The exhibition poster. Image by Rachel Hammersley.

On 8th December 2023 the exhibition 'Encountering Political Texts 1640-1770' - the final event of the Experiencing Political Texts project - opened at the National Library of Scotland. I offered an appetiser for the exhibition in my last blogpost by discussing the various books bound by Thomas Hollis that were donated to the Advocates Library in Edinburgh, some of which appear in the exhibition. This month I offer a taste of some of the other items on display - focusing on the themes of materiality, genre and the debating of issues in print.

Materiality

Opening graphics on the wall of the exhibition. Image by Rachel Hammersley

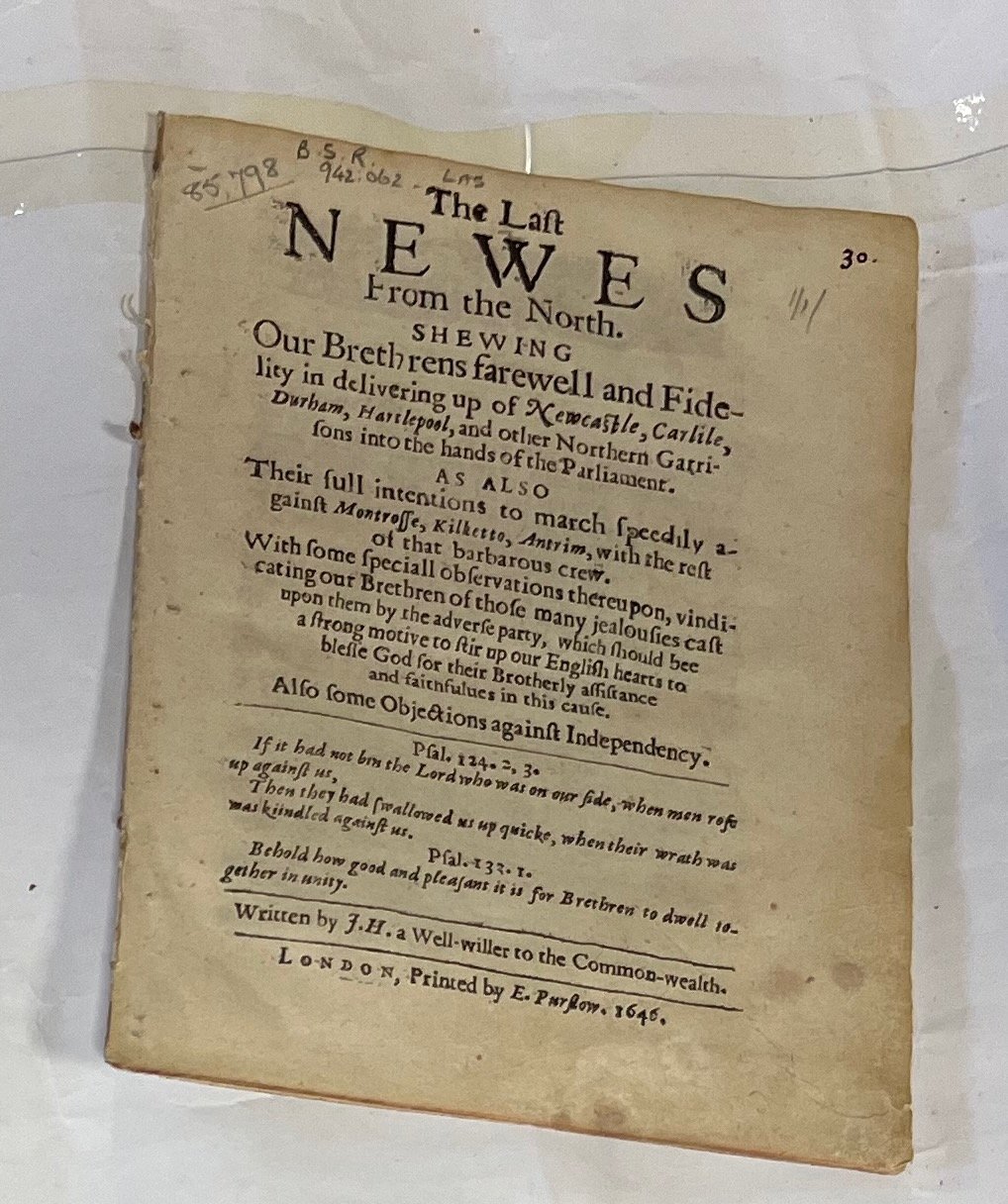

The Hollis editions are interesting because of their elaborate bindings and handwritten marginalia, which reflect Hollis's own reading of the texts. Other items on display in the exhibition also reflect the importance of texts as material objects. At the other end of the spectrum from the lavish Hollis volumes are the examples of unbound pamphlets. Reading 'original' pamphlets today generally involves going to a Special Collections reading room and identifying the pamphlet within a volume of such material that was bound together in book form at a later point in time. This experience of encountering early modern pamphlets is very different from that of their original readers. Pamphlets would have been sold on the streets by hawkers. They will have varied in size and quality, but many will have consisted of just a few pages of text printed on flimsy paper, their ephemerality reflecting the fact that they were often interventions in specific (and sometimes fleeting) events - a bit like a social media post today. They were not really intended to last - and it is important that we remember this when reading them.

Other material from the seventeenth century takes a more elaborate physical form. A prime example here are the three volumes of Eikon Basilike that appear in the exhibition. This important work was published in the immediate aftermath of the execution of Charles I in January 1649. Said to be based on Charles's own thoughts and writings during his imprisonment, this was a powerful work which sought to transform the failed king, who had been executed by some of his subjects, into a martyr worthy of veneration. The frontispiece image reflects this aim in its depiction of Charles discarding his earthly crown and seeking instead the heavenly crown of martyrdom. (A more detailed analysis of the image is available here). I have seen at least one version of this image that has been hand-coloured, with the King's robe light pink and his sleeves a deeper maroon. (In fact, the striking pink colour scheme of our project - which is reflected in the NLS exhibition - was inspired by this). While the version of the image in our exhibition is in black and white, the title page of the work, which is also on display, includes red ink, which was more costly to produce and so again an indicator of quality. The NLS also holds a small version of Eikon Basilike which has an embroidered cover. Whereas the red type was the work of the printer, this cover was probably produced by the owner of the work, reflecting its importance and significance to them.

Infographic produced by Nifty Fox reflecting the reading group discussion on ‘Books as Physical Objects’ as displayed in the Encountering Political Texts exhibition. Image by Rachel Hammersley

This beautiful little book reminded me of the Reading Group session we held earlier in 2023, to which each member brought a book that was special to them. One participant bought along a book with a handmade cover, like the copy of Eikon Basilike on display. Others had marginalia or material pasted or tipped in by the owner - and again we have an example of this in the exhibition. One of several pamphlets on display that engages with the debate over the union between England and Scotland in 1707, Parainesis Pacifica; or, A perswasive to the union of Britain has a letter tipped in at the back.

Genres

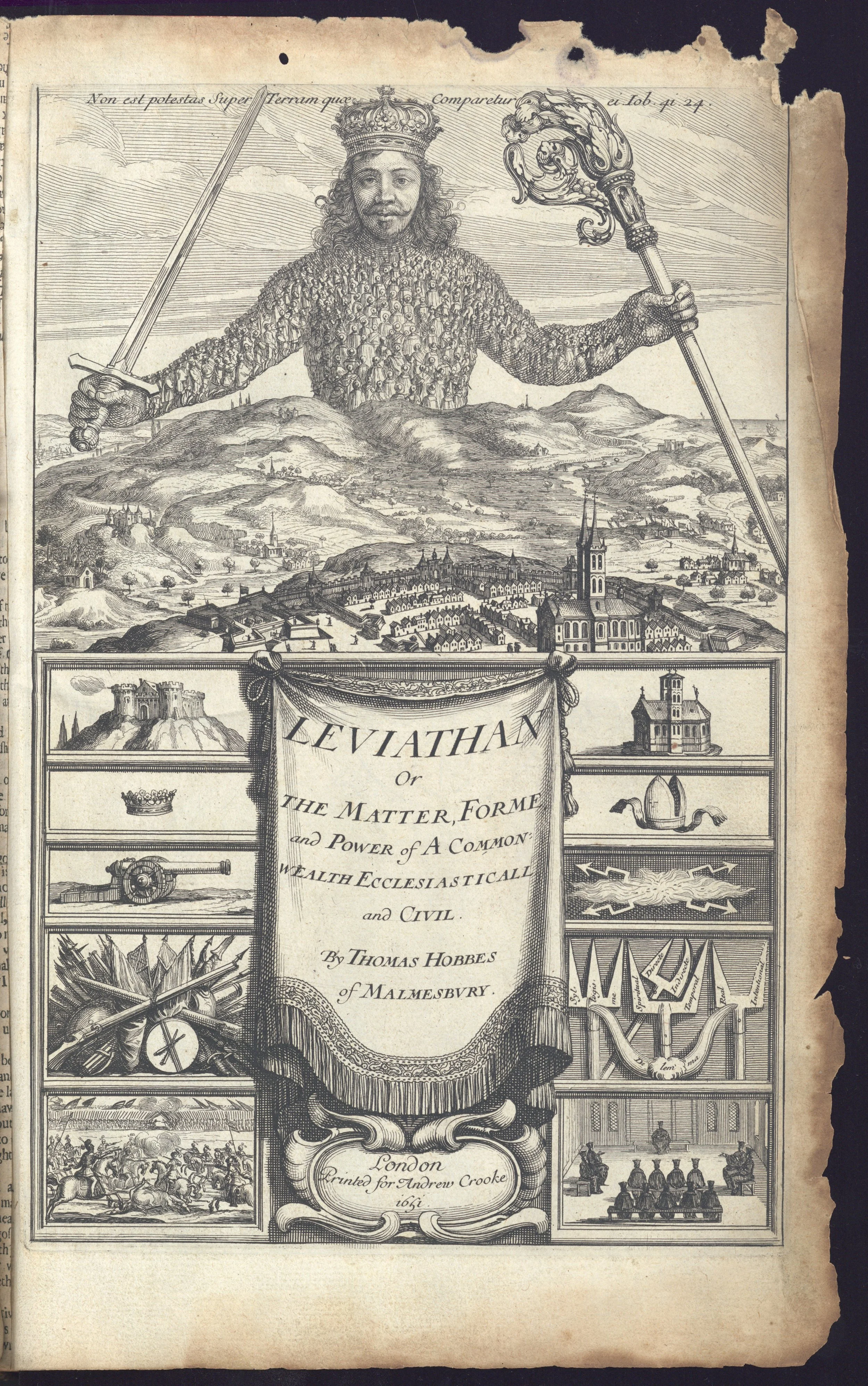

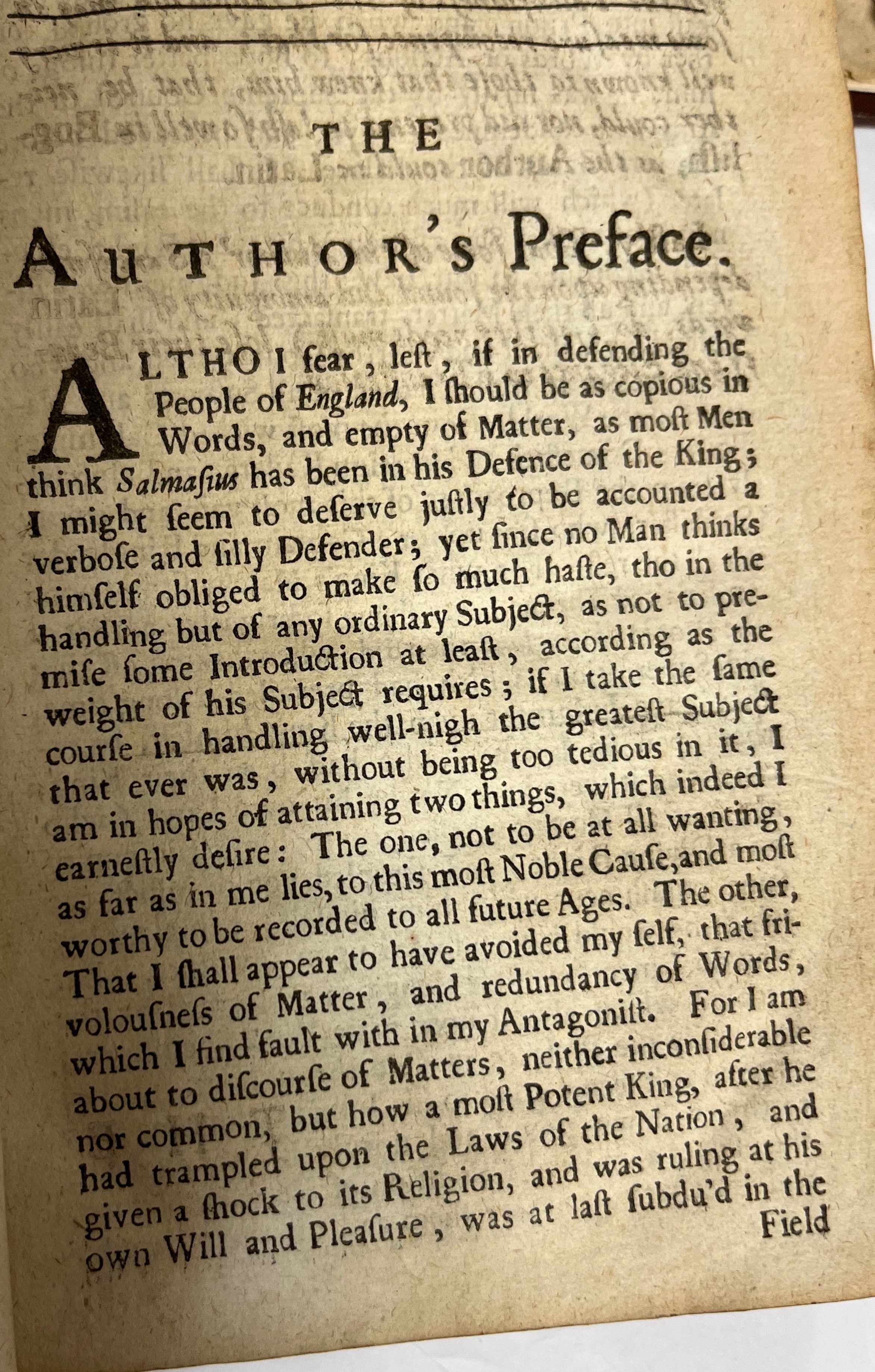

Another theme of our project that is reflected in the exhibition is the variety of genres used to convey political ideas. While pamphlets that engaged directly with contemporary debates, and presented the argument or viewpoint of the author, were common at this time, political ideas could also be conveyed through texts originally intended for oral delivery, such as proclamations and sermons (which would be preached from the pulpit and then printed). We have a number of these relating to the Union debate on display in the exhibition. Fictional forms such as utopias, invented travel narratives, and imagined dialogues were also popular ways of conveying political ideas in the early modern period. In addition, humour could be deployed to convey an argument in a more forceful way, as in the case of The comical history of the mariage betwixt Fergusia and Heptarchus - a humorous take on the union debate - which is included in the exhibition.

For many years newspapers were a key vehicle for transmitting up-to-date political news and information. At the present time when these are shifting online and are at risk of being overshadowed as a news source by social media, it is interesting to look back to their origins. While newspapers as we know them are generally seen as emerging in the eighteenth century, the mid-seventeenth-century crisis in the British Isles prompted the publication of newsbooks which served a similar purpose. Like modern newspapers they took different political stances (there were both royalist and parliamentarian newsbooks) and often included an editorial as a preface to the account of current affairs. At the NLS exhibition there are examples of several seventeenth-century newsbooks including Mercurius Politicus, Mercurius Britanicus, and The Publick Intelligencer.

Debates in Print.

Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun, by Andrew Birrell, published by Robert Wilkinson, after William Aikman, line engraving, 1798. National Portrait Gallery NPG D30937. Produced under a Creative Commons Licence.

As well as conveying and spreading knowledge of recent events, print could also be the site for political debate. The Union debate in the early eighteenth century generated a huge amount of printed material. Various examples are on display in the exhibition (some of which have already been mentioned). Sometimes individual authors would produce multiple responses and counter-responses to each other in print. In the exhibition are pamphlets attributed to Andrew Fletcher and James Webster produced in 1706-7. The initial pamphlet attributed to Fletcher did not explicitly oppose the idea of union, but suggested that a more equal union would be secured if each nation retained its own Parliament. On the other side, Webster, a Presbyterian minister who had previously been imprisoned for his religious opinions, argued against union on any terms, largely because of the impact it would have on the Scottish Kirk. Reading all the pamphlets in the debate gives a sense of how it unfolded and the different views it generated. We have to be careful too about authorship. Recent scholarship, as reflected in the article on Fletcher in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, suggests that although the pamphlet State of the Controversy betwixt United and Separate Parliaments was attributed to Fletcher, it was probably not written by him (John Robertson, 'Fletcher, Andrew, of Saltoun (1653?-1716)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography).

While this exhibition is the final element of our Experiencing Political Texts project, this first blogpost of the year is an opportunity to look forward as well as backward. We are already planning to explore the themes of the exhibition with audiences in Edinburgh at two workshops linked to the exhibition that will be held on Tuesday 27 February and Tuesday 9 April 2024. It should be possible to sign up for these events via Eventbrite soon. In addition, we are already exploring how we can develop the ideas generated by the Experiencing Political Texts project in a new project focusing on Political Education. We are holding an initial exploratory workshop for this project in Newcastle on 17 January 2024. I hope to provide further updates as the year progresses.