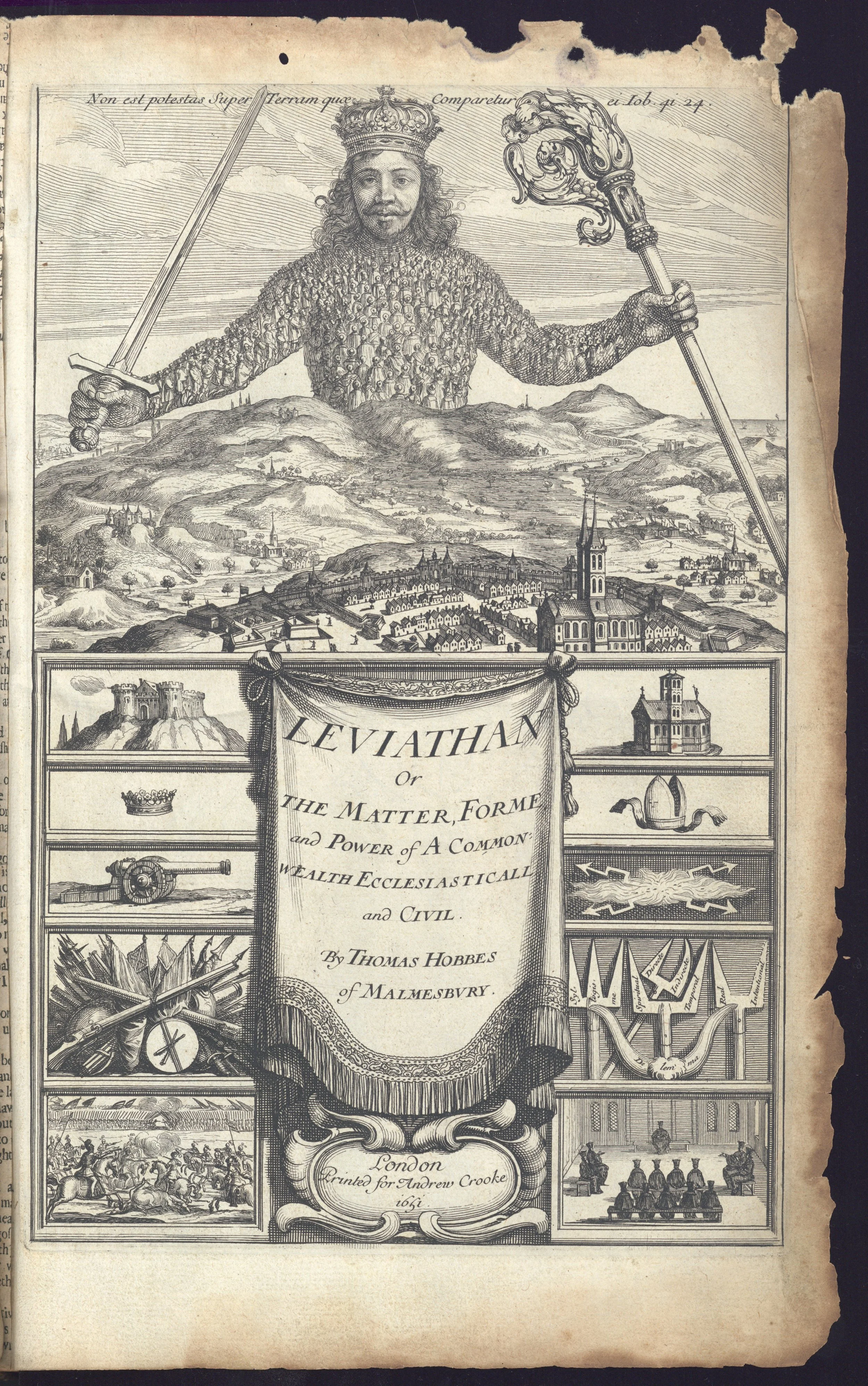

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (London, 1651). Philip Robinson Library, Newcastle University Special Collections (Bainbrigg, Bai 1651 HOB). Reproduced with permission.

This month I've been teaching my British Revolution students about the political thought of the period - including that of Thomas Hobbes. I use the frontispiece to Hobbes's Leviathan as a means of allowing the students to work out the key arguments of that text for themselves. The figure rising out of the sea always generates interesting discussion. Is it Charles I? Oliver Cromwell? They always seem disappointed when I explain that it is the embodiment of the state. The fact that the scales on the figure's body are little people also prompts debate. The significance of the objects the figure is holding, and their relationship to the two columns on either side of the bottom half of the image, are usually easier for the students to decipher. The sword in the figure's right hand represents civil power and corresponds to the five images on the left: a castle or fortification, a crown, a cannon, a battle, and a battlefield. The crozier in the figure's left hand symbolises ecclesiastical or religious power and beneath it are images reflecting the religious equivalents of those on the left: a cathedral, a bishop's mitre, divine judgement, theological disputation, and convocation. Hobbes's point, as my students quickly discern, is that the state should command both civil and religious power within the realm, and therefore should dictate the laws and the form of religious worship. For Hobbes this imposition of clear rules from above was the only way to prevent the chaos and destruction of civil war.

In this way, the frontispiece offers a visual depiction of the idea of civil religion. This is the topic of a collection of essays entitled Civil Religion in the Early Modern Anglophone World, 1550-1700, due out later this month, which I have edited together with my colleague Adam Morton. The book, and a special issue of the journal Intellectual History Review edited by Katie East and Delphine Doucet, are the main outputs of a project that dates back to 2016. In September of that year we established a small reading group involving staff and postgraduate students. We met regularly for about two years discussing texts ranging from Strabo's Geography to Ethan Shagan's The Rule of Moderation, with the aim of coming to a deeper understanding of the slippery concept of civil religion - particularly in an early modern context. We held a workshop with various invited speakers in September 2017 and hosted several guest speakers at our reading group. Finally, in October 2019 we held a conference 'Civil Religion From Antiquity to the Enlightenment' which we coupled with a public facing event at Newcastle's Literary and Philosophical Society on the theme of 'Politics and Religion: Past and Present'. It is papers from the conference which have been revised for publication in our book and the journal special issue.

The book focuses on the English-speaking world in the period between the mid-sixteenth and the end of the seventeenth century. It argues that this period - and more specifically issues raised then by the Reformation and the British Revolutions about the place of religion in society - played an important role in developing the idea of civil religion. This challenges the conventional understanding of civil religion as an Enlightenment concept. It also contests the view that it was a cynical ploy to undermine religion. Instead, it is demonstrated that, for many who advocated these ideas, the issue was priestcraft not religion itself; and the aim was to purify the church rather than to undermine religion.

Taking this last point first, Mark Goldie's opening chapter in the book presents the idea of a 'Christian civil religion' which was indebted to the magisterial reformation of the sixteenth century but also to late medieval Catholic conciliarism. These debts have been neglected because of the tendency to see Christianity as constructed in opposition to civil religion, but Goldie's account shows what can be gained from looking at the early modern period from this perspective. That picture is deepened and complicated in other chapters, not least those by Charlotte McCallum and Jacqueline Rose. McCallum's chapter focuses on 'Nicholas Machiavel's Letter to Zanobius Buondelmontius in Vindication of Himself and His Writings', which appeared in John Starkey's 1675 edition of Machiavelli's works, but was probably written by Henry Neville. It presents a powerful example of a form of civil religion that was anti-clerical but was aimed at the eradication of priestcraft not religion itself. This was Neville's own position, but the letter also raises interesting questions about Machiavelli's views and his place within the conventional narrative of civil religion. Rose's chapter complicates the story presented here. She notes that Anglo-Saxon history offered an obvious model of a church free from Popish and priestly corruptions. Yet, as she explains, it was never taken up as a model of civil religion by early modern thinkers. Despite the similarities between Reformation languages of godly rule and Royal Supremacy and the ideas associated with civil religion, there were also important differences that restricted its value as an appropriate model.

Other chapters explore the debates concerning the relationship between religion and politics, church and state, that occurred between the 1590s and the late seventeenth century. Polly Ha's chapter focuses on the debates sparked by the Admonition controversy in the 1590s and the ways in which this led to a reconfiguring of the relationship between church and state, with figures like Richard Hooker advocating an extension of the state's right to determine the religion of its subjects. Esther Counsell examines the reaction to the rise of Laudianism within the Anglican Church in the 1620s and 1630s, showing how Alexander Leighton saw the revival of an ancient form of civil religion as the best means of protecting the Reformed church by securing the civil supremacy of parliament over the church. The chapters by John Coffey and Connor Robinson consider the contested period of the 1650s, when the rise of Independents challenged any notion of public or formal religion, further reshaping the relationship between church and state. Where Coffey focuses on republicans and independents, Robinson considers the debate between Henry Stubbe and Richard Baxter over the nature of a godly commonwealth, challenging the conventional interpretation of Stubbe that presents him as an advocate of a novel form of Enlightenment civil religion. Finally, Andrew Murphy and Christy Maloyed's chapter, along with that by John Marshall, take the story on to the later seventeenth century, and beyond England to the American colonies. Murphy and Maloyed argue that William Penn attempted to enact a form of civil religion - combining civil interests with general religious beliefs - in Pennsylvania. Marshall presents John Locke as working out the appropriate relationship between church and state and highlights the complications brought to these debates when thinking about the colonial context and how toleration and liberty were conceived there.

Overall, then, the volume reflects on the complexity of early modern debates over the relationship between church and state. It also demonstrates the flexibility of the ideas involved, with arguments for state control over religion being deployed by individuals and groups with a range of different views and sometimes even on both sides of an argument.

For Hobbes, civil religion offered a means of securing peace and stability in a world in which individuals hold divergent opinions, preferences and beliefs. We may baulk at his authoritarian solution, but the problem of how to live peacefully despite our differences continues to confound us today.