One of the frescoes from the Peers’ Corridor in the Palace of Westminster. Reproduced from Wikimedia Commons.

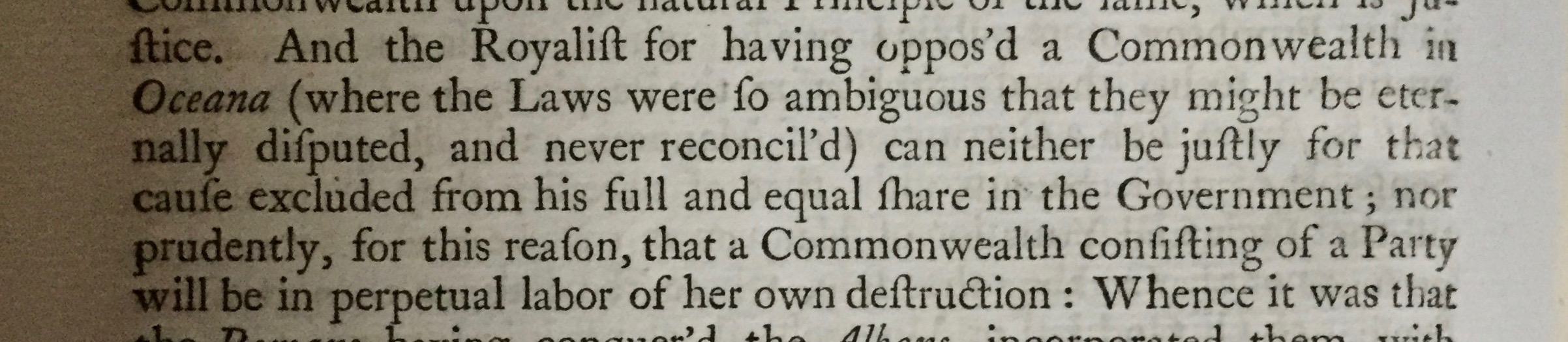

In the Peers' Corridor of the Houses of Parliament, which leads from the central gallery to the House of Lords, eight frescoes by the Victorian artist Charles West Cope are mounted on the walls. On one side of the corridor are four pictures that depict events from the mid-seventeenth-century Civil Wars from the Parliamentarian perspective, on the other are four paintings that offer a Royalist account. They were commissioned as part of the refurbishment of the Palace of Westminster following a devastating fire in 1834. The idea behind the paintings, and the way in which they are hung, was to represent the fact that the two sides had fought each other during those wars, but that they were now unified once again and working together for the good of the nation. This scheme, and the careful consideration that went into it, reflects the difficulties involved in commemorating the events of the mid-seventeenth century.

Reconciling ourselves to the history of the British Revolutions (1640-1660 and 1688-1689) is perhaps less of a problem today, since those events are no longer central to British public consciousness or the understanding of our own history. In part this reflects the fact that the mid-seventeenth century features only fleetingly in the school history curriculum. Yet the events of those years still resonate in the way in which we conduct parliamentary politics. The adversarial model of parliamentary debate, the fact that the monarch cannot enter the House of Commons without permission, and the exclusion of Roman Catholics from the line of succession to the throne, all date from the seventeenth-century conflicts.

On 3rd September we held a workshop at Newcastle University on 'Memory of the British Revolutions in the 17th, 18th, and 19th Centuries'. Organised in collaboration with colleagues at the Université de Rouen in France, this was a second workshop aimed at building towards a big grant application 'Memories of the English Revolutions: Sources, Transmissions, Uses (17th-19th centuries)' (MEMOREV). This workshop brought together a number of British and French scholars from different disciplines and career stages to consider how the 1640-1660 and 1688-1689 revolutions were remembered, forgotten, contested and reinvented across the British Isles, Europe, and North America between the mid-seventeenth and the early twentieth century. The aims of the wider project (as set out in the workshop by Claire Gheeraert-Graffeuille) involve several elements:

Linking the conflicts of the 1640s and 1650s with those of the late 1680s and early 1690s. These were often linked retrospectively and, as Jonathan Scott has shown, many of the issues that were fought over in the 1640s were unresolved in 1660 and surfaced again at the time of the Glorious Revolution

Taking a broad geographical approach encompassing not just the British Isles but also continental Europe and North America so as to re-examine the impact of these revolutions on European and transatlantic cultures

Exploring the tension between memory and history and the way in which the two impact each other, including the importance of remembering and forgetting in the fashioning of historiography.

In what remains of this blogpost I will explore my own reflections on this stimulating workshop.

While the British Revolutions may no longer hold the place in the public consciousness they once did, episodes from that era still create tensions or problems for those engaged in remembrance, memorialisation, and even historical interpretation. As an historian who regularly teaches the British Revolutions I am acutely aware of this. I know the horrifying fact that the proportion of the population that died in the civil wars was greater than in World War One, and despite my republican sympathies I am uncomfortable discussing - let alone celebrating - the details of the execution of the King.

As several speakers from our workshop highlighted, the violence and the regicide have created difficulties for those remembering the events ever since the seventeenth century. Isabelle Baudino's paper was particularly strong on this. While early visual narratives of the period, such as A True Information of the beginning and cause of all our troubles and John Lockman's New History of England, did present the violence - the latter including an image of the execution of Charles I by Bernard Picart - later versions replaced these images with tableaus that encapsulated the event without actually depicting the brutality. Isabelle focused on two scenes that proved particularly popular as means of presenting the regicide and Cromwell's reign respectively in ways that were not too shocking or distasteful.

‘Charles the First after parting with his children’ by Samuel Bellin, published by Mary Parkes, after John Bridges. 1841 (1838). National Portrait Gallery NPG D32079. Reproduced under a creative commons licence.

Rather than depicting the regicide itself, the authors of narrative histories began alluding to that event by recreating the king's final farewell to his children. As Isabelle noted, the regicide was effectively present in this scene, since the reason Charles was having to take leave of his family was because he had been condemned to death, but the act itself was not shown. That farewell scene became ubiquitous not just in narrative histories but also in other forms, right up to Ken Hughes's 1970 film Cromwell.

The other scene Isabelle discussed also features in that film. It was Oliver Cromwell dissolving the Rump Parliament in April 1653, which became a symbol or shorthand for Cromwell's authoritarian rule. As Myriam-Isabelle Ducrocq noted in her paper, Cromwell as a character has also been problematic for those remembering or offering an historical account of the British Revolutions. This is especially true with regard to his activities in Ireland, but Myriam-Isabelle showed that Cromwell was also a difficult figure for historians such as Frances Wright, whose grand narrative England, the Civilizer appeared in 1848. On the one hand Wright was critical of Cromwell's actions and yet she also sought to exonerate and redeem him, describing him as a wonderful man and a guardian of civilisation.

Plaque at Burford Church. Reproduced from Wikimedia Commons.

Wright saw the Revolution of 1640-1660 as a positive event, advancing the civilising process, yet for her - and for later parliamentarian sympathisers - it could be difficult to identify moments or characters worthy of celebration. Waseem Ahmed's paper addressed this issue from the perspective of the Left in examining 'Levellers Day', a commemoration of the Leveller mutiny which resulted in the execution of three men - Cornet Thompson, Corporal Perkins, and Private Church - at Burford in Oxfordshire in May 1649. Despite the violence of this event, and the fact that it marked the end of the main active phase of the Leveller movement, it is the date that Left-wing activists have chosen as a focus for celebration since the 1970s. In his talk, Waseem provided detail on the background to the annual Levellers Day celebration and drew out some of the complexities and tensions inherent in it. Though effectively a celebration of a moment of defeat it celebrates the bravery of these men who sacrificed their lives for a cause they believed in. Moreover, the event is important in offering an alternative history of the British Revolutions distinct from that offered by the establishment, and is part of a wider argument (encouraged by the Communist Party Historians’ group in the 1950s and 1960s) that England does have a revolutionary tradition.

A second theme that cropped up in several of the papers was the importance of networks - both familial and political - to the preservation of memories (especially more hidden or controversial memories). Cheryl Kerry's paper highlighted this in relation to the 'regicides' who had signed the death warrant for Charles I. She showed both that there was a great deal of intermarrying among regicide families and that a number of descendants of the regicides were involved or implicated in later plots and were prominent among the supporters of William III in 1688-89.

Interestingly, Stéphane Jettot demonstrated that the situation was very similar for a group on the other side of the political divide - the descendants of Jacobites. Again there is evidence of intermarriage and Stéphane particularly highlighted the role played by female family members in maintaining memories through the preservation of documents and artefacts.

Lucy Hutchinson by Samuel Freeman, C. 1825-1850. National Portrait Gallery NPG D19953. Reproduced under a creative commons licence.

Returning to the civil wars, Lucy Hutchinson, who was the focus of David Norbrook's paper, played a crucial role in preserving the memory of her husband, the parliamentarian Colonel John Hutchinson. David demonstrated how important members of her family then were in controlling the publication of the manuscript of her Memoirs and the format in which it appeared.

Gaby Mahlberg also touched on the importance of networks, this time of those with similar political views, in her paper on the dissemination of texts and images relating to the regicide Algernon Sidney in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Germany. Gaby noted the important role played by Thomas Hollis and his circle in the creation and circulation of key images. Members of that circle included the Italian painter and engraver Giovanni Battista Cipriani, the German engraver Johann Lorenz Natter, and the Baron Stolzh.

Giovanni Battista Cipriani’s engraving of Algernon Sidney for the 1763 edition of Sidney’s works commissioned by Thomas Hollis. National Portrait Gallery NPG D28941. Reproduced under a creative commons licence.

Hollis and his circle worked hard to keep the memory of the British Revolutions alive in Britain and abroad in the late eighteenth century and saw connections between the events of the mid-seventeenth century and their own times. The third theme that stood out to me from the workshop papers was the importance of reverberations and feedback loops both in preserving memories (by ensuring that events remained relevant) but also in distorting the way in which particular events were remembered.

Several participants highlighted the fact that in nineteenth-century France, discussing the English Revolutions was a subtle way of commenting on the French Revolution and contemporary events in France. In his paper on nineteenth-century French school textbooks, Pascal Dupuy explained that parallels between the Stuarts and the Bourbons were especially common in the Restoration period and that discussions of the Stuarts could be read as comments on the contemporary French monarchy.

Another obvious parallel for the French was that between Napoleon Bonaparte and Oliver Cromwell. As Isabelle Baudino explained, Bonaparte's coup added a new urgency and relevance to the image of Cromwell dissolving the Rump Parliament. It was not only for the French that Cromwell was a striking character. As Maxim Boyko demonstrated in his paper, Cromwell was interpreted by some Italians through a Machiavellian lens. Maxim noted that the Italians also tended to understand the period of the commonwealth and free state between 1649 and 1653 through the lens of the Italian city states, not least Venice.

These ideas have been very much in my mind as I returned to teaching. In my first week back I encouraged undergraduate students on my special subject 'The British Revolutions, 1640-1660' to think about some of the resonances of that period today. I also engaged in a lively discussion with MA students on British values and citizenship and the extent to which these are rooted in history. I hope the MEMOREV project will offer further opportunities to explore the symbiotic relationship between the past and the present, memory and history.