society in the early 1670s, when they had all been council members. Yet another council member at that time also displayed an interest in Harrington. The natural philosopher Henry Oldenburg was a salaried secretary of the Society for a time. Among his papers is his transcript of part of the preliminaries of Oceana.

Sir William Petty by Isaac Fuller, oil on canvas, c.1651. Reproduced under a creative commons license from the National Portrait Gallery, NPG 2924.

It was Petty, though, who provided a direct connection back to Harrington having been a regular attendee at the Rota Club and, according to Aubrey, 'trouble[d] Mr Harrington with his arithmetical proportions and ability to reduce politics to numbers'. (John Aubrey, Brief Lives, ed. Kate Bennett, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015, I, p. 232). Petty also picked up on the term 'political anatomy' which Harrington had coined, calling one of his works The Political Anatomy of Ireland. Further evidence of Petty's interest in key aspects of Harrington's theories is suggested by a manuscript, again in the British Library, in which Petty challenged Hobbes's defence of monarchy, and advocated a democratic system which adopted a similar division of the population to that proposed by Harrington in Oceana (Frank Amati and Tony Aspromourgos, 'Petty Contra Hobbes: A Previously Untranslated Manuscript', Journal of the History of Ideas, 46:1, 1985, pp. 127-32). Harrington and Petty evidently remained in contact with each other for the rest of Harrington's life, since there is a letter from Harrington to Petty dated 1676, again in the British Library. The letter follows up a request Harrington claimed to have made previously that the Royal Society provide a suitable place and instruments for the performance of an experiment which Harrington rather pompously claimed was 'more intimately concerning the good of man kind than any other hitherto contained in the writings or known experience of any of the Philosophers' (British Library: Petty Papers h.f.33).

In his 1973 article, Sharp suggested that an original version of 'A Discourse' was probably produced in the 1670s, and that the manuscript volumes were probably gathered together in the 1690s. The Royal Society link offers some explanation for this history. It seems likely that Petty inspired interest in Harrington among members of the Royal Society in the 1670s. This was a time when Petty and others were seeking to expand the appeal of the Society and reverse the decline in membership (Hunter, The Royal Society). Perhaps extending the Society's interests into economic and political matters, a field in which Petty was himself interested, formed part of that campaign. Moreover, the conclusions drawn from Harrington's theory were also timely, given the political situation - especially the worry among Whigs that the English constitution was being threatened by the encroaching absolutism of Charles II, and the fear of even greater future encroachment under his brother James. In the 1690s, when the question of the encroachment of royal power was again an issue, due to the controversy about William III's attempt to maintain a standing army in the aftermath of the Treaty of Ryswick, Harrington's theory would again have appeared relevant to present politics. It was perhaps this that prompted Southwell, Hill and Sloane to include 'A Discourse' in the manuscript volumes they were involved in putting together. There is a twist, however, since - with Petty now dead - the link back to Harrington appears to have been lost. Harrington's authorship of 'A Discourse' is not mentioned in the volumes, indeed in Southwell's copy a handwritten note attributes it to the English antiquary Sir Henry Spelman.