Advances in digital technology have distanced twenty-first century scholars from the materiality of texts and the practical realities of printing and book production. I now access most of the texts I study via a screen. There are obvious benefits to this, virtually all the early modern printed texts I need are available via resources like EEBO (Early English Books Online) and ECCO (Eighteenth-Century Collections Online), so I no longer have to travel to specialist libraries to read them. Yet, being of an age that I can remember life before EEBO, I am also conscious of what is lost as a result of the shift to digital consumption. The orange dust on my clothes from carrying a pile of old books to my desk at the British Library is something I can live without, but the wealth of information that could be gleaned from handling the book as a physical object - its size, weight, quality, appearance - is much harder to intuit through a screen.

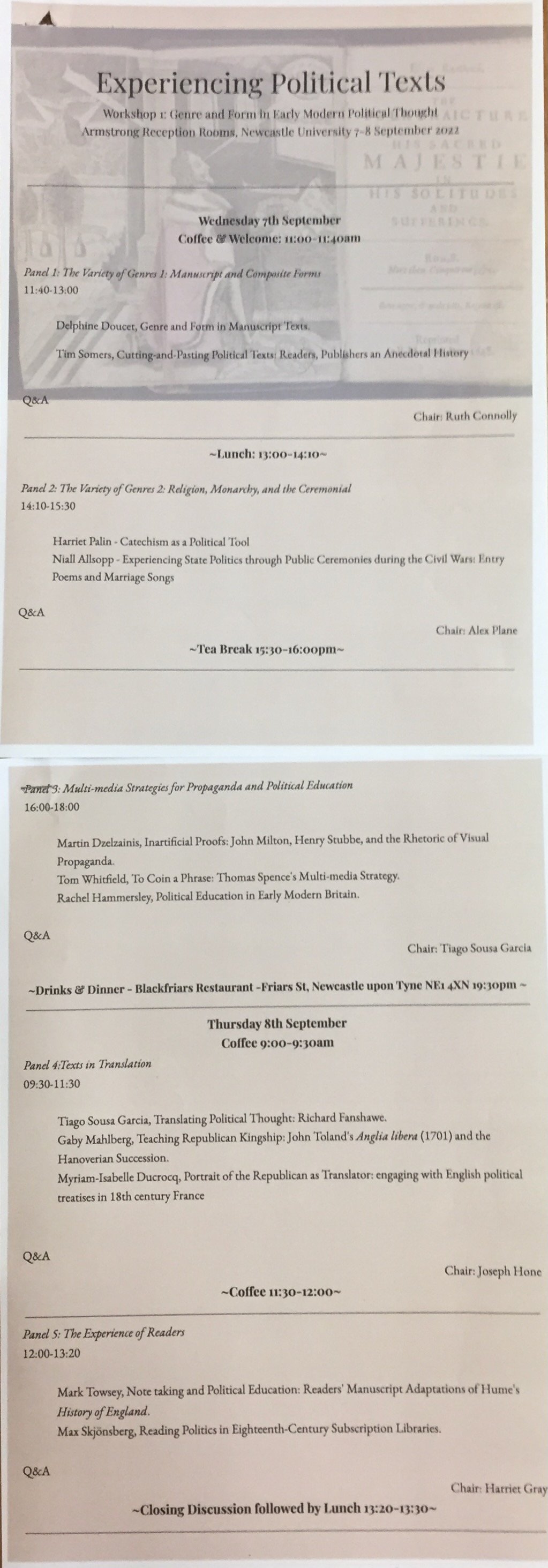

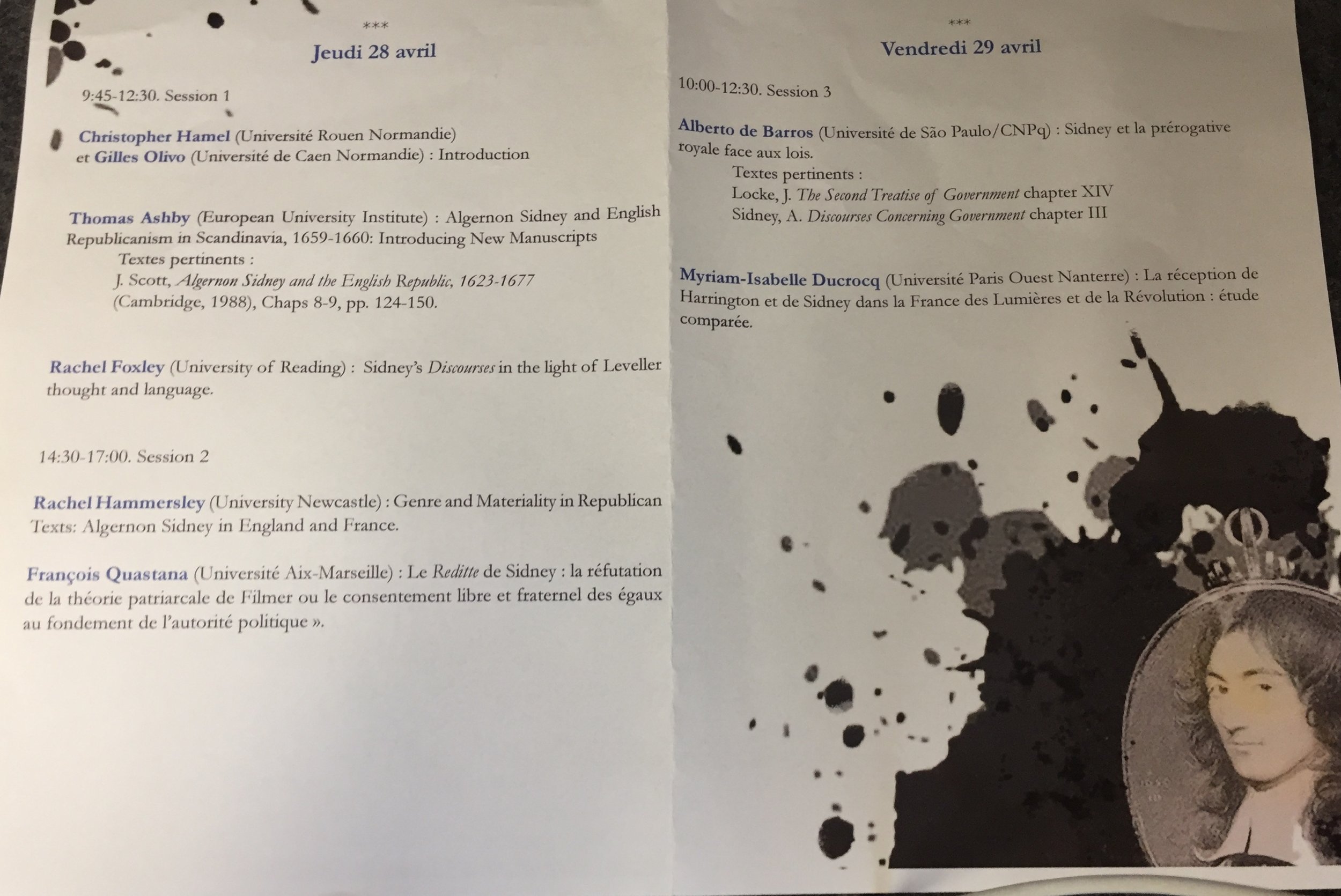

Our second Experiencing Political Texts workshop was designed to explore these issues by focusing on the materiality of early modern texts. Practicalities meant that we were also confronted with the pros and cons of the digital in our own experience of the workshop. Owing to the threatened UCU strikes, Part 1 took place in person in York on 24 February, while Part 2 (which I will discuss in my next blogpost) was broadcast via Zoom on 28 March. While there are definite advantages to being able to hold a workshop digitally, the engagement with participants - just like that with texts - is richer and more satisfying in person.

I left York buzzing with ideas, but will restrict myself here to just three: the experience of texts by non-readers; ephemerality versus durability and the role of text in securing longevity; and the notion of hidden texts - and more especially hidden political messages within texts.

The title page of John Lilburne’s pamphlet Regall Tyrannie Discovered (EEBO).

It was Sophie Smith who raised the point that texts are experienced by those who do not read them as well as by those who do. This idea was especially resonant because Sophie's paper followed Rachel Foxley's on Leveller and Republican texts, which had already led me to reflect on the information conveyed on title pages - which would have been accessible in booksellers shops or on barrows to people who did not buy or read the full work. Rachel focused on John Lilburne's Regall Tyrannie Discovered, the title page of which is particularly striking. It consists of dense, closely printed, type which sets out the argument and structure of the work. In this regard, it reminded me of the frontispieces to works like Thomas Hobbes's Leviathan and the Eikon Basilike, which convey the argument of the text in visual form. On the surface, these images are more engaging and might seem more appealing than dense type, and yet they require careful reading and interpretation. Lilburne also offered a textual equivalent of the author portrait that prefaced many early modern texts, listing his other works and offering a summary of the key events of his life.

An example of the Hugo Grotius medal from the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Taken from Wikimedia Commons.

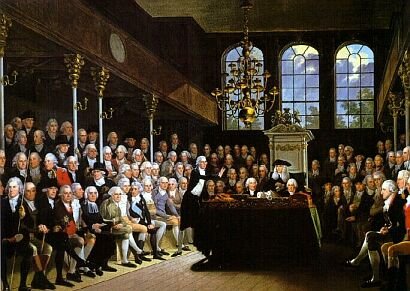

Of course, the reputation of an author - and an understanding of their main arguments - was often accessible to those who had never read that author's works. Niccolò Machiavelli was a case in point for the early modern period. Sophie showed that John Case's Sphaera civitatis was partly inspired by his concern that early modern citizens might derive their understanding of politics from Machiavelli (whether or not they had read him). By updating Aristotle's account of politics, Case's aim was to convince them to abandon Machiavelli as their guide. Charlotte McCallum's close reading of 'Nicholas Machiavel's Letter to Zanobius Bundelmontius' which appeared in the 1675 edition of his works, explored how Machiavelli could be drawn upon to advance arguments specific to English politics in the 1670s. Machiavelli was not the only figure whose reputation extended to audiences far beyond those who actually read his works. Ed Jones Corredera reminded us that the same is true of Hugo Grotius whose image was used to advertise air travel in the twentieth century and to celebrate individuals committed to advancing peace - via the Grotius medals, one of which was awarded to Winston Churchill in 1949.

Holy Trinity Church, York. As well as these surviving examples of early modern box pews, this church also has many tombstone inscriptions, not all of which are still visible. Image Rachel Hammersley.

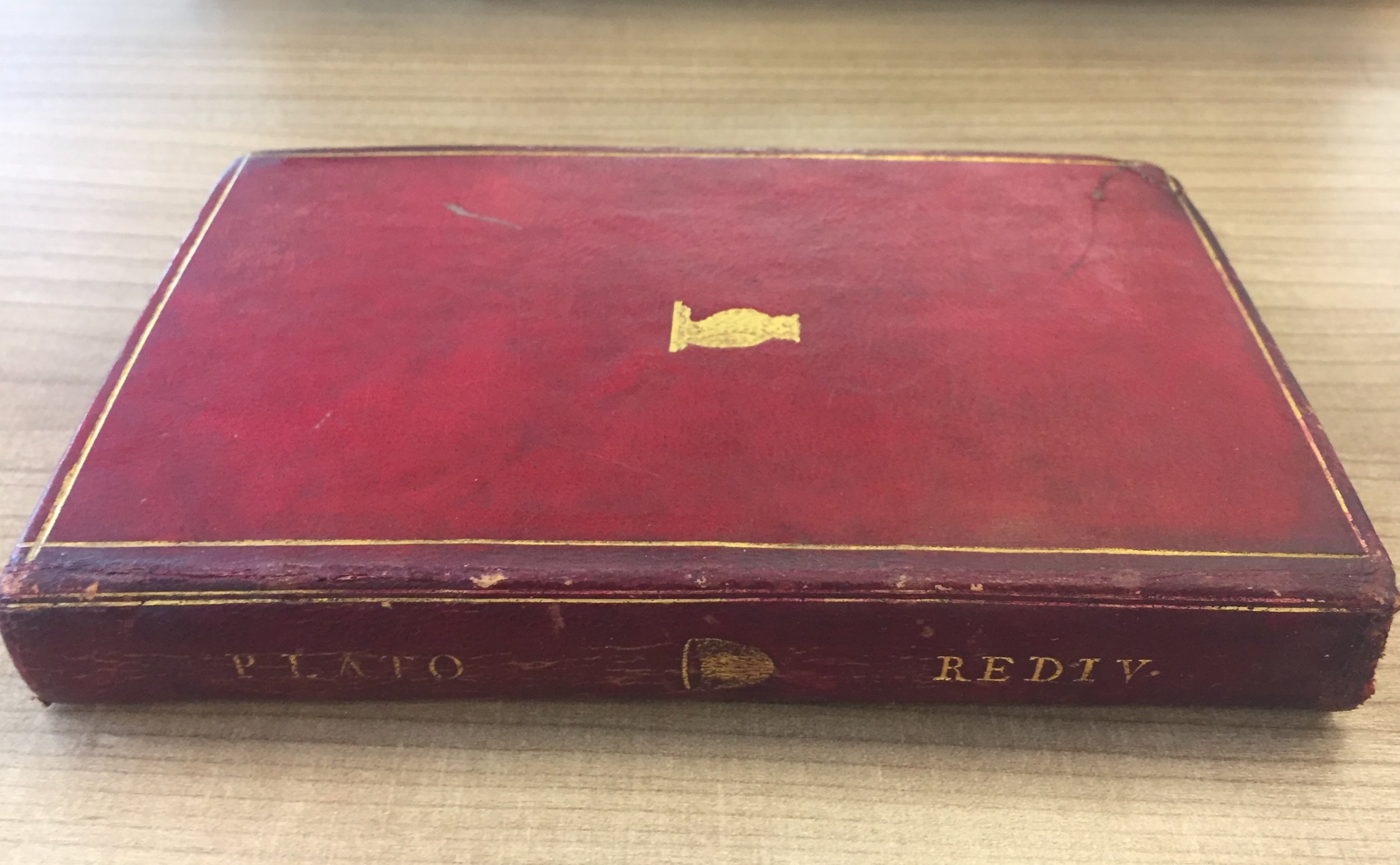

The second theme I drew from the papers concerned the ephemerality versus the longevity of texts. This idea was brought into focus by Katherine Hunt's paper which began with the line from George Herbert that writing in brass is more weighty, durable, and permanent than writing with pen and ink. As Katherine's paper demonstrated, the reality is that writing in brass could be just as ephemeral as print. As anyone who has wandered around a church will know, inscriptions on tomb stones can become worn over time. On the other hand, there are plenty of examples of supposedly ephemeral texts (broadsheets, chapbooks, pamphlets) that have survived since the early modern era. Sometimes this occurs as a result of them appearing in a Sammelband collection (a group of pamphlets bound together because they all relate to a particular issue or affair). Jason McElligott discussed a couple of Sammelband volumes held at the Marsh Library in Dublin. He demonstrated why such collections are so valuable to scholars, owing to their ability to reveal how particular works were read and understood at the time.

Rachel Foxley and Marcus Nevitt also touched on the contrast between ephemeral and more durable texts. In analysing Regall Tyrannie Discovered, Rachel was forced to confront the distinction between pamphlets and books. Lilburne usually produced pamphlets, but with Regall Tyrannie Discovered he was clearly aiming (not entirely successfully) to produce something more akin to a book. As Rachel noted, ephemerality versus longevity is one of several scales on which we can contrast these two formats. Though there are of course plenty of examples of pamphlets that have transcended their supposedly ephemeral status. Marcus noted the contrast between the ephemerality of a play performance and the more durable form of a printed play text - including its dedication - which could extend the life of plays and enhance the reputation of their authors.

The contents page of the 1675 edition of Machiavelli’s works - with the letter at the bottom. (EEBO).

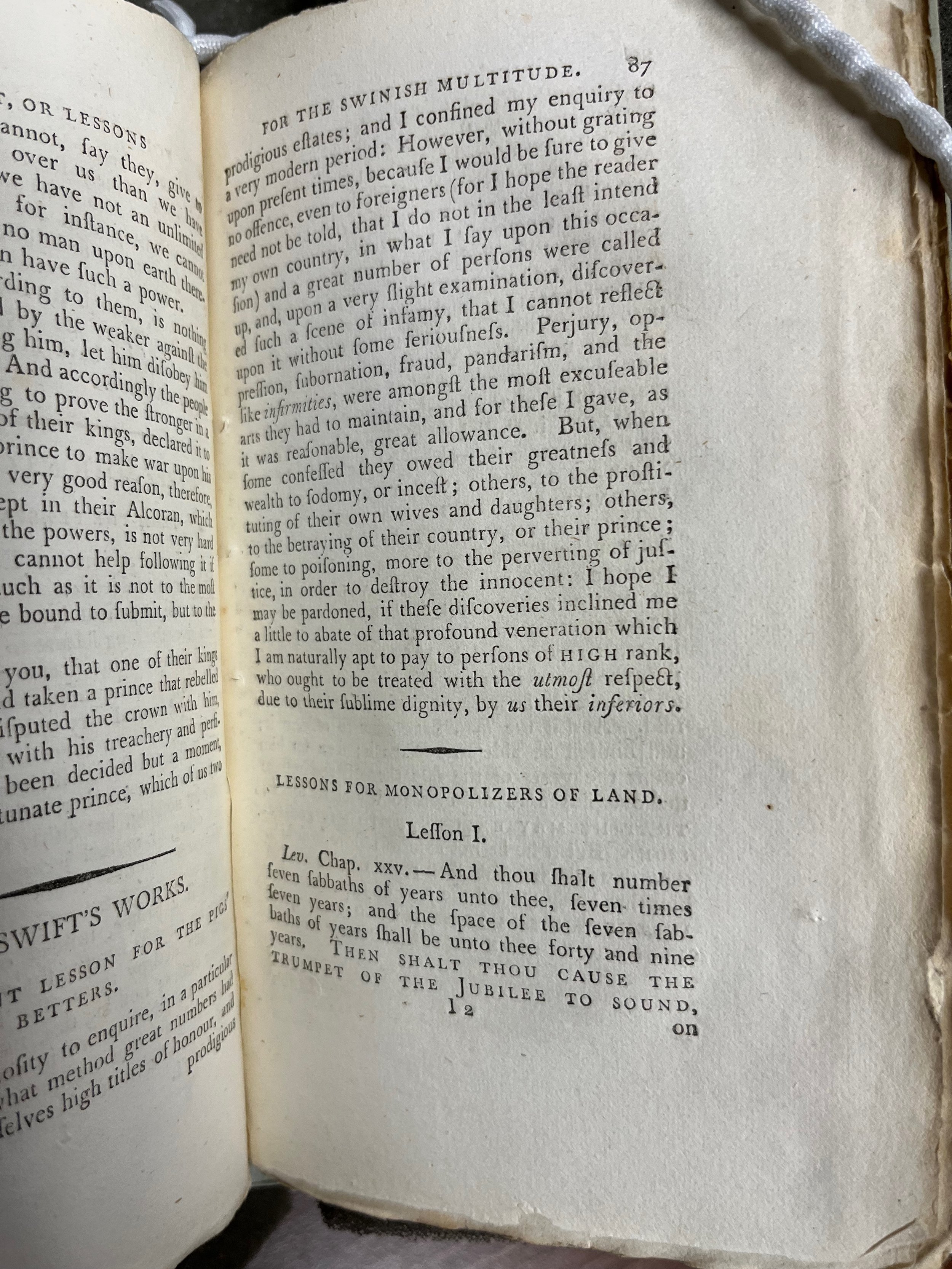

Closely related to the theme of longevity versus durability is that of visibility versus obscurity, and a number of papers also touched on the idea of hidden texts. This was again brought into focus by Katherine's paper on brass inscriptions. I was intrigued by the pro-monarchy sentiments that were inscribed inside bells produced in 1641 and 1650. Was this a case of communities expressing their sympathy and support for Charles I in a way that was safe, precisely because the words could not easily be read? Other papers explored the notion of hidden texts - or hidden ideas within texts - in different ways. This might be a matter of the positioning of a particular text within a volume. Charlotte McCallum noted that in the 1675 edition of Machiavelli's works the spoof letter from 'Machiavel' was placed at the end of the volume (a fact that was reflected on the contents page). In some later editions it appeared earlier in the volume, and in some a manuscript note was added drawing attention to the controversial nature of the ideas contained in the letter. The letter, then, was made more or less obscure through the materiality of the volume - its positioning within it and the addition or removal of other paratextual material. This reminded me of the practice within the Encyclopédie of hiding controversial topics in obscure places. The life and thought of the English republican James Harrington, for example, is discussed in the entry for Rutland; the English county with which the Harrington family was associated.

Papers by Marie-Louise Coulahan and Lizzie Scott-Baumann offered a gender dimension to this idea of hidden texts. Marie-Louise presented her RECIRC project to us. One of the findings of this project is that while women rarely wrote overtly political texts, that does not mean that they did not engage in politics. Rather they had to find suitable vehicles for doing so. Petitions (such as that of the Mariners' Wives and the Gentlewomen's Petition) and prophetic writings were often used to make political statements. Similarly, both Lucy Hutchinson and Margaret Cavendish wrote about their husbands as a way of expressing their own political views. It was noted too that correspondence by women is often undervalued as a political text. Where the correspondence of men is seen as important, that by women is often dismissed as mere 'gossip'. Lizzie took this notion of hidden ideas to a deeper level, exploring how the language used by Lucy Hutchinson and Anne Wharton in their poems addressed to Edmund Waller, served to subtly critique his behaviour and actions.

Image by Rachel Hammersley. Taken during the workshop with the Thin Ice Press.

Our workshop ended with us addressing the materiality of texts from a different direction. Helen Smith led a workshop with the Thin Ice Press. We were given the opportunity to type set a short sentence (which proved to be a very fiddly process) and then to print a poster of our own. This gave us all a new appreciation for the work done by early modern printers. It became apparent just what a monumental task printing a text was at that time, and it made the typographical errors that are common in early modern texts much more understandable. While I will continue to use resources such as EEBO and ECCO to read early modern texts, I left York knowing that the distance between my understanding and the practical realities of the production and consumption of early modern political texts had narrowed perceptibly as a result of the workshop.

Image by Rachel Hammersley. Taken during the workshop with the Thin Ice Press.