Several recent commentators on world affairs, including Pope Francis and the Dalai Lama, have suggested that what is required to solve current problems is nothing short of a revolution. Despite my sympathy with the need for drastic change, as an historian of the English and French Revolutions I always feel cautious about calls for revolution. Both of the revolutions I have researched provide ample evidence of the horrors that it can bring: the havoc and destruction it wreaks on the country and the devastation it causes to individual lives.

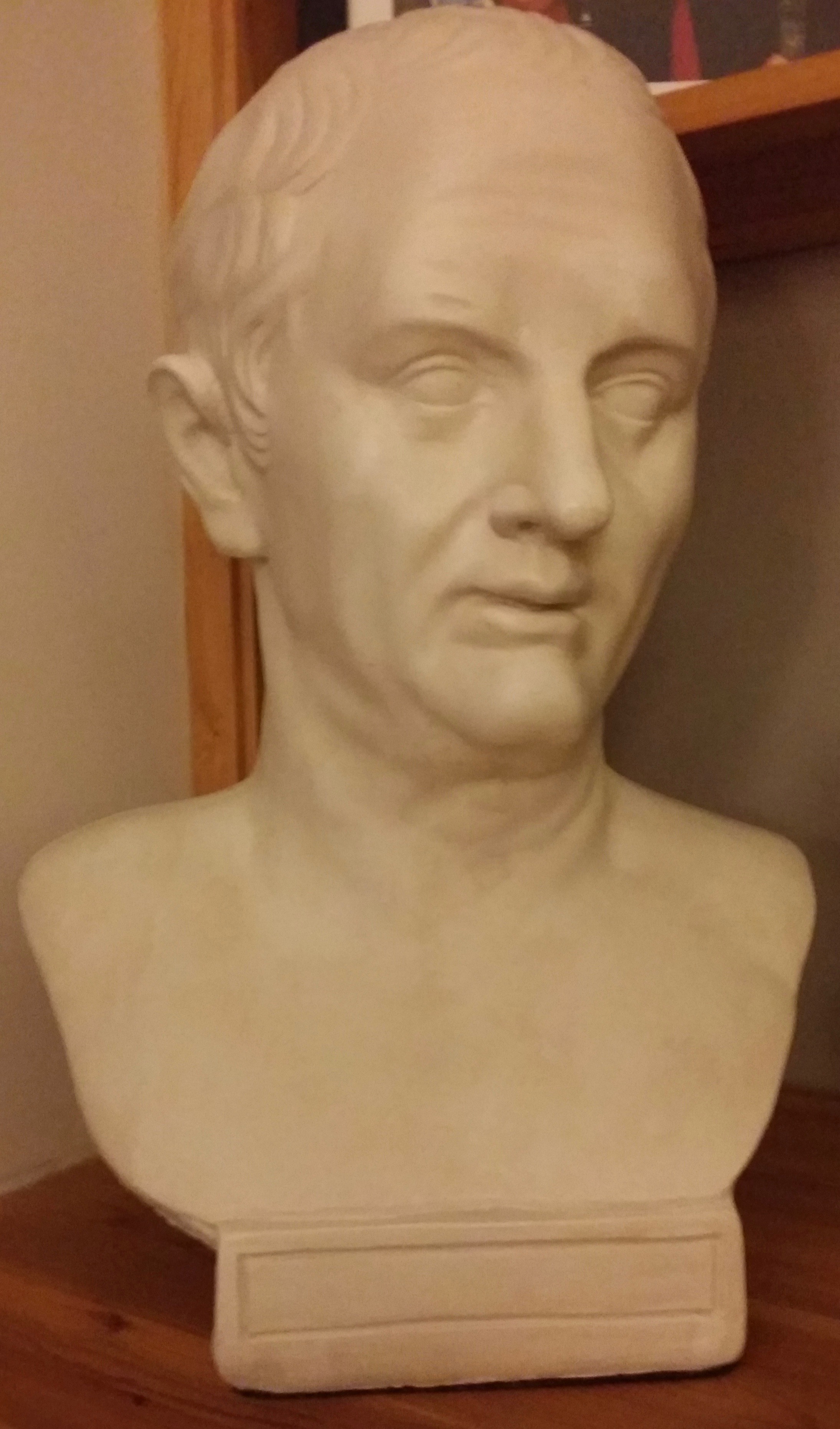

Statue of Oliver Cromwell at Westminster. Image by Rachel Hammersley

The Civil War, which was a key component of the English Revolution, is thought to have resulted, as noted in a previous blogpost, in the deaths of a larger proportion of the adult male population of this country than the First World War. The regicide - effectively a state-sponsored execution - that lay at the Revolution's heart, introduced a period of ten years of unstable government which had serious political and economic consequences. Moreover, the whole period brought division and animosity. Families were divided, with brothers or fathers and sons fighting on different sides. Royalists were excluded from the franchise in both of the constitutions of the 1650s: the Instrument of Government and the Humble Petition and Advice, as well as having their land and assets seized. After 1660 the tables were turned and it was former revolutionaries, especially the regicides, who were punished. Even his early death in 1658 did not protect Oliver Cromwell: his body was dug up in order to be posthumously decapitated. Moreover, the social divisions survived well beyond 1660, with the labels 'Roundhead' and 'Cavalier' mutating into those of 'Whig' and 'Tory', which dominated British politics throughout the eighteenth century and beyond.

'A Versaille, a Versaille, du 5 Octobre 1789'. Image from author's own collection.

The French Revolution has an even greater reputation for violence. This was frequently perpetrated by the crowds. For example, around the time of the storming of the Bastille, the decapitated heads of authority figures were hung from lampposts, and in October 1789 a crowd of women armed with pikes marched to Versailles and forced the royal family back to Paris. Later, in the September Massacres of 1792, over a thousand prisoners were slaughtered to prevent them from joining with foreign troops who were imminently expected to invade Paris (but actually never came). Violence was also perpetrated by the government itself, via the use of the guillotine and by the declaration, in September 1793, that Terror was the 'order of the day'.

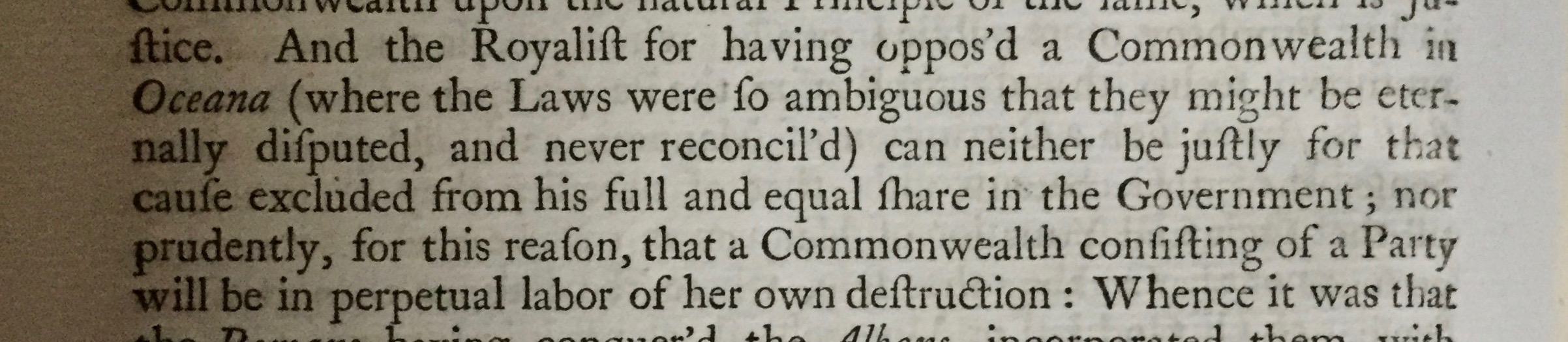

Of course, not all English or French revolutionaries insisted that violence and division were essential to achieving their aims. In each case there were prominent individuals who argued strongly against both. James Harrington was one of these. Though he supported the parliamentary cause financially during the 1640s, and argued that England was ripe for popular government in his major work The Commonwealth of Oceana of 1656, he acted as gentleman of the bedchamber to Charles I in 1647-8, having previously worked on behalf of Charles's nephew, the Prince Elector Palatine. In keeping with these connections, Harrington was intent, in the aftermath of the Civil War, on healing and settling a divided nation. To this end he even argued that royalists should be allowed to vote:

Extract from James Harrington, The Commonwealth of Oceana, in The Oceana and Other Works of James Harrington Esq., ed. John Toland, London, 1737, p. 74.

During the French Revolution calls for clemency were made by members of the Cordeliers Club who, as was demonstrated in my previous blogpost, showed an interest both in Harrington's works and in his understanding of democracy. In particular, Camille Desmoulins in his newspaper Le Vieux Cordelier, condemned Maximilian Robespierre's appeal to revolutionary necessity, which was used to justify the Terror. Against Robespierre's position, Desmoulins asserted the traditional Cordeliers call for the protection and defence of the rights of individuals, insisting that the Cordeliers' fight had been to defend: 'the declaration of rights, the gentleness of republican maxims, fraternity, holy equality, the inviolability of principles'. (Camille Desmoulins, Le Vieux Cordelier, Paris: Belin, 1987, p.80). Freedom of speech and the liberty of the press were particularly important to him as means of protecting the people against tyranny, and as the fundamental foundation of republican government: 'What is the last retrenchment against despotism? It is the liberty of the press ... What is it that distinguishes a republic from a Monarchy? It is a single thing, the liberty of speaking and of writing.' (Desmoulins, Le Vieux Cordelier, p. 147). Moreover, Desmoulins turned this idea directly against Robespierre's notion - borrowed from Montesquieu - of a republic of virtue:

But to return to the question of the liberty of the press, without doubt it must be unlimited; without doubt republics must have as their base and foundation the liberty of the press, not this other base that Montesquieu has given them. (Desmoulins, Le Vieux Cordelier, p. 179).

Camille Desmoulins, Le Vieux Cordelier, no. 4. Taken from Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France, http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/

Neither Harrington nor Desmoulins proved very successful in their attempts to bring about a more harmonious settlement. Despite his best efforts, Harrington's proposals were not taken up by the government. After the Restoration he was arrested and imprisoned by the authorities, and he did not publish any further works during his lifetime. Desmoulins suffered even more drastically for his views. He was sent to the guillotine in April 1794 by the man whose ideas he had criticised in Le Vieux Cordelier, his former schoolfriend, Robespierre.

Yet, just because they failed, does not mean that the ideas of Harrington and Desmoulins were not feasible, or that they do not have something useful to teach us. Most historians no longer subscribe to a narrow Whig interpretation of the past, but rather acknowledge that the ideas that did not win out, and even the paths not taken, are worthy of some consideration. Finding political solutions that can unite those of very different political persuasions (as Harrington sought to do) is an appealing idea at a time when politics is more divisive and combative than ever. And the notion that freedom of speech and a free press should form the foundation of the political system is widely respected, if not always enacted, today. Moreover, these two ideas are combined in an interesting initiative that has been gaining some traction. Advocates and practitioners of local participatory democracy have shown that allowing groups of interested parties openly to discuss and debate issues often leads to greater consensus. Applying this kind of local participatory democracy more widely could perhaps offer a solution to the current democratic crisis.

No doubt part of the appeal of Harrington's ideas to Desmoulins and his fellow Cordeliers was his attempt to combine a commitment to innovative and revolutionary ideas - not least democratic government - with a concern to heal divisions and to build a society that was open to a range of viewpoints as well as being harmonious. And I am aware that my own interest in both Harrington and Desmoulins stems partly from the same desire. For me, these thinkers offer the possibility that we may be able to bring about positive and lasting change to our society, including its political institutions, without recourse to revolutionary violence or even to the silencing of 'inconvenient' views.

![John Lilburne, England's New Chains Discovered, London, 1649. http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/leveller-tracts-6. 18.10.17. Taken from the Online Library of Liberty [http://oll.liberty.org] hosted by Liberty Fund, Inc.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57a64976d1758e28c2a46317/1508942506653-MC9ZTGQZPUPJNO70AQAP/Englandsnewchains.png)