The image of a Spence token sent to me by Malcolm Chase. Image Rachel Hammersley.

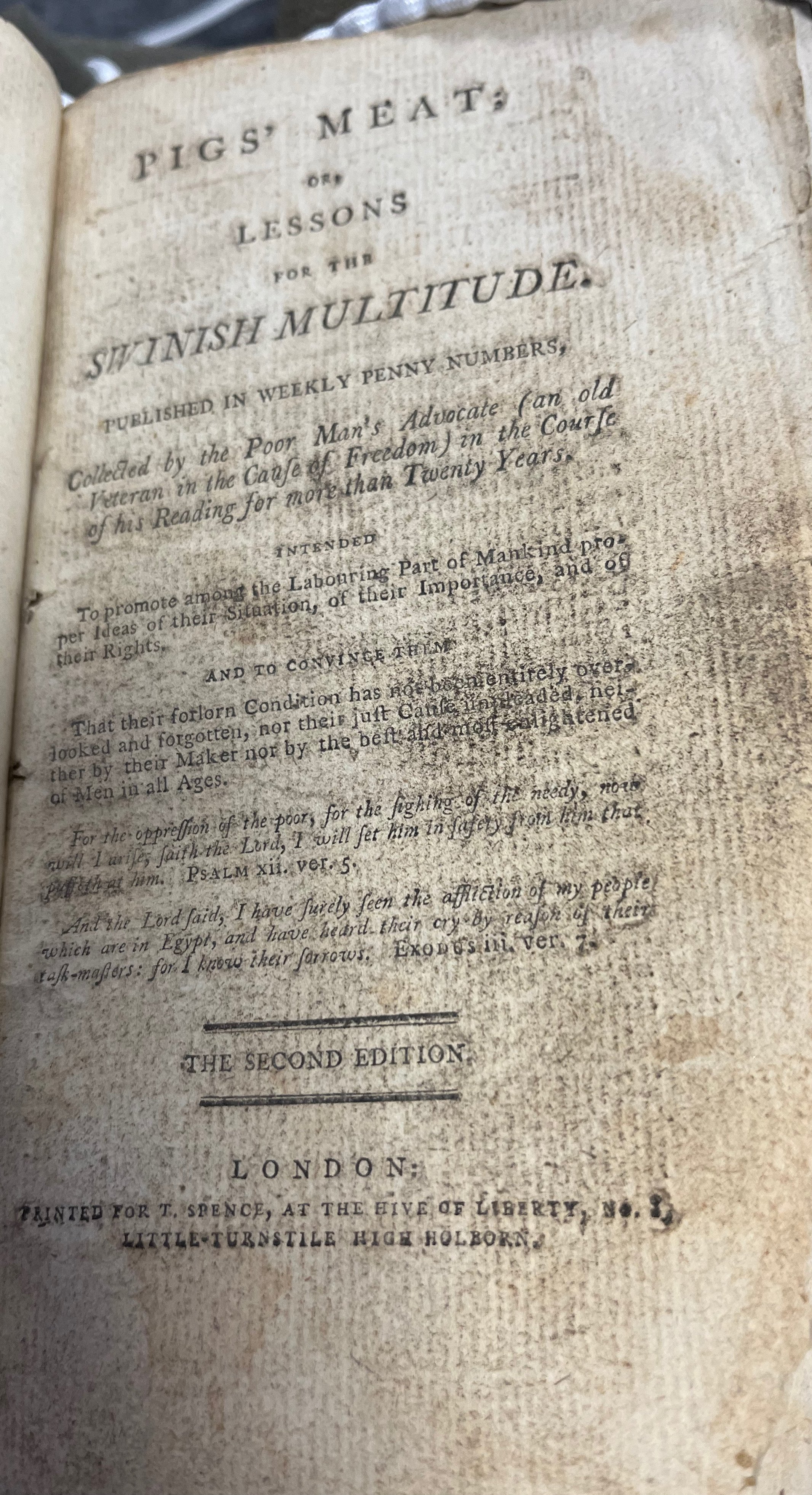

I start with a marvellous coincidence. At the end of November, I spoke at the symposium 'The Radical North, 1779-1914' which was organised at the University of Leeds, under the auspices of Northern History and with support from the Social History Society, to celebrate the life and work of Professor Malcolm Chase (1957-2020). As I began preparing my talk on Thomas Spence and the political culture of late eighteenth-century Newcastle, I spotted the photograph of a Spence token on the shelf beside my desk and thought I could use it as one of the illustrations. As I removed it from its frame I noticed that there was a message on the back and I realised that the photograph had been sent to me and my then husband, John Gurney, by Malcolm himself in 2007 as a 'New Year's Gift'. Though I have often looked at that photograph while working, I had completely forgotten that it was Malcolm who sent it to us. It seemed highly appropriate that I should have remembered as I began writing the paper, and I felt both Malcolm and John would have approved of my decision to dig more deeply into the life and times of Thomas Spence.

The symposium was a fitting tribute to Malcolm. It included excellent papers on topics ranging from Christopher Wyvill's Yorkshire Association to the legacies of Chartism in Lancashire, and the radical verse of the Pitman Poets. As always, what follows are my own reflections on the papers and the discussions they sparked.

Callum Manchester offered a thoughtful paper on the Yorkshire Association, which reminded us all of the problems associated with using the term 'radicalism', especially for the period before it was coined in 1819. As Callum explained, Christopher Wyvill is especially problematic in this regard because, while he fits neatly with some elements of the definition of a radical - in his sympathy for Dissenters; his staunch opposition to placemen and pensioners in the House of Commons; and his call for parliamentary reform - in other respects he does not. Callum's solution to this problem was to suggest that radicalism is not just about aims but also the methods deployed to achieve them. He argued that Wyvill's methods were moderate rather than radical, and presented him as taking a middle way between Edmund Burke and Thomas Paine.

Christopher Wyvill by Henry Meyer, after John Hoppner, 1809. National Portrait Gallery NPG D4946. reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

Callum's paper set a helpful framework for what followed, not least in encouraging us all to pay attention to labels and their applicability to particular individuals and groups. One particularly curious label that featured in several papers was 'Tory Radical'. It has been used to refer to 'the Factory King' Richard Oastler, who was the subject of Vic Clarke's paper. Oastler was a staunch campaigner against cheap factory labour and exploitation, and yet he worked closely with the Tory MP Michael Sadler in the General Election campaign of 1837, and even stood as a Tory candidate for Huddersfield himself. As Vic explained, Oastler's apparent political ambiguity was mirrored - and perhaps prompted - by his social ambiguity. His background as a steward at Thornhill made it possible for him to engage with both mill owners and factory workers, and to build networks across class and political lines. Later in the proceedings, Christopher Day noted that the label 'Tory Radical' has also been applied to James Heaton of Clitheroe, who deployed Chartist methods - including mass petitioning, fly posting, and organising public meetings - in resisting the Public Health Act of 1848.

In his paper, Andrew Walker spoke in more general terms about the celebration of 'Old Chartists' in the northern press in the last forty years of the nineteenth century, noting that some of these men had become more conservative over the years leading to them being described by some as 'Tory Chartists'. Finally, something similar is perhaps evident in the life of the pitman poet Lewis Proudlock, who was the focus of Jordan Clark's paper. Though a promoter of the rights of working people, Proudlock took great inspiration from Jacobite myths, not least the story of Amelia Radcliffe. The political status of Jacobitism in different contexts has been of interest to me ever since I came across Jean-Jacques Rutledge (a Franco-Irish Jacobite) who featured prominently in my first book. It was, therefore, interesting to see how this ambiguity played out in a Northumbrian context.

In the discussion, we agreed that rather than dismissing the notion of Tory Radicals as an oxymoron, we ought to take such labels seriously. The figures of the past do not always neatly fit the pigeon-holes into which later scholars want to put them. Paying attention to how they viewed themselves - in all its complexity and ambiguity - may reveal important things about their aims and methods.

Some of these so-called Tory Radicals also share something else in common, in being what we might think of as footnotes to history. Malcolm himself had a fascination for those obscured in the conventional historical narrative, and it was therefore appropriate that several such figures featured in the papers presented at the symposium.

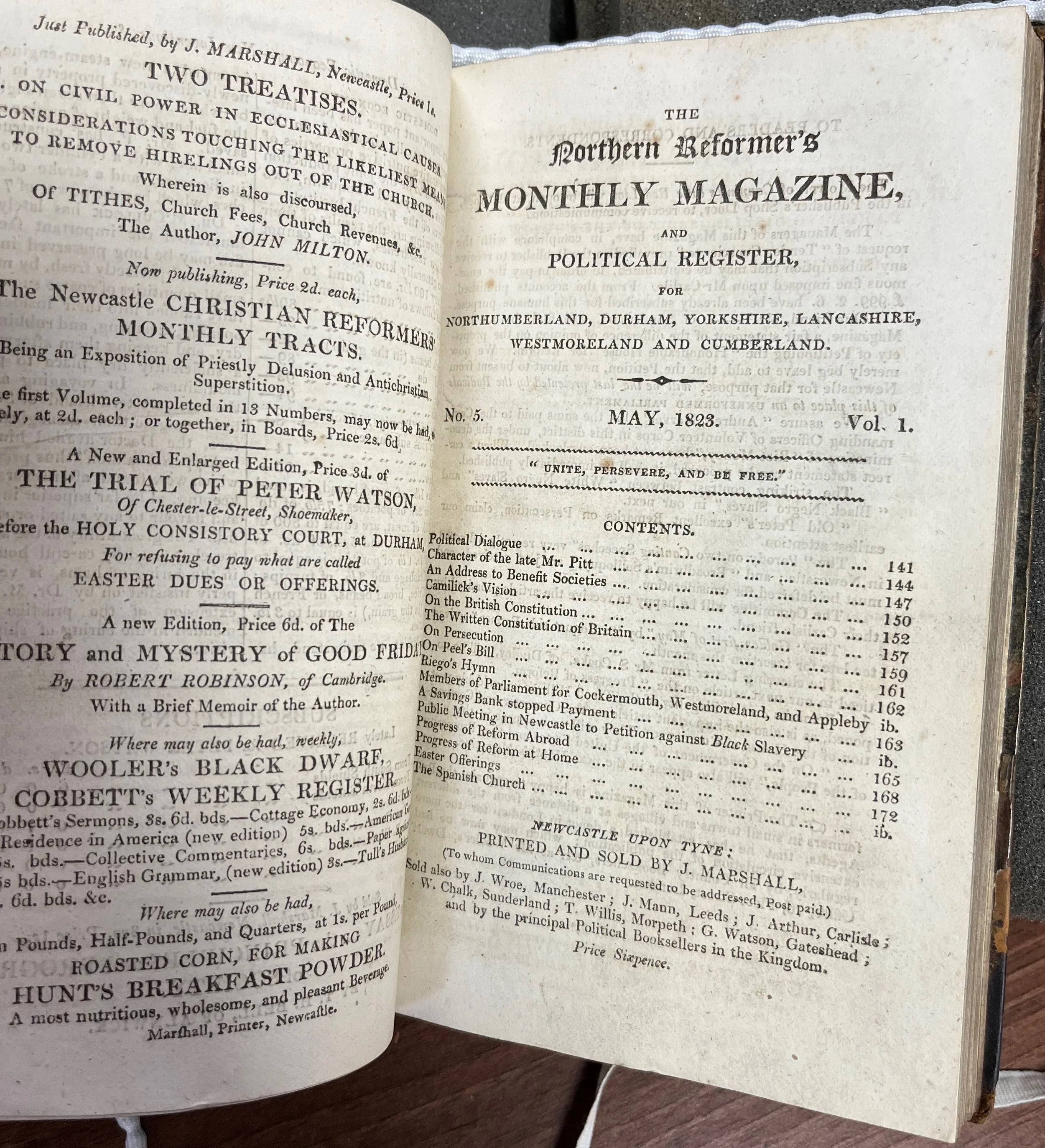

A copy of John Marshall’s The Northern Reformer’s Monthly Magazine from 1823. Philip Robinson Library, Newcastle University, Special Collections, Rare Books (RB 941.074 NOR). Reproduced with permission.

John Marshall, who was the focus of Harriet Gray's paper, is a good example of a forgotten radical. Marshall was a printer, bookseller, and librarian who lived and worked in Gateshead and Newcastle around the turn of the nineteenth century. He had links to better known radical figures including Eneas Mackenzie and William Hone, but Marshall himself is not well known and information on him is sparse. Nonetheless, Harriet did an excellent job of piecing together the evidence that does exist. Her paper, which was paired with my own on Thomas Spence, illuminated the political culture of the north east in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and demonstrated the various ways in which Marshall continued to disseminate Spencean ideas - via Spencean methods - long after Spence's own departure to London in the late 1780s.

Though living and working half a century later, and being based in Sunderland rather than Newcastle/Gateshead, Thomas Dixon - who was the focus of Joy Brindle's paper - reminded me a little of Marshall. He too was a disseminator and seller of books, but he also emphasised the importance of moving from thought to action. A distinctive element of Dixon's activity, which Joy explored in detail, was his letter-writing. He built up a large network of correspondents, which included several well-known figures. In his letters, as in his dissemination of books, Dixon's aim was to bring about tangible improvements to the working lives of those living in his locality.

The aim of improving the lives of working people also lay behind the petitions sent to Parliament from the north of England in the late nineteenth century, which were the subject of Henry Miller's paper. Most of the signatories to these petitions are complete 'unknowns', and yet in the words of the petitions we can hear the voices of ordinary people, thereby learning of their grievances and political concerns. Much the same is true of Martin Wright's account of the Northumberland miner's strike of 1887 and its impact on the wider socialist movement.

Richard Oastler, by James Posselwhite, after Benjamin Garside, 1841. National Portrait Gallery, NPG D7845. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

Another factor linking many of these obscure figures - and the papers at the symposium - is the important role played by religion in inspiring radical thought and action. Spence, Marshall, and Oastler were all driven by their faith, and referred to religious ideas and arguments directly in their writings. Other papers explored the influence of religious belief in more general terms. Andrew Walker paid attention to the impact of Methodism on the Chartists, while Tobin O'Connor offered a fascinating paper on the Labour Church in the 1890s. He argued that although it only lasted for a short time, and was quickly forgotten, it nonetheless provided an important path into the Labour movement for many working-class northerners.

Several of those who spoke specifically about Malcolm, referred to the importance to him of the connection between education and politics, and his commitment to sharing his knowledge with audiences beyond the academy. This was, of course, reflected in his first job at Leeds University in the Centre for Continuing Education, but he sustained his commitment to it long after transferring to the School of History. Katrina Navickas showed that, for Malcolm, politics and education were integral to each other, while Matthew Roberts and Robert Poole noted that he always wrote in a way that would engage the general reader and adapted his work to the interests and concerns of his audience.

Laura Foster also addressed the relationship between education and politics in her fascinating paper on reading and rambling groups such as the Eagle Street College in Bolton and the Clarion Sheffield Ramblers. Both clubs combined the reading and discussion of literature with walking in the countryside. Laura argued that in organisations such as these, participants created a space of pre-figurative politics in which the friendships and communities that were forged operated as a kind of microcosm of an ideal state.

This sense of creating an ideal politics through 'doing' is something that Malcolm Chase achieved in his own life and work - as was evidenced in the heartfelt testimonies offered by many of the participants. He was, his former colleague Laura King told us, a 'different kind of professor'. Though a talented and productive historian, he did not conform to the conventional academic and institutional hierarchies. He was consistently supportive of students and early career researchers. Pretty much everyone in the room appeared to have had the experience of a conversation with Malcolm about a current research project being followed up with a package of relevant material. In my case, I had simply presented a paper on Jean-Paul Marat's time in England to the History seminar at Leeds, which Malcolm had attended. A week or so later I received in the post a collection of ballads and offprints relating to Marat in Newcastle. I was neither a student nor a colleague of Malcolm's, and yet he treated my research with the same interest and generosity as those with whom he had closer connections.

Nor was it just those within the Academy who reaped the benefits of Malcolm's immense learning and kindness. He regularly spoke to non-academic audiences, ranging from parliamentary MPs to local history associations and adult education classes. Moreover, he genuinely acknowledged and valued the knowledge and expertise of those audiences. Malcolm's commitment to making historical and political knowledge widely accessible echoes the behaviour of many of the figures discussed at the symposium. Spence deliberately employed innovative methods - such as tokens, songs, and graffiti - to spread his ideas widely. Similarly, Marshall used his circulating library to make books available to the people of Gateshead, and Dixon often wrote letters to acquire key books for the people of Sunderland. Malcolm, then, embodied the marriage of scholarship and public engagement - of thought and action - that the figures he wrote about, from Spence to the Chartists, would have recognised and applauded.