For personal reasons the commemoration of the dead, and the legacies they leave to those who remain, have been on my mind recently. Though inheritance is usually assumed to refer to money, I am much more interested in the ideas, practices, and values that the dead bequeath to the living. Thomas Hollis is a particularly interesting case when it comes to legacies of both kinds.

Thomas Hollis by Giovanni Battista Ciprani, etching 1767. National Portrait Gallery NPG D46108. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

In my last blogpost I referred to the donation of approximately 3,000 books that Hollis sent to Harvard College in Massachusetts. Partly in recognition of this, the catalogue of the current Harvard University Library is called HOLLIS - a reference to the donations provided by the family and a convenient acronym for Harvard Online Library Information System. Hollis was not the first of his family (nor even the first with his name) to make donations to Harvard. His great grandfather - also called Thomas Hollis - founded several posts at Harvard which still bear his name, and was commemorated in a hall on campus and a street in the area.

Like his great grandfather Hollis had no children. Yet instead of passing on his inheritance via different family lines, as previous generations had done, Hollis chose to leave his own substantial fortune to his friend Thomas Brand, who subsequently styled himself Thomas Brand Hollis in recognition of the legacy.

Thomas Brand was born in Essex around 1719 (Colin Bonwick, 'Hollis, Thomas Brand, c.1719-1804, radical.' Oxford Dictionary of National Biography). Being from a dissenting family he could not attend an English University and so studied at Glasgow where he was taught by the great Francis Hutcheson and became friends with Hollis's future collaborator Richard Baron. Brand and Hollis are said to have met at the inns of court in London in the 1740s. They travelled around Europe together in 1748-9.

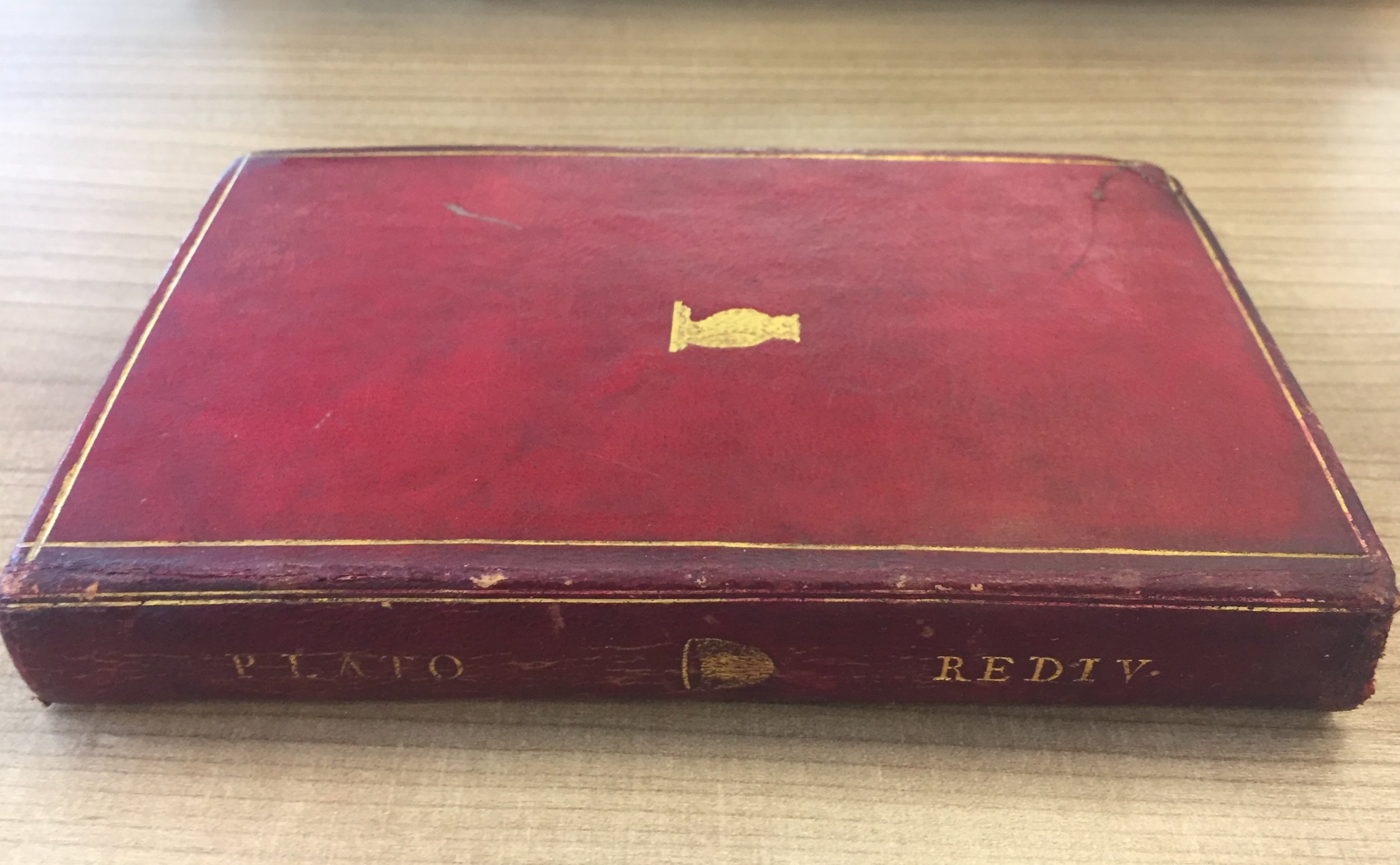

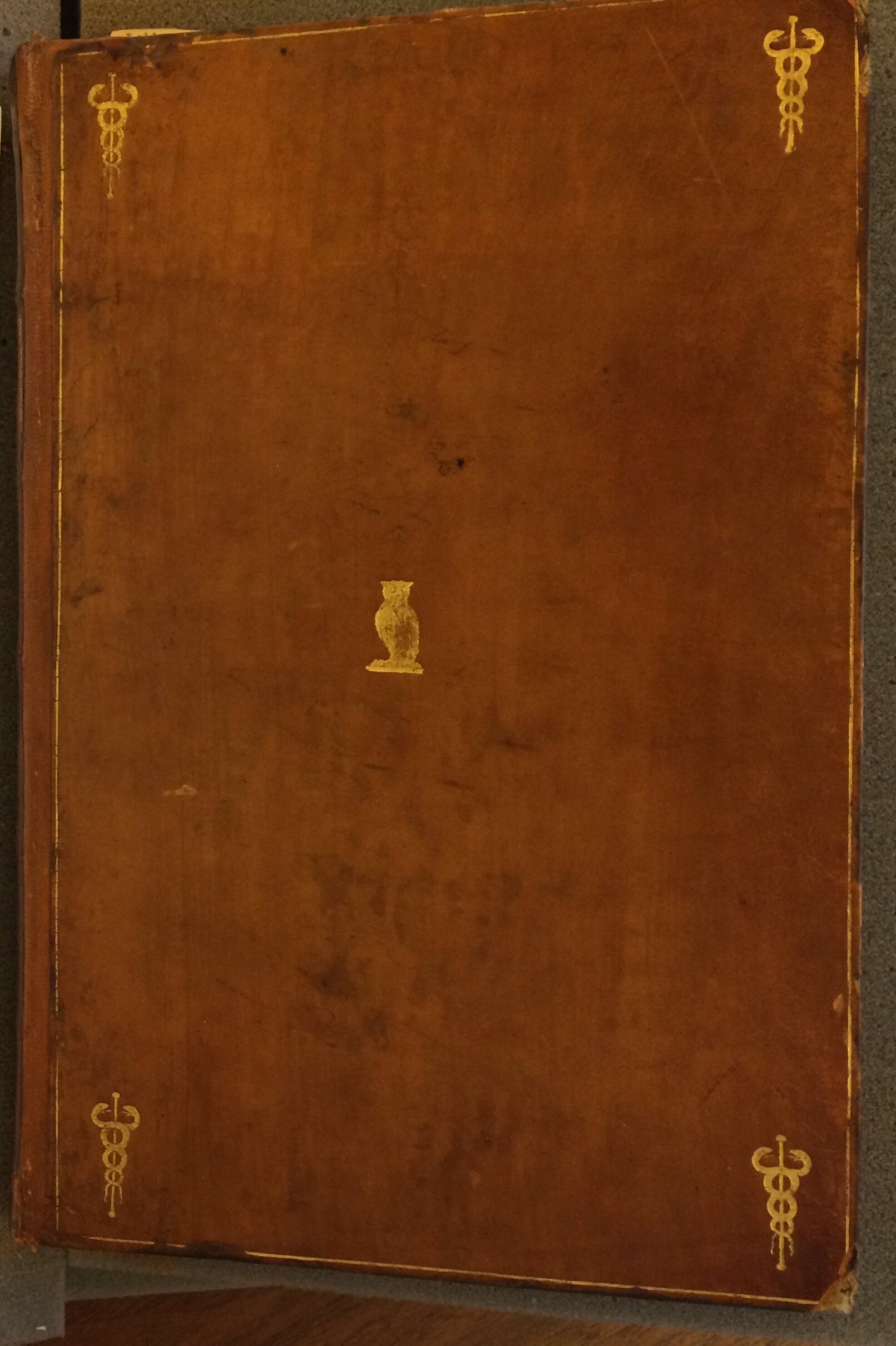

Hollis had always been keen to support Scottish institutions. In addition to the bequest in his will of books for Scottish University libraries, he also made donations to the Advocates Library in Edinburgh, including this copy of Henry Neville’s Plato Redivivus, or a dialogue concerning government (London, 1763). National Library of Scotland ([AD]7/1.8). It is reproduced here under a Creative Commons Licence with permission from the Library.

When Thomas Hollis died in 1774 Thomas Brand, whom Hollis described as 'my dear friend and fellow traveller', was named sole executor of his will and inherited his lands and the residue of his personal estate (The National Archives: PROB 11/994/68 'The Will of Thomas Hollis of Lincoln's Inn'). Hollis insisted on a private and modest funeral and, as was conventional, left small donations to the poor in the parishes near to his Dorset estate and money to various servants, family members, and friends, as well as to book binders, engravers, and printers with whom he had worked during his life. Hollis also continued his family's philanthropic traditions as well as those he had established during his lifetime. He pledged £300 to rebuild the almshouses that had been constructed by his great grandfather in Sheffield and £100 to the Society for Promoting Arts and Commerce in London. He also left money to be spent on books 'relating to Government or to civil or natural history or to ... Mathematics' for the university libraries at Edinburgh, Glasgow, Aberdeen, St Andrews and Dublin, as well as for the public library at Berne and the university library at Geneva, in addition to a larger donation for Harvard.

Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal), A View of Walton Bridge, 1754, oil on canvas, 48.7 x 76.4 cm, DPG600. Dulwich Picture Gallery, London. With thanks to curator Lucy West for her assistance. This painting was commissioned by Thomas Hollis. It depicts Hollis himself (in the yellow coat) and his friend Thomas Brand.

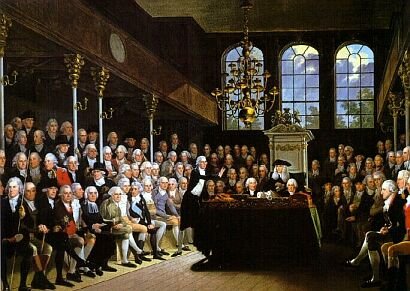

As well as enacting these bequests, Thomas Brand also advanced Hollis's legacy in other ways. The two men shared a dissenting background and a commitment to political radicalism and reform. Brand Hollis was a member of several reform societies including the Revolution Society established in 1788 and the Society for Constitutional Information (SCI). He was a founder member of the SCI attending its first meeting in April 1780, often chairing sessions, and being elected President in December of that year (The National Archives: TS 11/1133).

In its purpose and activities the SCI echoed and extended Hollis's campaign to disseminate political texts and share political information. Hollis had sent copies of a wide range of works to university and public libraries in many countries. As I noted in my last blogpost, he paid particular attention to North America where his donations were explicitly designed to influence how the colonists interpreted the actions of the British government against them. In short, Hollis appears to have been seeking to rouse the Harvard students to revolutionary action by providing them with specific reading material on the nature of their rights as Englishmen and the threats posed to those rights - and therefore to their liberty - by the actions of the British government towards them. The SCI also disseminated political texts for free, this time in England. Its aim in doing so was to promote and eventually bring about political reform. The terms in which this aim was expressed were very similar to those used by Hollis in relation to the American colonists:

As every Englishman has an equal inheritance in this Liberty; and in those Laws

and that Constitution which have been provided for its defence; it is therefore

necessary that every Englishman should know what the Constitution IS; when it is

SAFE; and when ENDANGERED (An address to the public, from the Society for

Constitutional Information. London, 1780, p. 1).

There was also a similarity in the particular texts thought worthy of dissemination. At a meeting on 12th May 1780, at which Brand Hollis was present, the Society resolved to task one of its members, Capel Lofft, to:

compile a Tract or Tracts, consisting of Extracts from the

Mirror of Justices, Fleta, Bracton, Fortesquieu, Selden, Bacon,

Sir Thomas Smith, Coke, Sidney, Milton, Harrington, Nevile,

Molesworth, Bolingbroke, Price, Priestly, Blackstone, Somers,

Davenant, the Essay on the English Constitution, and other Authors

as may clearly define, or describe in few Words the English

Constitution (The National Archives: TS 11/1133).

With just two exceptions (Sir Thomas Smith and Charles Davenant), works by all of these authors had been sent by Hollis to Harvard.

As well as disseminating the texts free of charge, both Hollis and the SCI used newspapers and periodicals to advertise them and their relevance to contemporary affairs. In April 1766 Hollis inserted the following advert into the London Chronicle to alert the Corsican rebels who were drawing up a new constitution for the island - and more especially their British supporters - of the potential a particular English republican text offered them in their endeavour.

TO THE PEOPLE OF CORSICA

FELICITY

"The Oceana of James Harrington, for practicable-

ness, equality and completeness, is the most perfect

model of a Commonwealth, that ever was delineated

by antient or modern pen (The London Chronicle, 10 April 1766).

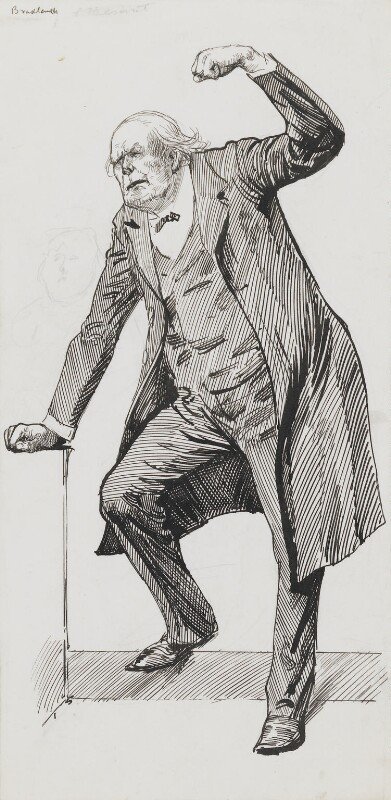

John Somers, Baron Somers by Sir Godfrey Kneller, Bt. c.1705. National Portrait Gallery NPG 490. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

In the same vein, from Spring 1782, members of the SCI began inserting extracts from key texts into the General Advertiser. These included extracts selected by Brand Hollis from a work by John Somers, first Baron Somers (1651-1716), a notable Whig and one time Lord Chancellor. The extracts, which appeared in the General Advertiser on Monday 18 March 1782, concerned the limits of the ruler's powers and the rights of the people. Somers argued that a sovereign who invades or subverts the fundamental laws of society gives up his legal right to govern and absolves his subjects of obedience. Citing the popular phrase asserting the rights of the people salus populi, he claimed that all law and government is aimed at the public good and therefore: 'A just Governor, for the benefit of the people, is more careful of the public good and welfare, than of his own private advantage.' 'He who makes himself above all law, is no Member of a Commonwealth, but a mere tyrant whenever he pleases' and under such a magistrate the people would be justified in exercising a right of resistance. Though probably originally written in the context of the Glorious Revolution, these sentiments were meaningful to those engaged in the reform campaign and perhaps designed as a warning to George III.

There is one final more frivolous way in which Brand Hollis continued his friend's legacy. Hollis had had a curious habit of naming fields and farms on his Dorset estate at Corscombe and Halstock after thinkers, works, and places he respected. In July 1773 Hollis noted in a letter that he had named a small farm on his estate after George Buchanan 'this oldest son of liberty' (Caroline Robbins, 'Thomas Hollis in His Dorsetshire Retirement' in Absolute Liberty, ed. Barbara Taft. 1982, p. 240). Another farm of 247 acres was named after James Harrington and on that farm was a field he called Oceana after Harrington's most famous work. To the west of Harrington Farm was another called Milton Farm after John Milton, which included a field named after John Toland - who had edited both Milton's and Harrington's works. Also in the vicinity were farms named for other leading English republicans: Algernon Sidney, Edmund Ludlow, and Henry Neville.

Dorset History Centre, D1_MO_3 Plan of Harrington Farm from the Corscombe Estate Map. With thanks to the Dorset History Centre for assistance and permission.

We know that Brand Hollis was aware of Hollis's actions in this regard since a survey of the estate that Brand Hollis conducted in 1799, now held at Dorset History Centre, details the names of the various farms and fields.

Brand Hollis not only maintained and memorialised Hollis's nomenclature on his Dorset estate, he also engaged in the same practice himself - naming trees on his property at Hyde in Essex after George Washington and other heroes of the American Revolution (Bonwick, ODNB). To my mind, legacies of place names, book collections, and the values of kindness and generosity, are far more meaningful and enduring than any financial bequest - even from someone with as extensive a fortune as Thomas Hollis.