This year the town in which I live is celebrating 800 years since its foundation. In 1225 a fishing port, accompanied by a small village of huts known as ‘shiels’, was established on the north bank of the Tyne to serve Tynemouth Priory which was situated on the headland at the mouth of the river. The port grew into a harbour and the town expanded so that today around 35,000 people live in North Shields and the surrounding area.

The mouth of the Tyne during the blessing of the fleet ceremony to celebrate North Shields 800 on 20th June 2025. Image by Joan Hammersley, 2025.

As a historian I have been interested in the history of the area since moving here over twenty years ago. From the perspective of the UK as a whole, North Shields might seem like a remote backwater, but for various reasons it played a crucial role at several points during the historical period I am most interested in (1500-1800), not least during the mid-seventeenth-century revolution.

As its origins would suggest, the importance of this area has always been linked to its position at the mouth of the river Tyne, approximately seven miles east of Newcastle. Fishing boats have gone out from North Shields continuously since its foundation. A few still do so today, and Fish Quay remains a great place to buy fresh fish. In the early modern period, though, the Tyne was also important for another reason. It was crucial in the transportation of coal from the rich northern coalfields to other parts of the country - most notably London. Throughout that period coal was the key source of fuel that was essential both for heating and cooking. Consequently, the position of North Shields at the mouth of the Tyne gave it importance within the country and accorded those who controlled it particular power.

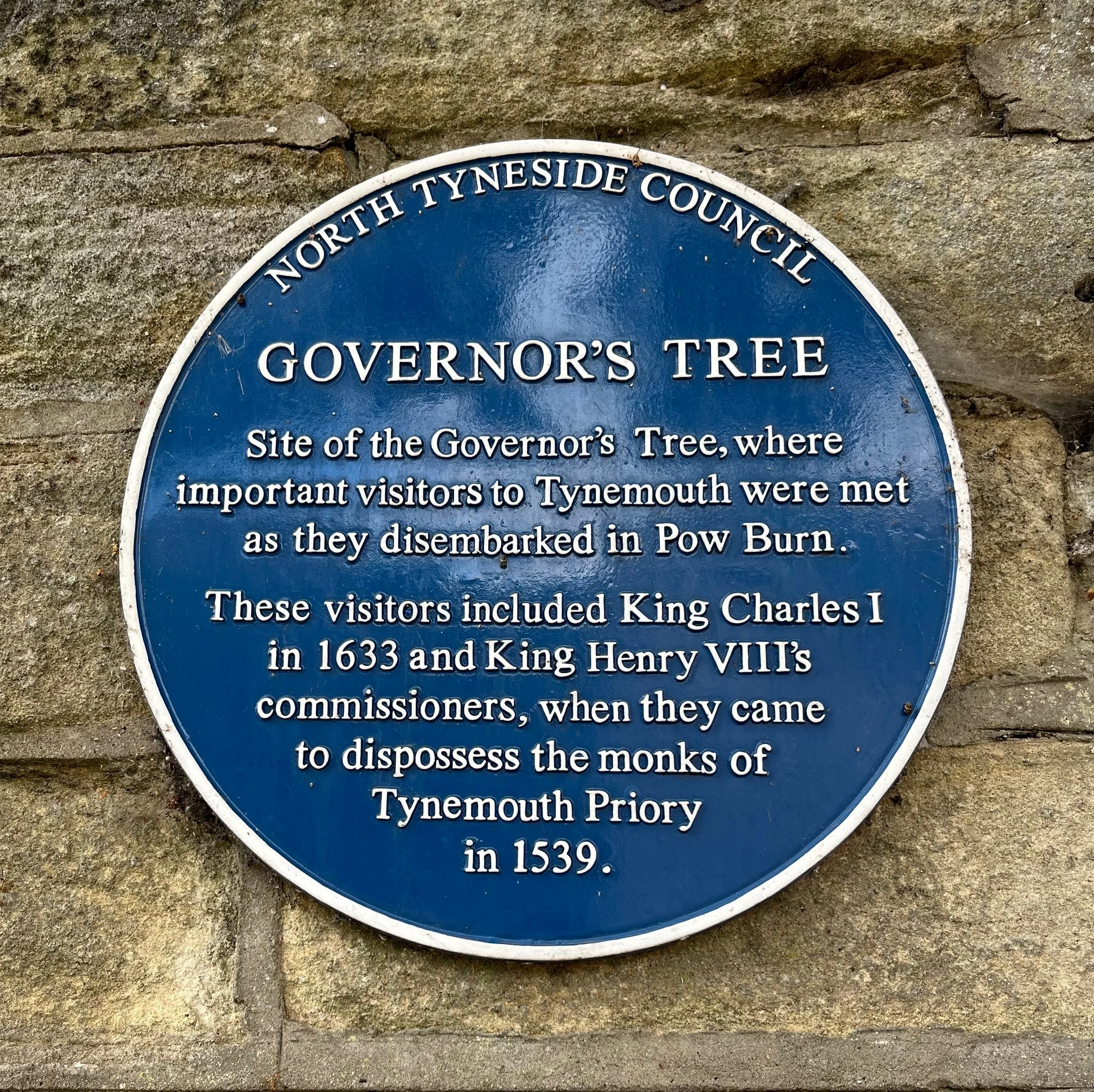

The plaque marking the site of the so-called ‘Governor’s Tree’ in North Shields. Image by Rachel Hammersley, 2025.

It was perhaps because of its importance in the coal trade that Charles I visited North Shields in June 1633. He had become King of Scotland and England in 1625 following the death of his father James I. He was crowned in England on 2 February 1626, but did not travel north for his Scottish coronation until the late spring of 1633. He left Whitehall on 8th May, but made slow progress, not reaching Durham until June. He made a state entrance into Newcastle on 3rd June, before travelling by barge down the river Tyne to see the ships at anchor on 5th. According to a plaque situated on Tynemouth Road close to the border between Tynemouth village and North Shields, he was welcomed there at the Governor's Tree having disembarked in the Pow Burn, though the veracity of the plaque has been questioned. Unfortunately Charles's visit in June 1633 was not without incident. One of the naval guns that was fired in his honour exploded, killing three men and injuring several more.

An image depicting the opposition to the Book of Common Prayer in Scotland. Taken from True Information of the beginning and cause of all our troubles (London, 1648). From the copy in the Philip Robinson Library, Newcastle University: Special Collections Bradshaw 942.062 TRU. Reproduced with kind permission.

Charles was back in Newcastle again between 5 and 22nd May 1639 - though he probably did not visit North Shields on that occasion. This visit was prompted not by ceremony but politics and reflected a third reason why this region was important in the seventeenth century (besides fishing and the coal trade): its proximity to Scotland. Keen to harmonise the religious establishment and practices of his two kingdoms, Charles had sought to impose the English Book of Common Prayer and rule by Bishops on the largely Presbyterian Scots, prompting riots in churches and war between England and Scotland. Charles struggled to raise English troops to fight in Scotland and on his visit in May 1639 he found the troops in a poor state. Just over a year later the King's English forces were defeated by the Scots at the Battle of Newburn to the west of Newcastle. The Scots then entered and occupied Newcastle on 29 August 1640 and the coal trade to London was suspended. The Treaty of Ripon of 14 October dictated that the Scots would occupy the North East (and be paid quartering costs while doing so) and that Parliament would have to be party to a final settlement. This forced the King's hand and was instrumental in bringing about the Civil War. Charles had ruled without Parliament between 1629 and 1640 and the 'Short Parliament' called in the spring was quickly dismissed. This move on the part of the Scots forced Charles to call Parliament again in the autumn of 1640, thereby opening a channel through which his English subjects could voice their own grievances

The mouth of the Tyne remained important throughout the Civil War. For the reasons discussed above, Charles was keen to secure the northern counties for himself and he sent the Earl of Newcastle to the region in June 1642. Three hundred soldiers were dispatched to Tynemouth Castle to guard it, the Earl constructed forts at Shields, and men were recruited for defence. Control over the river was also strictly enforced - one seafarer, a Captain Johnson, described trying and failing to get his boat into Tynemouth Haven for fresh water because there were 80 men fortifying the fort next to the old castle. (House of Lords Journal, 5, pp. 170-1, 1 July 1642 'Abstracts of Letters from Newcastle'). Control of the river continued to be a bargaining chip between the two sides. By January 1643 John Marley had been elected mayor of Newcastle and the town was firmly in royalist hands. In retaliation Parliament insisted that London coal ships were not allowed to sail to and from the town until Marley and the other local officers changed sides. While this was a tactical move by Parliament, it resulted in London, which was by then under Parliamentary control, suffering from a lack of coal.

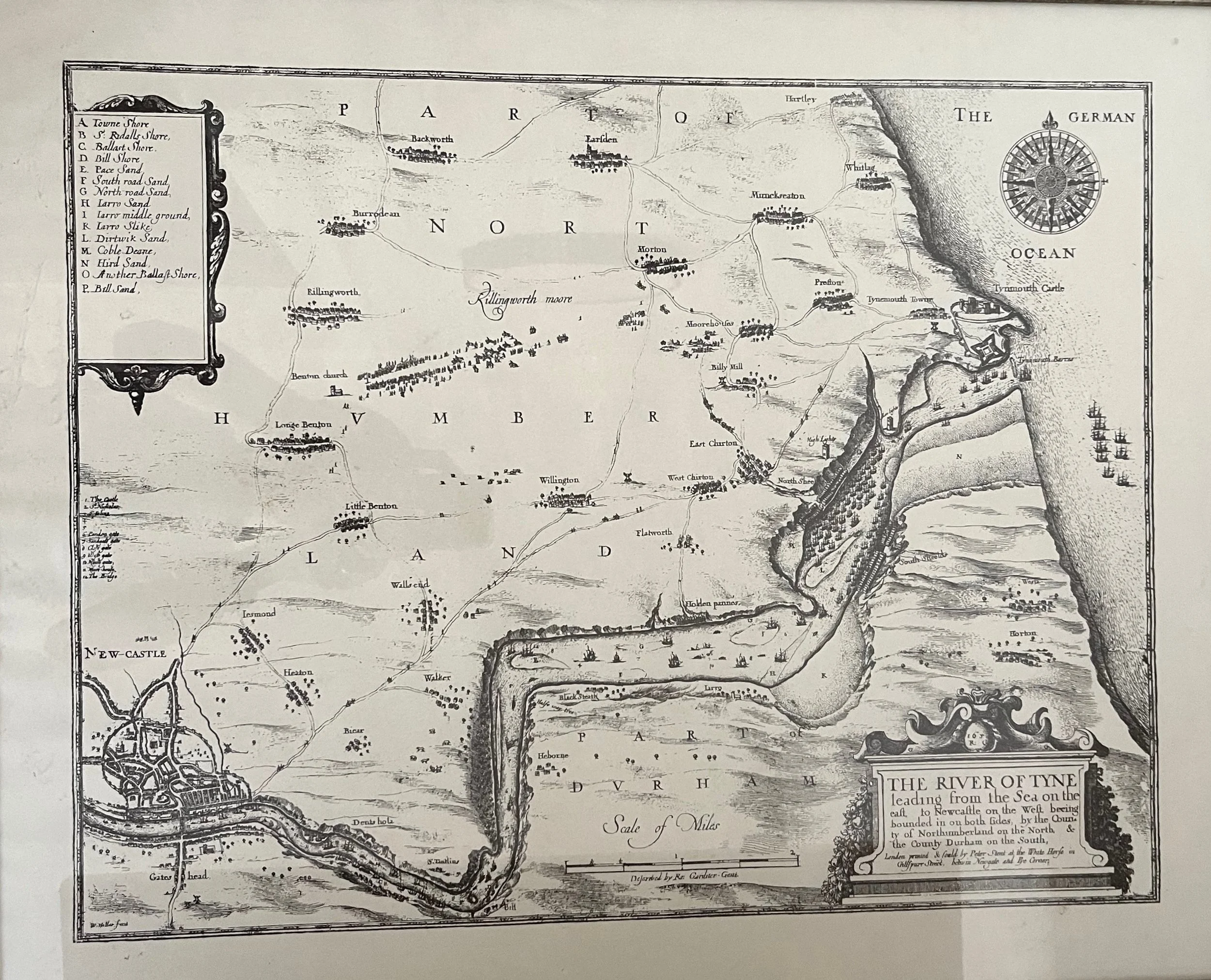

The author’s copy of a map of the Tyne from Ralph Gardner’s England’s Grievance Discovered (London, 1655).

It was this situation that led to the siege of Newcastle in 1644. Scottish troops under General Alexander Leslie (who had led the Scots to victory at the Battle of Newburn) besieged Newcastle from late August with the aim of re-capturing the town for Parliament in order to re-open the London coal trade. The siege ended with a two-hour bombardment on 19 October. Leslie subsequently besieged and captured Tynemouth Castle and by November both were firmly in Parliamentarian hands.

The memorial to Ralph Gardner in Chirton North Shields. Image by Rachel Hammersley, 2025.

As well as becoming pawns in the conflict between Royalists and Parliamentarians, coal and the river Tyne were also a source of local tensions. In 1655 Ralph Gardner, who was from Chirton close to North Shields, published a pamphlet entitled Englands grievance discovered in which he detailed the negative consequences of the control exercised by the Newcastle Mayor and Burgesses over the river Tyne from its mouth to beyond the Tyne bridge, and therefore of the coal trade from the North East. He claimed that both ship owners and local people from Shields had lost money and business as a result and that the heavy-handed imposition of control by the Mayor and Burgesses had resulted in ships sunk unnecessarily and individuals imprisoned and fined simply for doing their job. Gardner commissioned the artist Wenceslas Hollar to produce a map of the Tyne to accompany his work which demonstrated, in stark visual form, the distance from the mouth of the Tyne to Newcastle, and therefore the folly and injustice of the Newcastle corporation's insistence on controlling the trade.

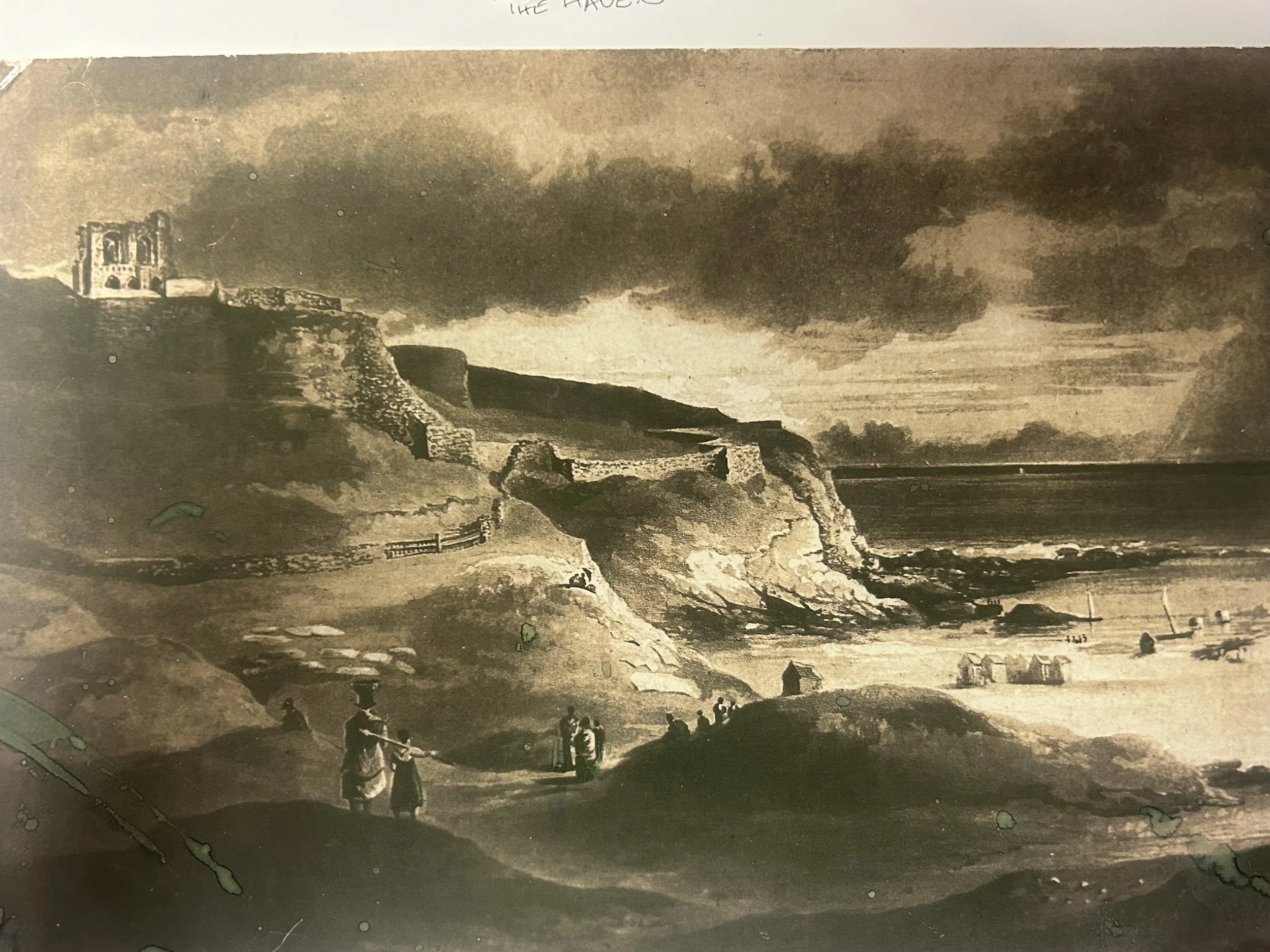

Tynemouth Priory from Priors’ Haven in around 1800. This shows where the Parliamentarian troops would have put up ladders to scale the headland. I am grateful to English Heritage staff at Tynemouth Priory for providing me with a copy of this image.

Finally, the importance of the area around the mouth of the Tyne helps to explain why the defection of the Governor of Tynemouth Castle, Colonel Henry Lilburne, in the midst of the renewal of fighting known as the Second Civil War, was viewed as a major emergency. Lilburne came from a staunch Parliamentarian family from County Durham. One brother, Robert, had been a long-standing Parliamentarian officer and the other, John, was a leading figure in the Leveller movement. Yet in August 1648 Henry suddenly declared himself for the King and sent to North Shields calling on 'all that loved him and King Charls to come to the Castle for his assistance' (Sir Arthur Hesilrige's Letter to the Honourable Committeee of Lords & Commons at Derby-House, Concerning the Revolt and Recovery of Tinmouth-Castle. London, 1648, p. 4). Arthur Haselrige, the head of Parliamentarian forces in the north, sent a considerable body of foot soldiers and dragoons down the river and ordered them to storm the castle at night, using ladders to scale the headland from the water. The task was hard:

but at last ours mounted the works, recovered the castle, and killed many Sea-men

and others, and amongst the number that was slain, they found Lieut: Col: Lilburn

(Sir Arthur Hesilrige's Letter, p. 6).

Tynemouth Priory on the 11th July 2025 as preparations were being made for the Mouth of the Tyne festival. Image by Rachel Hammersley, 2025.

The complex background to Lilburne's defection has recently been investigated by one of my students at Newcastle University, Lucy Delaney. It is a fascinating story revealing the complex interplay between local and national issues and events. That interplay has always been important in this north-east corner of England. Despite its distance from London, geographical, topographical and historical factors have rendered it relevant to the national narrative over centuries. The evidence of this remains in the landscape itself, particularly at the mouth of the Tyne. The headland proudly wears the remnants of its 800+ years of history - national, local and personal - in the priory and castle ruins (now an English Heritage site), gravestones, World War Two gun emplacements, and even the defunct coastguard station. These evidence the diverse roles it has played over the years. Moreover, as I write this, preparations are being made for the annual 'Mouth of the Tyne' music festival, which means that a huge stage has been erected between the Coastguard Station and the Priory ready to welcome the hundreds of revellers who will come to hear the bands that will be playing. This area may be rich in history, but it is also a vibrant place that remains of relevance and value today.